We can be discussing new stock ideas in our pursuit of financial freedom, but could it be just the same as rowing in a leaking boat? And even if the boat is not rowing, how about we take a motorboat to arrive at our destination faster? Are we actually sure about the destination and navigation equipment? Do we have enough supply of freshwater before we go on a long journey?

There are many questions one has to think about apart from the technique of rowing and the physical power it takes if you need to cross the sea.

I think it is similar to investing. As I mentioned in my previous article, stock selection is only half of the success (and maybe even less), while good financial habits are responsible for the rest. For example, if you save regularly and add to your stock portfolio, if you do not try to guess the next market move, if you buy only stocks in businesses that you really understand (or just hold a broad market instead), if you avoid extreme leverage including on a personal level so that you can withstand adverse market developments and not sell during the time of panic - all these and other habits can take you further than just exceptional stock selection.

Over the past few months, I have been thinking more and more about the skill of making decisions. I have already written an article about general decision making in life. But I think a more practical skill of decision making in investing is crucial for success. I spent the first 20 years of my education in financial markets learning practical tools (valuation and financial analysis), learning about sectors (competitive advantages, business economics and key drivers) and learning general principles (‘stock is a share of a business’, ‘margin of safety’, ‘risk is not volatility’, ‘looking for alignment of interests such as owner/operator’ and so on).

However, I have realised that while there is still a lot to learn about new businesses and valuation, what is equally crucial is learning how to make decisions.

The reality is that, unfortunately, you can apply your valuation tools and have a clear view on the company’s valuation only in a perfect world, the world where you know all necessary information. And this perfect world also needs to be constant, because if a company you are analysing changes the quality of its product or enters new non-core business segments - then its value (measured as the sum of future cashflows discounted to present) would also change. Even if the company does not change, but consumer tastes evolve, or competitors become stronger, or regulation change - then the amount of cash the company is able to generate in the future would also change, and your original valuation would not hold.

And here is the key question - how do you update your view when new information comes in?

Basically, we need to act in a world of incomplete information and where events can unfold due to pure luck. How to incorporate these two key factors in our analysis, decision making, and ultimately investing process is probably the most critical question. Most diligent and smart people can learn valuation tools and see which company trades at a lower multiple. These days with the rise of big data, AI and super-computers - analysis and valuation are quickly becoming commoditised. Using judgement to decide which factors are important and which ones can be simply ignored, knowing when to take new information into account and when it can be ignored as pure noise - this is the skill which computers may struggle to develop for a while.

You buy a stock, it goes down, you buy more - it goes further down

One reason which made me think more about how to develop this Decision Making skill is my recent purchase of Alibaba stock. It ticked most of the boxes - a favourite stock facing regulatory uncertainty with many retail investors extrapolating current problems far into the future, while many institutional investors are simply cutting their exposure to China. The media is quick to draw a picture of an autocratic regime destroying private business as it tries to reassert its power.

Somehow, few wanted to look back at history to see that China embarked on such regulatory crusades every 2-3 years, trying to fix things quickly. There was little focus on underlying cashflows and profitability of Alibaba, the fact that it has accumulated over 1bn users on its platform, a scale that is hard to build overnight regardless of regulatory efforts or money spent. The market also seemed to have forgotten that Jack Ma has turned into a minority shareholder with an economic interest of just a few percent and has stepped down from basically all management roles in the company.

Of course, negative regulatory developments could still change the culture in the company turning it into a more cautious enterprise with a less entrepreneurial spirit, slower growth, lower profitability, especially if higher contributions to ’common prosperity’ become a norm in the future.

But would c. 50% decline in share price more than reflect those perceived risks? On my basic calculations, Alibaba was trading at about 5x EV/EBITDA for the core business, adjusting for the losses in new commerce formats as well as adjusting for the value of Cloud, a stake in Ant Financial and Investments.

I bought the stock in early September, only to see it decline by over 10% in just a few days. I added to my position and faced another 10% decline. Then I started questioning my assumptions, thinking about the real downside scenario, tried to understand how much I knew China, the risks of complete delisting and so on.

There was some new information released over the past few weeks as well.

So what initially looked like a high-quality company facing temporary difficulties’ started to look like as much more complex case. I neither added more or exited position since then.

And the point here is not really to discuss Alibaba’s investment case, but rather to focus on how we make decisions.

Books on How to Make Better Decisions

So far, I have read three very good books on this subject - a book by Philip Tetlock, Julia Galef and the first book by Annie Duke. I have almost finished reading Duke’s second book, which has much more practical content and tools.

I have recently added my reviews of Philip Tetlock’s ‘Superforecasting’ book and Julia Galef’s ‘Scout Mindset’ to the Library. I have a few other books on my list, including Nate Silver’s ’Signal and the Noise’, Bruce de Mesquita’s ‘The Predictioneer’s Game’, Adam Grant's 'Think Again' and others. To be fair, there is a lot of wisdom in best-sellers like Daniel Kahneman’s ‘Thinking Slow and Fast’ as well as James Montier’s ‘Behavioural Finance’, which I enjoyed a lot. But they mostly deal with our weaknesses that lead to our suboptimal decisions, but have fewer practical tools to improve our judgement.

