For example, I often hear now this idea that best investors are entrepreneurs who are obsessed with their product, do not sell based on the share price or macro conditions and just keep focusing on the business. To back this idea, people refer to the Walton family, Jeff Bezos, Reed Hastings and so on.

I actually have some issues with this idea even if it initially sounds so convincing. First of all, I think there is quite possibly a hindsight bias at play here. When something or someone did very well, we try to explain it by looking backwards. Putting events into a logical consequence and combining them with personal traits of individuals, ultimate result (success) starts looking very obvious.

But imagine instead of looking back, you are looking forward. All of a sudden things look very different and much less obvious. Yes, the Walton family has accumulated c. $200bn fortune by keeping 99% of their wealth in one industry and one company. However, does it mean that the same family would be equally successfully over the next 20 years. Should investors follow the Waltons now after their track record or can they find companies that would generate higher returns on capital and whose shares will do better?

Secondly, if you simply try to find the next Walmart or Amazon today, you should remember that majority of new businesses fail. For every one Jeff Bezos there are hundreds and probably thousands of entrepreneurs who tried to do similar stuff online and may have had even better ideas or more drive but something did not work out. It is important not to forget the role of luck but also the base rate of failure when trying to find the next Amazon.

Nassim Taleb wrote well how we tend to under appreciate the role of chance in our lives preferring to look at the world as a logical place with events unfolding in a consequence where one action leads to another. I really recommend reading his first book - Fooled by Randomness.

After writing about my key investment principles, I kept thinking on what it takes to become a great investor. I have come to just three basic ideas:

- Stock is a share in a business.

- 90% of stocks are fairly priced.

- Good habits (financial hygiene) are sometimes more important than analytical skills and tools

Let’s look at each of them in more detail.

1. Stock is a share in a business.

This is a very important concept. If you think about it for a few minutes, you realise that to chose the right stock you need to chose the right business. The stock will eventually reflect performance of the underlying business. A business that keeps reinvesting capital at 30% will continue to grow its earnings at 30% a year. Over decades, the stock will generate returns close to this 30% level regardless of what PE multiple was at the moment of purchase.

The second idea coming from this concept is that you need to have patience to wait for the stock to reflect business fundamentals. Stock prices can change a lot in the short term as investors turn optimistic, overly excited or get cautious and then scared. But real businesses do not change over night, it takes years to develop a new product and more time is needed to successfully launch it and grow market share. Expecting to make overnight profits from investing is wrong.

But patience only pays off provided that you have done your homework: you know how the business is generating profits, you know what customers are really paying for, what alternative products are out there, you have learnt the background of key executives and their motivation.

Patience without proper analysis of the business is stubbornness and stupidity.

This concept also leads to another idea of ignoring macro forecasts. Of course macro conditions impact the bottom line and the share price. But successfully forecasting is almost impossible and redirects your attention from more important analysis of the business (as well as competitors, suppliers, customers etc). But perhaps the most important reason not to focus on macro is that economy is cyclical but grows over the long-term. Most short-term problems caused by recent macro issues will eventually be overcome.

Just imagine the risk of selling a great business (the one you have thoroughly analysed and understood) only because you are afraid that a possible slowdown in the economy could cause market correction.

The only area where macro conditions are worth paying somewhat attention are emerging markets and commodities. In EM it is important to differentiate between real and inflationary growth, and also to avoid vulnerable companies (e.g. who borrow at low cost in foreign currency but generate revenue from selling goods in local currency that can depreciate in the future).

Finally, there is quite useful one analytical tool that comes out of this idea which I try to use. Imagine you buy 100% of the business, rather than just a few shares. Or imagine the stock market closes for 10 years after you buy a stock in a company.

How would you know if your investment is worth more or less compared to your purchase price?

The way to assess the change in value (when you cannot check the share price or better even when share prices is available) is to measure how much earnings and dividends have changed over time. You also may want to take into consideration change in leverage, change in key investments including marketing and personnel and change in assets. This is necessary to make sure that profit growth was not achieved at the expense of long-term investments.

