3 December 2023

This week brought the sad news about Charlie Munger, a teacher to many past and future generations of investors. There are many lessons to draw from his investment and life. Luckily, there was more than one book written, many shareholder letters available (some stored in this Library and many hours of interviews recorded.

Becky Quick spoke to Charlie just two weeks before his death. It was a great interview. The following comments from Charlie resonated in my mind:

Becky Quick spoke to Charlie just two weeks before his death. It was a great interview. The following comments from Charlie resonated in my mind:

CHARLIE MUNGER: Everybody struggles. The iron rule of life is everybody struggles.

BECKY QUICK: I try and think back of what the toughest moments might’ve been and how you got through some of those. And, I mean--

CHARLIE MUNGER: Well, we all know how to get through them. The great philosophers of realism are also the great philosophers of what I call soldiering through. If you soldier through, you can get through almost anything. And it’s your only option. You can’t bring back the dead, you can’t cure the dying child. You can’t do all kinds of things. You have to soldier through it. You just somehow soldier through. If you have to walk through the streets, crying for a few hours a day as part of the soldiering, go ahead and cry away. But you can’t quit. You can cry all right, but you can’t quit.

I purchased my ticket to Omaha last summer. I still look forward to the trip in May 2024. Sadly, the Berkshire meeting will never be the same fun...

Two weeks ago, I wrote about how such a dull and slow-growth sector as insurance gave rise to several successful compounders. Previously, I also wrote about investing in oil & gas, other commodities and technology.

This time, I will share my thoughts about investing in banks. I hope this will introduce new perspectives in your analysis and improve your investment process further.

This time, I will share my thoughts about investing in banks. I hope this will introduce new perspectives in your analysis and improve your investment process further.

My first bank stock

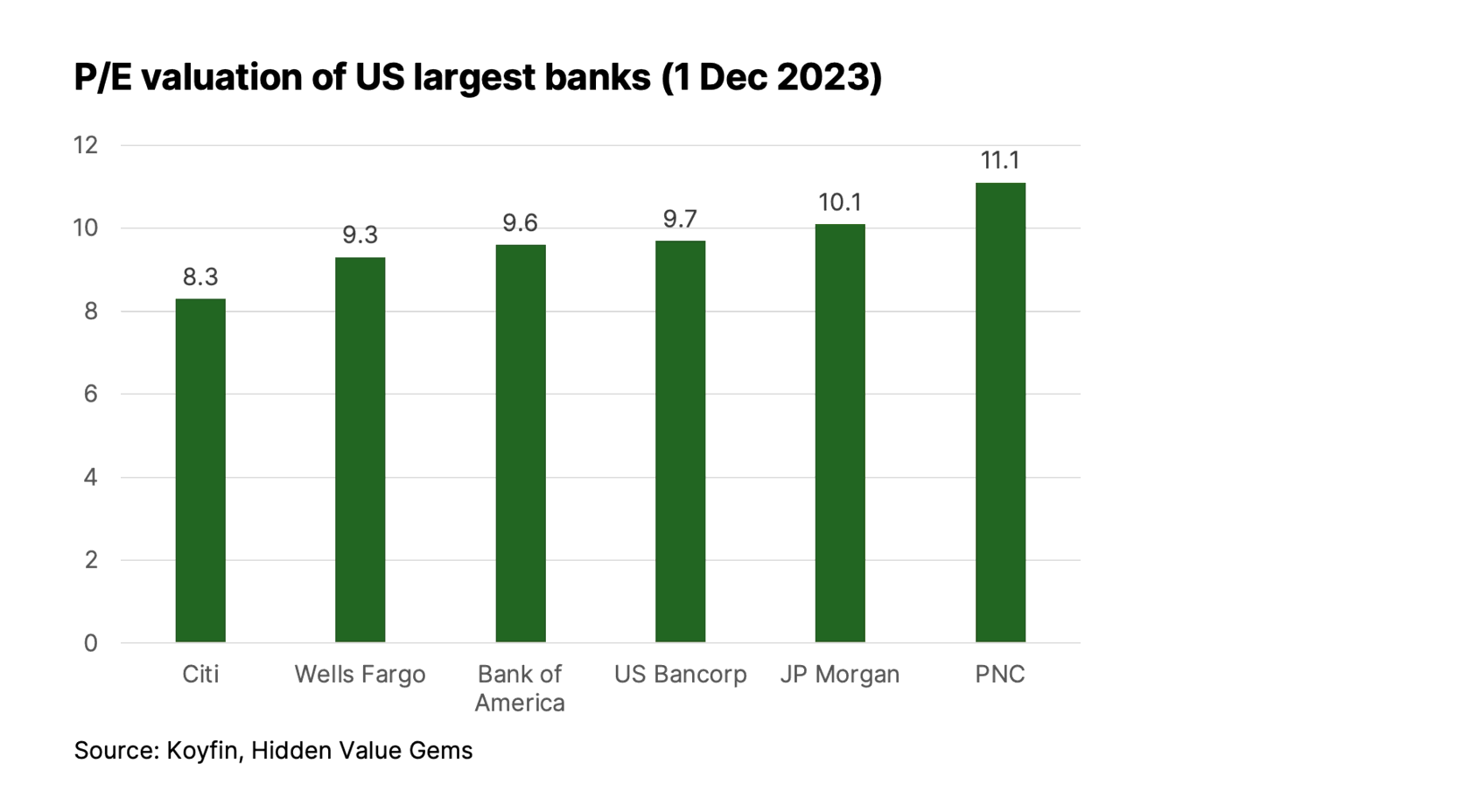

Banks are popping up at the top of almost every value screen you run today, regardless of the geography. A single P/E bank stock is no longer exclusive to Emerging Markets, as was the case in the past. Even in the best-performing and traditionally pricy U.S. market, banks are frequently valued below a 10x P/E ratio.