I should also add that memos by Howard Marks are quite useful in setting the right framework for thinking and making investment decisions. I also enjoyed both of his books but have not written reviews on either of them yet. The first book - 'The Most Important Thing' - is based on some of his key Memos on Investing including Risk, Uncertainty and Luck. However, I do not recall many practical takeaways from the book that can be easily applied in one's investment process.

I hope learning such practical tools would take me less time than the first 20 years that I have spent trying to master valuation tools as well as accumulate knowledge on key industries.

Some short takeaways I have noted so far:

- Don't judge decisions by individual outcomes. The outcome of a particular decision depends on the quality of this decision and some element of luck. It is important to distinguish the role of luck in the final outcome from the quality of the decision itself.

- Problem of being too smart - you become good at explaining things, starting to look at the world in the more narrow way, leaving little room for luck. You are likely to suffer from confirmation bias (seeking evidence to confirm your original views) and hindsight bias (‘Of course, I knew it would happen’), which stops you from improving your process as true feedback is blocked. You cannot identify the flaws in your thinking process, you block new information to see reality better. Smart people tend to go deep into a particular problem and become ‘married’ to their ideas, with so much time invested and the concept looking so plausible. But often, just looking around for alternative explanations could be a better use of time as you get the true picture of reality faster and with less effort. This does require accepting limits to your knowledge and analytical skills and accepting that there are many much smarter people out there.

- Value investors can learn a lot from traders. I used to immediately disregard the views of people who did not view stocks as interests in real businesses and who focused on technical analysis, macro factors. But unlike fundamental investors, traders do not have big egos invested into single views and are much better at accepting mistakes. Risk management is a big area where traders are so much better. Unlike many fundamental investors, traders do not try to prove their opinion is right and others are wrong, they seek the truth whatever it is.

- Outside vs Inside views, base rates. Smart people often jump immediately into particular details of a specific situation, analysing it from the inside because they can easily find possible links and map out the problem. But a more useful starting point would be to look at base rates - what has historically happened in similar situations. Instead of thinking of Alibaba as a specific case, it could be useful to understand how often Chinese regulator ‘destroyed’ businesses, how often their actions were aimed to ‘destroying’ private businesses and slowing down the economy and so on. What happened to businesses which found themselves in similar situations. When did large profitable companies with net cash positions fail?

- Seek counterarguments. Many studies show that an average of an estimate made by a group (individually by members of a group) is closer to reality than the best forecast made by an individual from the same group. It is important to seek other views, facts and opinions that disagree with your thesis to improve your

- Superforecasters updated their estimates (forecasts) much more often than ‘experts’.

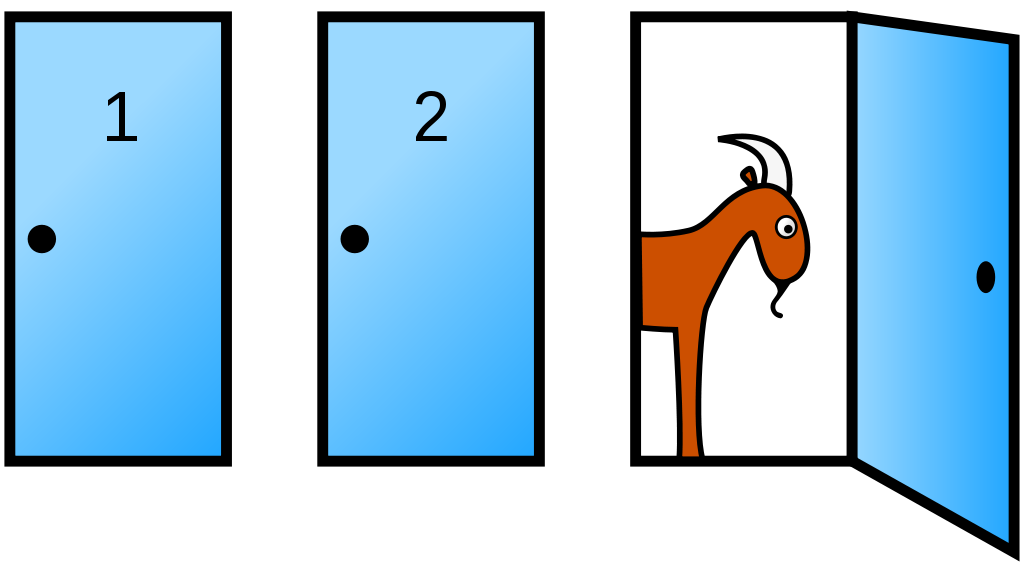

- Circle of competence, saying No to almost everything. This is so well-known to fans of Warren Buffett, but nevertheless, it is worth re-iterating, especially in light of various studies on decision making. Before trying to answer the question/making forecast, it is crucial to identify what is known and what is knowable, while what could be the result of various unpredictable factors (luck) and what could be there which we have not thought about. Decisions based on knowledge rather than guesses and concepts obviously win in the long term. Sticking to what you really know and slowly expanding your knowledge base is crucial.

There are many more useful tips and ideas in the book reviews I have posted in the Library.

Thank you for taking the time to read the post.

Did you find this article useful? If you want to read my next article right when it comes out, please subscribe to my email list.