If a company boosts profits by acquiring new businesses using leverage without regards to prices or just buys out shares, its per-share earnings can grow for a while until the debt burden becomes unbearable.

A company can also cut half of its personnel and stop investing in its brand, cutting advertising and other promotional activities. This would have immediate impact on the bottom line but eventually consumers will switch to new products causing sales to drop with no cost cutting able to offset it.

So in normal circumstances the value of your investment would grow at a similar rate as profits of the company that you own would increase.

A simple way to assess your future annual return from a potential investment is to add dividend yield to a mid-term growth rate. It is of course important to use normal dividend rather than special (which, for example, includes proceeds from sale of assets).

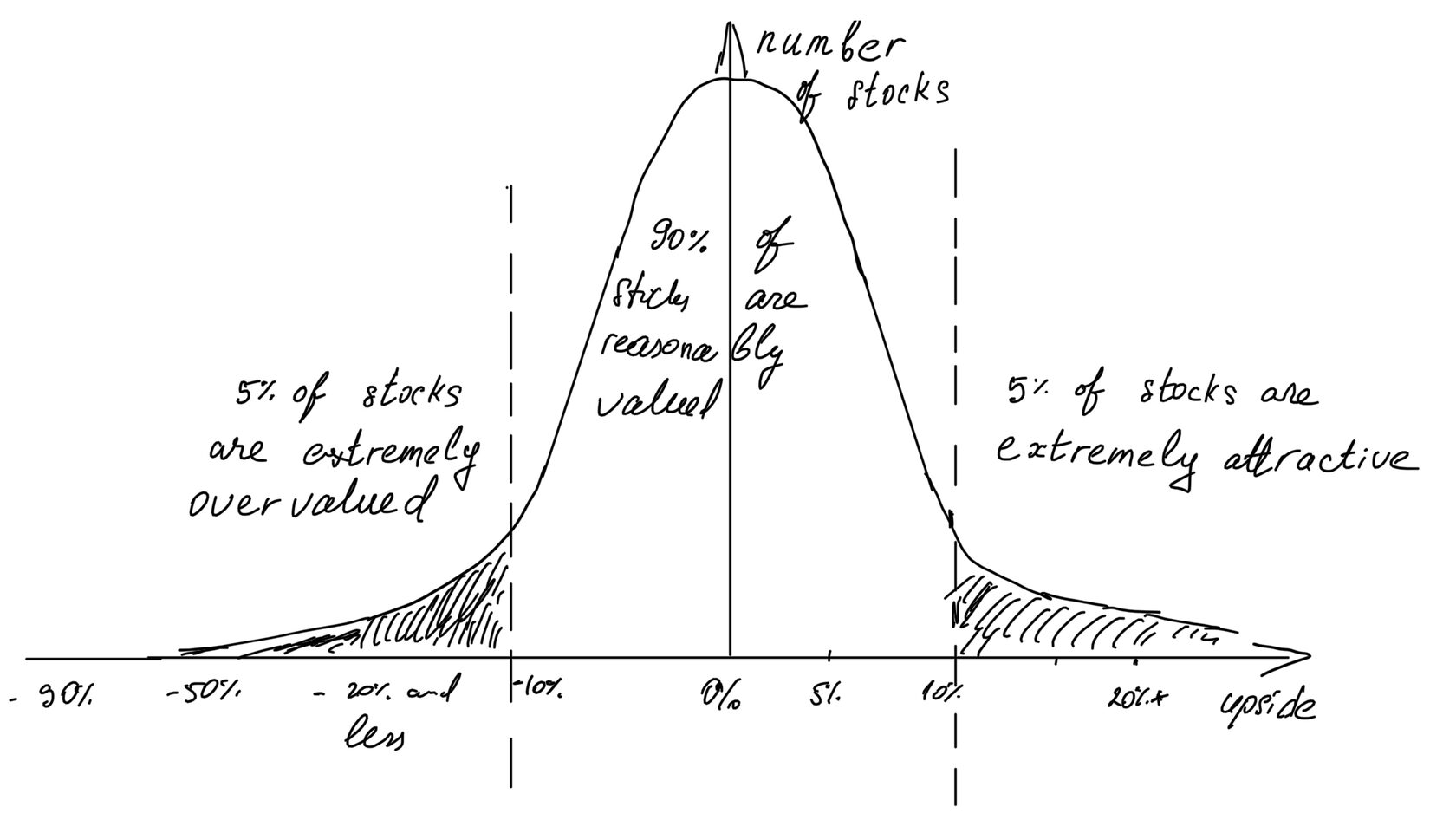

2. 90% of stocks are fairly priced.

For various reasons, we tend to either spend too much time analysing various stocks (this is my issue) or tend to take views on businesses quite lightly. I know people who can buy a stock relatively fast if it screens as a good business and has declined 30% on what appears to be a temporary issue.

Intelligent people are drawn to complex situations viewing them as a personal challenge that they should try to solve. This is partly my problem as I am quite competitive and like solving puzzles.

If you are running a fund and benchmark yourself against a broad market index, you almost always tend to look at all stocks in the index and your decisions become relative. Instead of identifying best opportunities (great companies sold for attractive prices) you tend to decide if you should be over-weight or under-weight a particular stock.

Since most stocks tend to be fairly valued, you waste your time on 90 out of 100 stocks and increase risks of making mistakes. It is obviously hard to justify high fees that a fund manager charges a client if he / she invests in just 5 names and does not have a large analyst team. What are you doing all the time? Do you have necessary intellectual capabilities? What is your view on Alibaba? Amazon? China vs US? USD vs EUR?

Not having answers to such questions may make such focused portfolio manager look unqualified and would impact his ability to attract money from investors.

Saying ‘I don’t know’ too many times would not help you move up in most jobs, not just in money management. A sell-side analyst going on a roadshow to meet with investors who keeps honestly saying ‘I don’t know’ would not be able to secure many meetings next time.