So, is this a multi-year opportunity to take advantage of the market pessimism? Are banks benefiting from the rising rates, or are they suffering from the asset-liability mismatch like SVB?

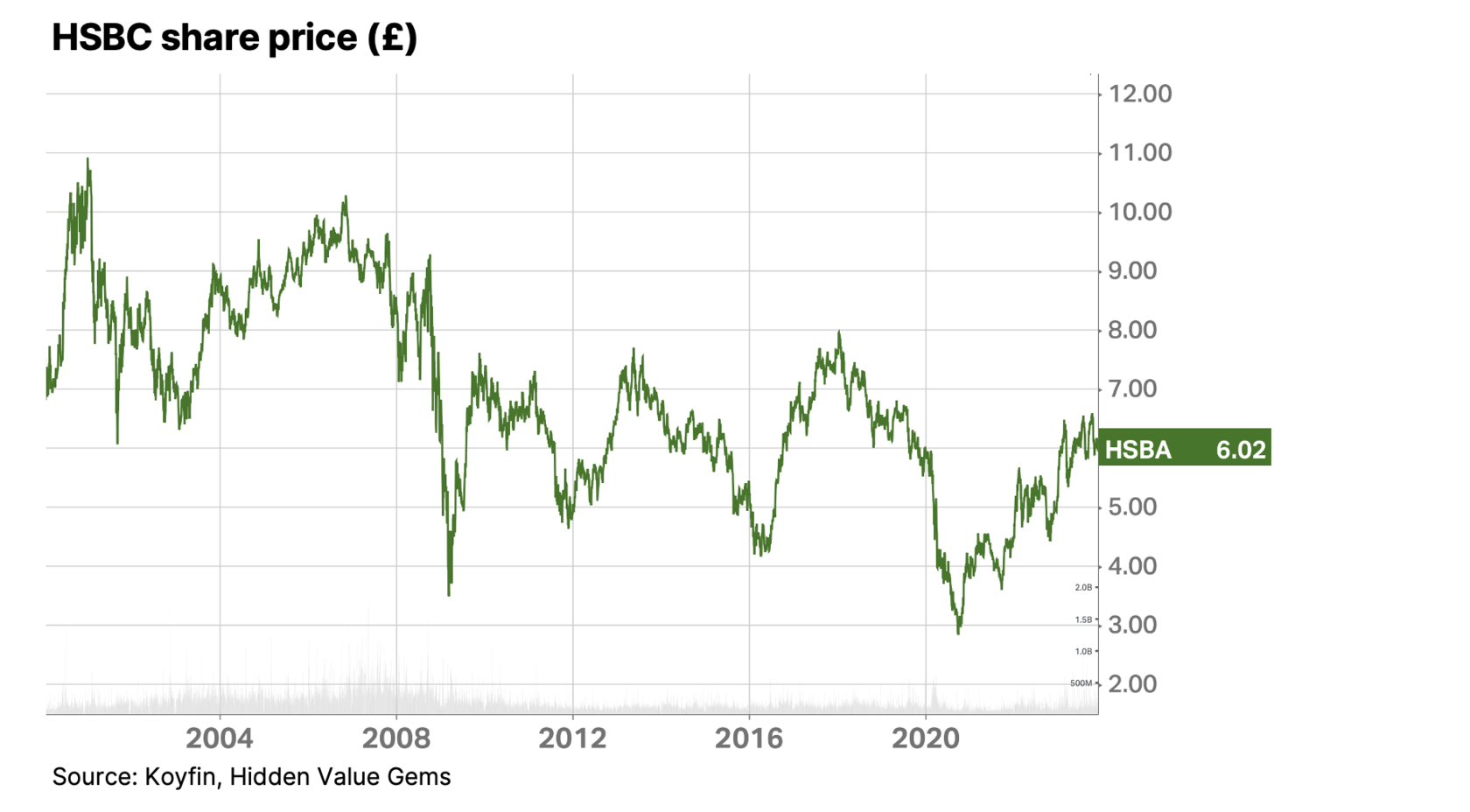

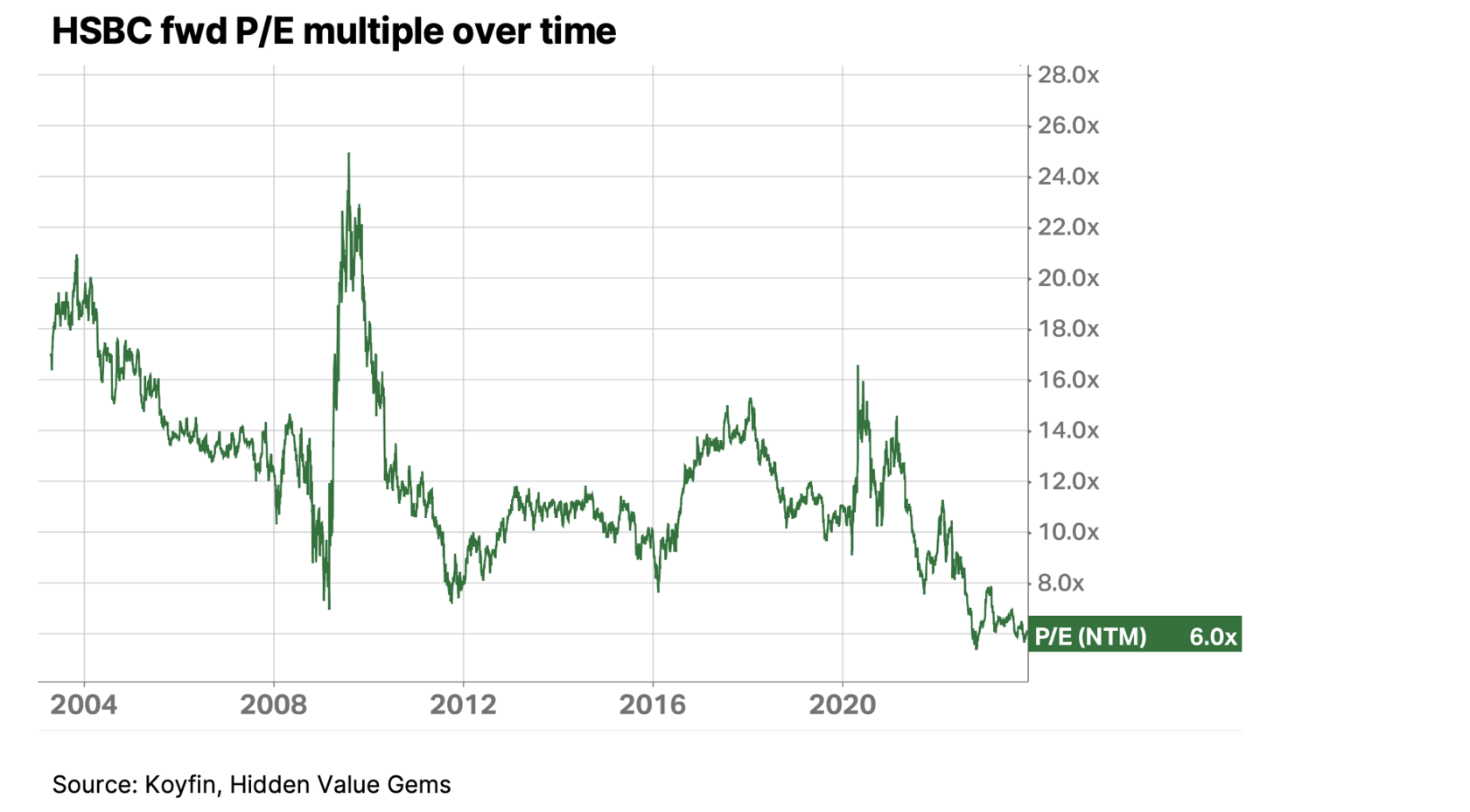

I bought my first bank stock in 2007. Having just read Graham’s Intelligent Investor, I started looking for businesses with wide moats selling at attractive prices. The first UK banking account that I opened was with HSBC. It had probably the largest branch network at that time; its ads were the first thing you saw when you landed at Heathrow, and it had over 100 years of history and a large international presence. And it was selling for just over 10x P/E, cheaper than the market. What not to like?

Well, here is how the stock performed afterwards.

Its earnings barely increased while its valuation (P/E multiple) halved.

Luckily, I sold the stock in 2010 for about 600p, the same price it is trading today after 13 years.

I bought my first bank stock in 2007. Having just read Graham’s Intelligent Investor, I started looking for businesses with wide moats selling at attractive prices. The first UK banking account that I opened was with HSBC. It had probably the largest branch network at that time; its ads were the first thing you saw when you landed at Heathrow, and it had over 100 years of history and a large international presence. And it was selling for just over 10x P/E, cheaper than the market. What not to like?

Well, here is how the stock performed afterwards.

Its earnings barely increased while its valuation (P/E multiple) halved.

Luckily, I sold the stock in 2010 for about 600p, the same price it is trading today after 13 years.

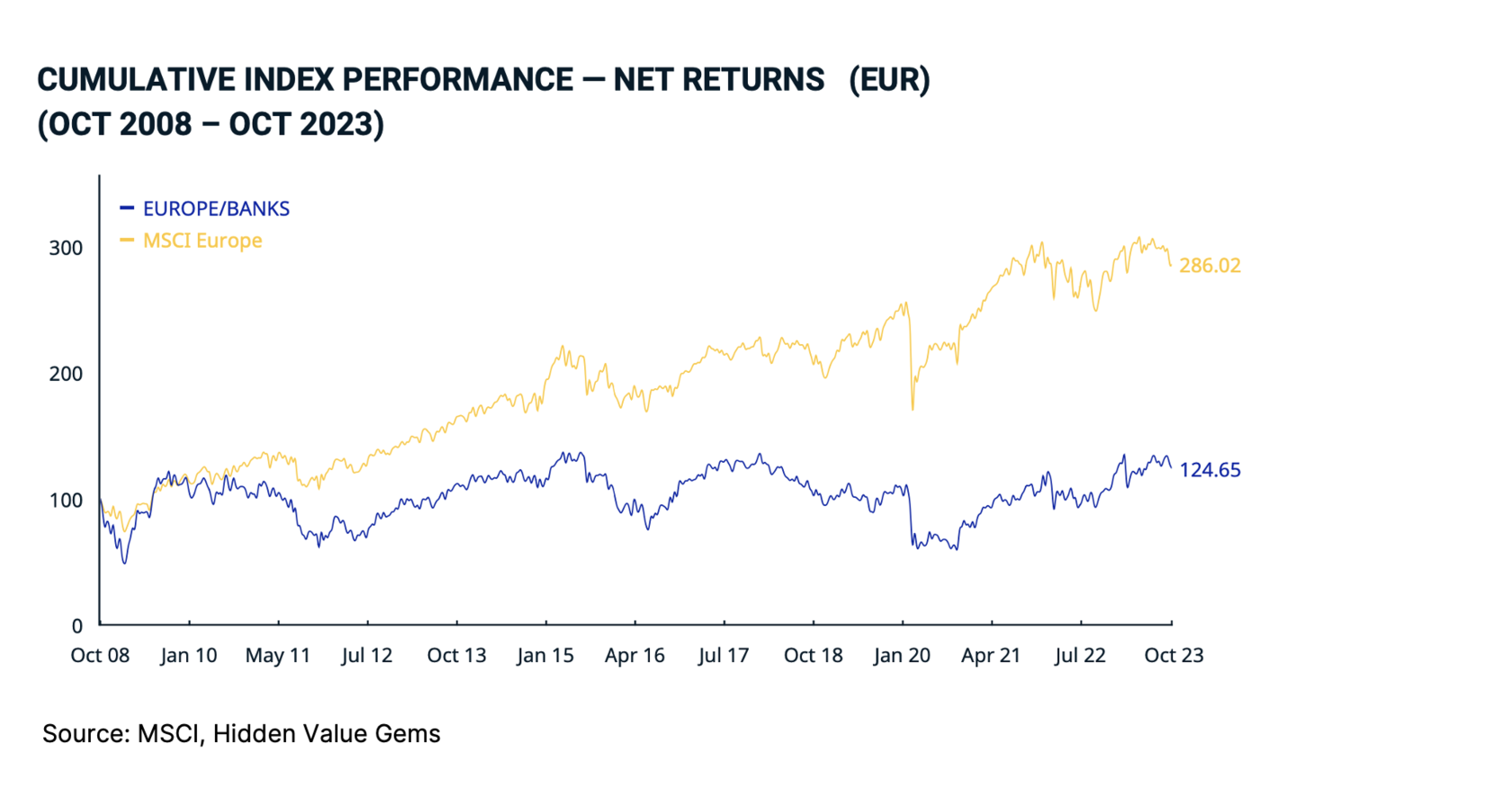

It was more than just a poor choice of an individual stock. The whole group of European banks have severely underperformed the market.

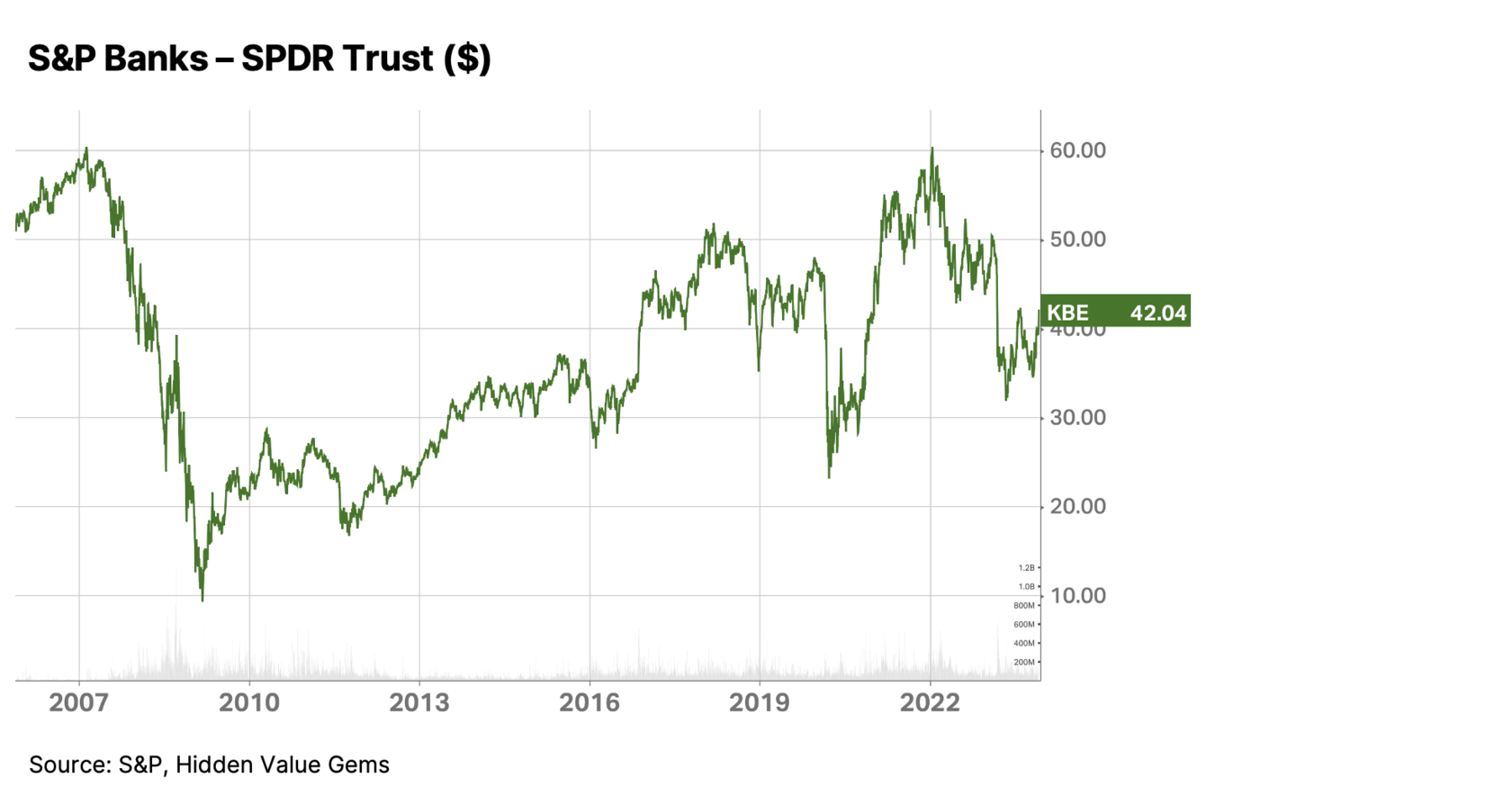

US banks performed just a little better.