As a result, financial professionals tend to form dozens of opinions on things that they either do not have sufficient information on or that are simply not forecastable (not least because certain situations develop in non-linear fashion and can depend on opinions of others).

When I say that 90% of stocks are fairly valued, i don’t mean that their prices would remain flat for the rest of their lives. Quite the opposite - they may well be multi-baggers or head to zero.

But knowing in advance with high confidence which stocks would do what is almost impossible for at least 90% of them.

Stock market is a highly competitive space with many funds employing dozens of in-house analysts, they have access to industry analysts, management, other experts, often regulators and other parties. The amount of data that is available to most sophisticated investors is huge. This could include satellite data, speech patterns identified by special AI programmes, 100 years of industry data and so on.

When a normal person is going out to pick stocks for his personal portfolio, he should be fully aware of who he is going against.

The key conclusion from this is that you should be very careful with what you spend your time on. Very few opportunities could be truly compelling and you can get an edge in them (knowing a little more than an average investor, having a little more patience and being able to focus on the next 3-5 years rather than the next 3-5 quarters).

Having an edge without the extra effort is very hard. I will share my ways of getting an edge in the future, but one other message is that it takes a lot of effort both intellectual as well as physical to find an extra edge.

So it makes sense first to identify just few really compelling opportunities and then go deep on them, understanding every little piece about their business models, management background and motivation, competitive landscape, pipeline of future products and so on.

Since it takes so much effort to find an edge you naturally tend to invest less often and hold on to your positions for longer. This ties well with the first idea that stocks are interests in businesses and their prices eventually reflect underlying performance of these businesses.

This idea was also expressed by Warren Buffett when he talked about the ‘Fat pitch’ using baseball analogy. You don’t have to swing at every pitch. As Buffett often says:

“The trick in investing is just to sit there and watch pitch after pitch go by and wait for the one right in your sweet spot. And if people are yelling, ‘Swing, you bum!,’ ignore them.”