I have since owned just one other bank (in EM) for a relatively short period of time.

Of course, calling banks uninvestable today just based on this experience is wrong. But there are some lessons to be learnt from this. Here is what I have discovered about banks since then.

Of course, calling banks uninvestable today just based on this experience is wrong. But there are some lessons to be learnt from this. Here is what I have discovered about banks since then.

Bank’s business model

Commercial banks have two primary business functions:

Consequently, the two sources of the bank’s revenue are interest income and fees.

The two main costs associated with these service lines are borrowing costs and business expenses related to IT, infrastructure, compliance and regulations.

Net interest margin is the spread between a yield earned on the bank’s assets and its cost of funding.

The two streams are quite different in terms of cyclicality. Interest income correlates highly with the economic cycle, while fees are more stable.

- Accept deposits (hold clients’ money) and redirect them to businesses via loans.

- Provide money-related services (e.g. transfers).

Consequently, the two sources of the bank’s revenue are interest income and fees.

The two main costs associated with these service lines are borrowing costs and business expenses related to IT, infrastructure, compliance and regulations.

Net interest margin is the spread between a yield earned on the bank’s assets and its cost of funding.

The two streams are quite different in terms of cyclicality. Interest income correlates highly with the economic cycle, while fees are more stable.

How strong is the bank’s moat?

The bank’s size used to be an essential source of competitive advantage. Customers would find it convenient when they could quickly fix their issue at a bank’s branch. However, in today’s digital world, a branchless bank model is quite common. Banks often compete on the quality of their app rather than the size of their branch networks.

When a customer opened an account with a bank, it used to be the beginning of a new business relationship.

Some investors like to point out that customers rarely change banks. Some even say an adult is more likely to divorce than switch to another bank.

When a customer opened an account with a bank, it used to be the beginning of a new business relationship.

Some investors like to point out that customers rarely change banks. Some even say an adult is more likely to divorce than switch to another bank.

“It’s very difficult to change bank accounts. People do it every 26 years. You’re more likely to be divorced than to change your bank account, and that’s partly because it’s difficult.”

- Ed Balls, Shadow chancellor (2012)

With more transparency, thanks to digital technologies, the bank with the highest rate can win more savings deposits. Customers don’t have to worry too much about the bank’s reputation if they know the government guarantees their deposits.

And while banks may be happy that their customer numbers do not fall, it may not mean that their cash balances remain stable.

The level of competition has been on the rise. In retail banking, there are many digital challengers. In commercial banking, alternative capital providers gain market share, too. These include Private Equity and Hedge Funds, Sovereign wealth funds, and Commodity traders. Besides, issues such as ESG force banks to retreat from specific sectors.

And while banks may be happy that their customer numbers do not fall, it may not mean that their cash balances remain stable.

The level of competition has been on the rise. In retail banking, there are many digital challengers. In commercial banking, alternative capital providers gain market share, too. These include Private Equity and Hedge Funds, Sovereign wealth funds, and Commodity traders. Besides, issues such as ESG force banks to retreat from specific sectors.

Banks = Utilities?

Banks play a critical role in our society, but does this help them charge premium prices for their services? To me, there is not much difference between an electric utility and a bank. Both facilitate the life of a modern society, but neither seems to win customers’ loyalty. I call a bank when I have to, often when something goes wrong, not because I want to. My experience is entirely different when I am switching between apps on my iPhone or using Amazon to order a new item or watch Amazon Prime.

I rarely see people delighted by banking services, especially by more traditional banks. Great businesses, on the other hand, often focus on keeping the customer happy by providing the best service. This relationship allowed them not only to win more customers but also to launch complementary products and eventually expand into new business segments. Amazon is the best example of this approach.

I wonder why my experience dealing with a bank is usually between “all right” and “disappointing”? Just like with utility. On the other hand, I am almost excited when I unpack a new Apple product.

Banks may try to delight you with cashback or other bonuses, but they come from the fees they earn from merchants when you spend the money. And every bank makes these fees - so their ability to offer you better rewards is limited. There is little reason to stay loyal to one bank, especially today when switching has become much easier.

I read recently that between 2012 and 2022, the number of bank branches in the UK fell by 40%. According to the FCA, the Big Four banks’ market share in personal accounts (Lloyds, HSBC, Barclays and NatWest) fell from 68% in 2018 to 64% in 2021. Those taking the biggest bites have been new online-only banks such as Monzo and Starling. These digital challengers had a market share of 1% in 2018 but one of 8% by 2021.

The Current Account Switching Service handled 1.3m British customers in H1 ’23, a rise of 50% compared to last year.

The data may differ from country to country, but the core idea remains the same. Customers go for the best terms, not the brand, as banks offer very similar products. Large banks, in particular, are slow to adapt to improve their service, at least from my experience.

I rarely see people delighted by banking services, especially by more traditional banks. Great businesses, on the other hand, often focus on keeping the customer happy by providing the best service. This relationship allowed them not only to win more customers but also to launch complementary products and eventually expand into new business segments. Amazon is the best example of this approach.

I wonder why my experience dealing with a bank is usually between “all right” and “disappointing”? Just like with utility. On the other hand, I am almost excited when I unpack a new Apple product.

Banks may try to delight you with cashback or other bonuses, but they come from the fees they earn from merchants when you spend the money. And every bank makes these fees - so their ability to offer you better rewards is limited. There is little reason to stay loyal to one bank, especially today when switching has become much easier.

I read recently that between 2012 and 2022, the number of bank branches in the UK fell by 40%. According to the FCA, the Big Four banks’ market share in personal accounts (Lloyds, HSBC, Barclays and NatWest) fell from 68% in 2018 to 64% in 2021. Those taking the biggest bites have been new online-only banks such as Monzo and Starling. These digital challengers had a market share of 1% in 2018 but one of 8% by 2021.

The Current Account Switching Service handled 1.3m British customers in H1 ’23, a rise of 50% compared to last year.

The data may differ from country to country, but the core idea remains the same. Customers go for the best terms, not the brand, as banks offer very similar products. Large banks, in particular, are slow to adapt to improve their service, at least from my experience.

Regulations

If banks have more in common with utilities, then they should be equally dependent on government regulation. In fact, the regulatory regime for banks is much more onerous than for utilities. Not only do they have to comply with various capital ratios, but they also face a long list of anti-money laundering regulations, financial sanctions and other restrictions.

Banks are forced to prioritise compliance over profitability. That may be fine, but the consequences of not complying are so high that banks often only accept customers if they take a chance of facing regulatory enquiries later.

Extra checks banks carry out when a customer makes a payment or receives money reduce customer satisfaction further.

Banking services often become a forced necessity rather than a pleasant experience.

The government’s approach to banks is similar to social goods, not private enterprises. The Global Financial Crises empowered states to make critical decisions and ultimately decide on the appropriate level of profitability. Take, for example, windfall taxes on banks introduced by various European countries in 2022. Or consider the recent proposal made in the UK to require banks to provide cash services to customers within 3 miles.

Banks are forced to prioritise compliance over profitability. That may be fine, but the consequences of not complying are so high that banks often only accept customers if they take a chance of facing regulatory enquiries later.

Extra checks banks carry out when a customer makes a payment or receives money reduce customer satisfaction further.

Banking services often become a forced necessity rather than a pleasant experience.

The government’s approach to banks is similar to social goods, not private enterprises. The Global Financial Crises empowered states to make critical decisions and ultimately decide on the appropriate level of profitability. Take, for example, windfall taxes on banks introduced by various European countries in 2022. Or consider the recent proposal made in the UK to require banks to provide cash services to customers within 3 miles.

The silver lining from the regulatory burden is that it can add a hassle to opening an account, which means that customers may decide to stay with the same institution even if they are not fully satisfied.

Regulations can also curb competition as capital requirements or other restrictions create barriers for new entrants.

Regulations can also curb competition as capital requirements or other restrictions create barriers for new entrants.

Limited pricing power and sensitivity to macro

Like commodities, banking profitability is primarily determined by external factors (Central Bank’s rates, inflation, economic growth). Banks have little power to change their profitability since the yields available on investments, as well as the costs of borrowing, are usually set by the market.

They are also impacted by the state of the economy. During the recession, the share of customers that fail to meet their loan payments rises which hits banking sector profits.

Since banks struggle to stand out, they are not able to grow market share significantly. Hence, their long-term growth potential is capped by GDP. They are more stalwarts to borrow from Peter Lynch than multi baggers.

They are also impacted by the state of the economy. During the recession, the share of customers that fail to meet their loan payments rises which hits banking sector profits.

Since banks struggle to stand out, they are not able to grow market share significantly. Hence, their long-term growth potential is capped by GDP. They are more stalwarts to borrow from Peter Lynch than multi baggers.

Inherent fragility

Banks can appear safe and operate profitably for many years before a single problem wipes out their capital one day. It doesn’t happen with every bank, of course, but even the best institutions can experience the stress that materially impairs their earning power.

The reason for this lies in the permanent asset-liability mismatch. Banks receive short-term deposits, which they transform into longer-term loans. Various instruments and smart risk management can allow the bank to minimise the consequences of such a mismatch, but they cannot eliminate them completely.

Banks also depend on the external environment as market rates drive the value of their assets. Banks take the loss if rates go up, and they must sell some of their assets before maturity. Since banks’ assets are 10-20 times larger than their capital, a slight drop in asset values could be enough to wipe out their equity.

Banks may need to sell certain assets prematurely if they experience liquidity problems (when too many depositors want to take their money from the bank simultaneously). What makes it worse is that a particular bank can be in excellent condition, but a problem at another bank with a bad culture can cast doubts on all banks in a country.

This inherent fragility (asset-liability mismatch and high leverage) exposes banks to falling share prices more. Generally, a lower share price can be good news for long-term shareholders as the company can take advantage of poor sentiment and buy back its shares, increasing its value per share. For a bank, a falling share price may signal more profound problems. Banks usually reduce distributions and buybacks during a downturn to preserve their capital.

The reason for this lies in the permanent asset-liability mismatch. Banks receive short-term deposits, which they transform into longer-term loans. Various instruments and smart risk management can allow the bank to minimise the consequences of such a mismatch, but they cannot eliminate them completely.

Banks also depend on the external environment as market rates drive the value of their assets. Banks take the loss if rates go up, and they must sell some of their assets before maturity. Since banks’ assets are 10-20 times larger than their capital, a slight drop in asset values could be enough to wipe out their equity.

Banks may need to sell certain assets prematurely if they experience liquidity problems (when too many depositors want to take their money from the bank simultaneously). What makes it worse is that a particular bank can be in excellent condition, but a problem at another bank with a bad culture can cast doubts on all banks in a country.