It pays off to be patient to wait for the best opportunity.

One other mental short cut could be to imagine that you have a punch card which you stamp every time you make an investment. As Buffett says to students,

“I could improve your ultimate financial welfare by giving you a ticket with only 20 slots in it, so that you had 20 punches — representing all the investments that you got to make in a lifetime. And once you’d punch through the card, you couldn’t make any more investments at all.”

3. Good habits (financial hygiene) are sometimes more important than analytical skills and tools

The final point is that stock selection, superb analytical tools, access to unique information - all these factors are responsible for just about half of total wealth creation and probably even less.

What is even more important is how much you invested in your stock ideas and for how long you have held them.

These two factors fall under the third principle which I call good investment habits or financial hygiene. Imagine you had some savings in 2009 and you made (a correct) decision that market sentiment was too negative and asset valuations too low. Your natural thought would be to look for possible investment opportunities.

Not having deep knowledge of particular businesses, you decided to put your savings into a broad market ETF.

Your friend, following the same logic about market conditions, decided to invest in individual stocks instead. With prior investment experience and willingness to do more research, your friend identified Amazon as his top investment.

You were comfortable to put all your savings (lets say 50% of your net worth at that time) into an ETF because you already owned a house, your regular salary more than covered basic expenses and you managed to save more money over time.

Your friend, worried about losses at Amazon and not willing to bet all his savings on just one stock, invested only 3% of his savings in Amazon.

In 2014, following a fivefold increase in his investment (lets assume the friend bought Amazon shares at $75 in May 2009) your friend decides to take profits and sells his position for $375.

He is proven right (at least for some time) as Amazon share declines below $300 during 2014.

You, on the other hand, not having ‘insightful’ stock ideas continue to keep your money in a market ETF and consider adding more as cash savings that you keep accumulating earn too low return.

By now (September 2021), you can see who would be wealthier.

If you invested half of your net worth in a S&P 500 index in May 2009, you would see your investment grow at least 5x by now and your total wealth increase 3x (assuming the value of your other assets remain constant).

A genius stock picker (your friend) would make 5x return from his investment in a shorter period of time, but his total wealth accumulation would be minuscule compared to the first investor.

Just to back this with some math. A 3% position in Amazon held for four years would generate 5x return. But total wealth of such investor would grow by just 12%.

Even if last 10 years were exceptionally good for overall stock market performance, investing large enough capital over a long period of time would increase your wealth more than exceptional stock picking with smaller amounts and over shorter time periods.

Why did this lucky Amazon investor sell his position in 2014, you may wonder. Well, there could have been plenty of ‘reasons’ - he could have started worrying about … inflation, interest rates, correction, recession, elections, geopolitics, budget deficit, trade wars (just choose any of your favourite worries).

The two major conclusions from this third idea is that Size and Time in the market generate as much wealth as smart stock picking and probably even more.

What are other ‘good’ investment habits?

- Saving regularly and adding to your portfolio, this allows to reduce risks of poor timing.

- Following more rules to avoid the impact of biases (not making decisions when you could be influenced by emotions).

- Avoiding personal leverage (having enough cash to cover your expenses if you lose a job during a crisis).

- Being more cautious when there is lots of euphoria around, paying more attention to prices / valuation during strong markets. Also being careful not to extrapolate earnings growth achieved during a period of strong economic growth (especially for consumer goods companies and retailers).

- Adding to your investments during periods of sharp market corrections, economic crisis.

- Tuning out the ‘noise’, not paying too much attention to external factors if the business that you own continues to be ‘great’, showing no signs of deteriorating competitive advantage.

- Having patience, not expecting regular positive returns evert 3-6-12 months. Not interrupting compounding when you don’t have to. Great companies can reinvest their profits at high returns growing their capital and profits in the future. The value of your investment would follow the growth of their profits and capital.