This inherent fragility (asset-liability mismatch and high leverage) exposes banks to falling share prices more. Generally, a lower share price can be good news for long-term shareholders as the company can take advantage of poor sentiment and buy back its shares, increasing its value per share. For a bank, a falling share price may signal more profound problems. Banks usually reduce distributions and buybacks during a downturn to preserve their capital.

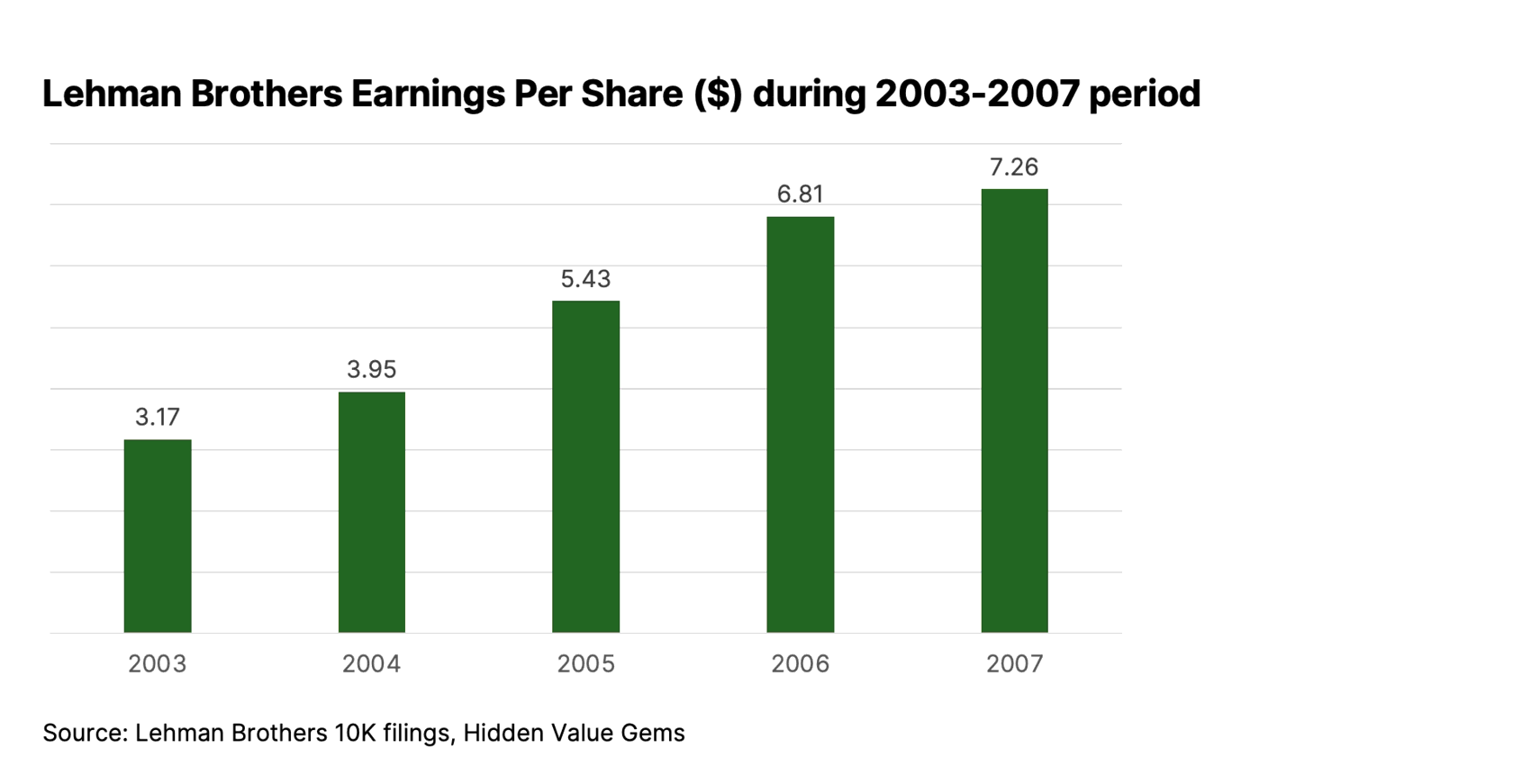

This role of confidence and reputation makes me uncomfortable to invest in banks as I find it hard to analyse. It is there until it is not. Of course, many problems at banks are self-inflicted, but not all. Here is a chart of Lehman Brothers’ EPS - a steady growth until one year…

Little analytical edge

The Lehman Brothers chart also shows that analysing financial institutions is challenging. One line in one segment of the financial statement may mean nothing. Part of the problem is banks’ inherent fragility, which I have already talked about.

Another issue is management’s discretion when preparing financial reports. Certain items require management to make their own estimates and judgements. This is a subjective activity by default, even if they use sophisticated models as part of the process.

Such items can be critical in estimating the bank’s profitability and leverage (e.g. credit losses, risk weights for capital ratios).

Besides, I am always uncomfortable about the fact that I need to know who the bank has provided loans to and what other assets it holds on the balance sheet. Aggregate numbers are available, with some additional details such as the loan book’s sector exposure or distribution of customers by size. But this does not say anything about whether a particular loan will be repaid or not.

In the case of a traditional consumer goods company, for example, I don’t have to worry about who bought the company’s product. I would like to know the core customer base and why they want a specific product, but it is a different question. This is more about the future upside rather than the existing downside risks.

In banking, you do not know your final profitability long after you have sold your product (provided a loan), which is entirely different to more traditional sectors.

Another issue is management’s discretion when preparing financial reports. Certain items require management to make their own estimates and judgements. This is a subjective activity by default, even if they use sophisticated models as part of the process.

Such items can be critical in estimating the bank’s profitability and leverage (e.g. credit losses, risk weights for capital ratios).

Besides, I am always uncomfortable about the fact that I need to know who the bank has provided loans to and what other assets it holds on the balance sheet. Aggregate numbers are available, with some additional details such as the loan book’s sector exposure or distribution of customers by size. But this does not say anything about whether a particular loan will be repaid or not.

In the case of a traditional consumer goods company, for example, I don’t have to worry about who bought the company’s product. I would like to know the core customer base and why they want a specific product, but it is a different question. This is more about the future upside rather than the existing downside risks.

In banking, you do not know your final profitability long after you have sold your product (provided a loan), which is entirely different to more traditional sectors.

Culture and incentives

One other negative aspect of banks, from my experience at least, is their culture. Often, employees are either encouraged to seek short-term profits at the expense of the long-term sustainability of the business or, on the other hand, are incentivised to reject most new businesses to avoid potential issues.

Employees can significantly impact investment banking and trading, demanding high bonuses when things go well and then getting large redundancy packages during a crisis.

The payoff often seems to favour employees rather than shareholders.

A friend recommended the book ‘A Blueprint For Better Banking: Svenska Handelsbanken and a Proven Model for More Stable and Profitable Banking’, which I read a few years ago. It emphasises the importance of incentives and a culture focused on long-term thinking.

Employees can significantly impact investment banking and trading, demanding high bonuses when things go well and then getting large redundancy packages during a crisis.

The payoff often seems to favour employees rather than shareholders.

A friend recommended the book ‘A Blueprint For Better Banking: Svenska Handelsbanken and a Proven Model for More Stable and Profitable Banking’, which I read a few years ago. It emphasises the importance of incentives and a culture focused on long-term thinking.

It was an interesting read. However, even a bank with such an outstanding management culture has not delivered exciting results for its shareholders, especially on a relative basis.

Key differences between Banking and Insurance

Banks and Insurance companies have a lot in common. Both sectors receive money upfront and do not know their ultimate profits long after selling a product. Such a model encourages long-term thinking and rewards businesses with the proper incentive structure and corporate culture.

Yet, there are a few critical differences.

Yet, there are a few critical differences.

- Banks are dealing with costs “given” to them by the market. If the risk-free rate in the economy is 5%, banks will not be able to attract term deposits at 2%. In insurance, the cost of the float becomes known over time and varies depending on how well the company runs its underwriting operations. The cost of insurance float is the “underwriting loss”, the amount of claims relative to the overall premiums collected. If the company sells 1,000 insurance policies and none of its clients make a claim, its cost of float is zero.

- Insurance companies are not prone to bank runs. Insurance companies rarely go under because of the public’s lost confidence.

- Banks suffer more from asset-liability mismatch.

- Regulation has a much more significant impact on the banking sector. There is no Central Bank for insurance companies.

- There are many more opportunities for skill to achieve different results in insurance. Due to heavy regulations and weaker moats, banks are more commoditised.

- Banks are much more sensitive to the macro environment than insurance companies. Insurance policies are often mandatory or critical for businesses (Director's insurance), and demand for such policies is more stable than demand for consumer credit or mortgages.

Conclusion: is Banking uninvestable?

As a value investor, I will never call any sector ‘uninvestable’.

There are interesting investment opportunities in the banking sector, just like in others. And they are not driven by price alone.

A bank with a niche focus has better chances of building long-term customer relationships and selling more products at better prices over time. Banks in certain regions can benefit from unique industry conditions (like regulation or level of competition).

Kaspi in Kazakhstan has proven to be a great business.

But there are a few pitfalls, and just chasing the price can be the wrong strong strategy. Buying a banking index today is a call on a one-time revaluation of their shares. It will generate short-term capital gains tax if you are right. But to be correct, you have to be sure that current earnings are sustainable and not driven by a unique combination of macro factors.

Even safe banks with large franchises and cost advantages can bring some negative surprises. Just look at Wells Fargo.

Finally, because banks are so interrelated with the overall macro picture, holding a bank’s stock would force me to pay more attention to macro commentary and forecasts. Not only are they often wrong, but such activity narrows your investment horizon and makes you more risk-averse than necessary. If you are constantly worried, you will never buy a single share.

So, sixteen years after purchasing my first bank stock, I am not overly excited about the banking sector and generally prefer to look for opportunities elsewhere. I am much more comfortable to hold several insurance conglomerates than banks.

There are interesting investment opportunities in the banking sector, just like in others. And they are not driven by price alone.

A bank with a niche focus has better chances of building long-term customer relationships and selling more products at better prices over time. Banks in certain regions can benefit from unique industry conditions (like regulation or level of competition).

Kaspi in Kazakhstan has proven to be a great business.

But there are a few pitfalls, and just chasing the price can be the wrong strong strategy. Buying a banking index today is a call on a one-time revaluation of their shares. It will generate short-term capital gains tax if you are right. But to be correct, you have to be sure that current earnings are sustainable and not driven by a unique combination of macro factors.

Even safe banks with large franchises and cost advantages can bring some negative surprises. Just look at Wells Fargo.

Finally, because banks are so interrelated with the overall macro picture, holding a bank’s stock would force me to pay more attention to macro commentary and forecasts. Not only are they often wrong, but such activity narrows your investment horizon and makes you more risk-averse than necessary. If you are constantly worried, you will never buy a single share.

So, sixteen years after purchasing my first bank stock, I am not overly excited about the banking sector and generally prefer to look for opportunities elsewhere. I am much more comfortable to hold several insurance conglomerates than banks.