26 March 2023

I keep saying to those of my friends who are just starting their investment journey that their investment success depends on more than just picking the right stocks. In this post, I will share the mistakes I made in 2008 and what I have learnt since then. Those lessons are highly relevant in today’s environment.

I will also share some insights from the Make Better Decisions course by Annie Duke, which I am currently attending. At the end of this post, there are a couple of bonuses (one bonus available to subscribers only).

So, let’s dive in now.

Content:

I. How I navigated the 2008 crash

II. Lessons learnt and how to apply them today

III. The two insights from Annie Duke

IV. Bonus material

V. Conclusions

II. Lessons learnt and how to apply them today

III. The two insights from Annie Duke

IV. Bonus material

V. Conclusions

How I navigated the 2008 crash

I was a relatively young analyst working in a top hedge fund. The fund followed a market-neutral, event-driven strategy. We focused on finding fundamentally attractive stocks with some catalysts that could trigger re-rating (e.g. spin-offs, restructuring, change in management) and shorted other stocks or indices to maintain zero exposure to the market (Beta). The promise to our clients was Alpha!

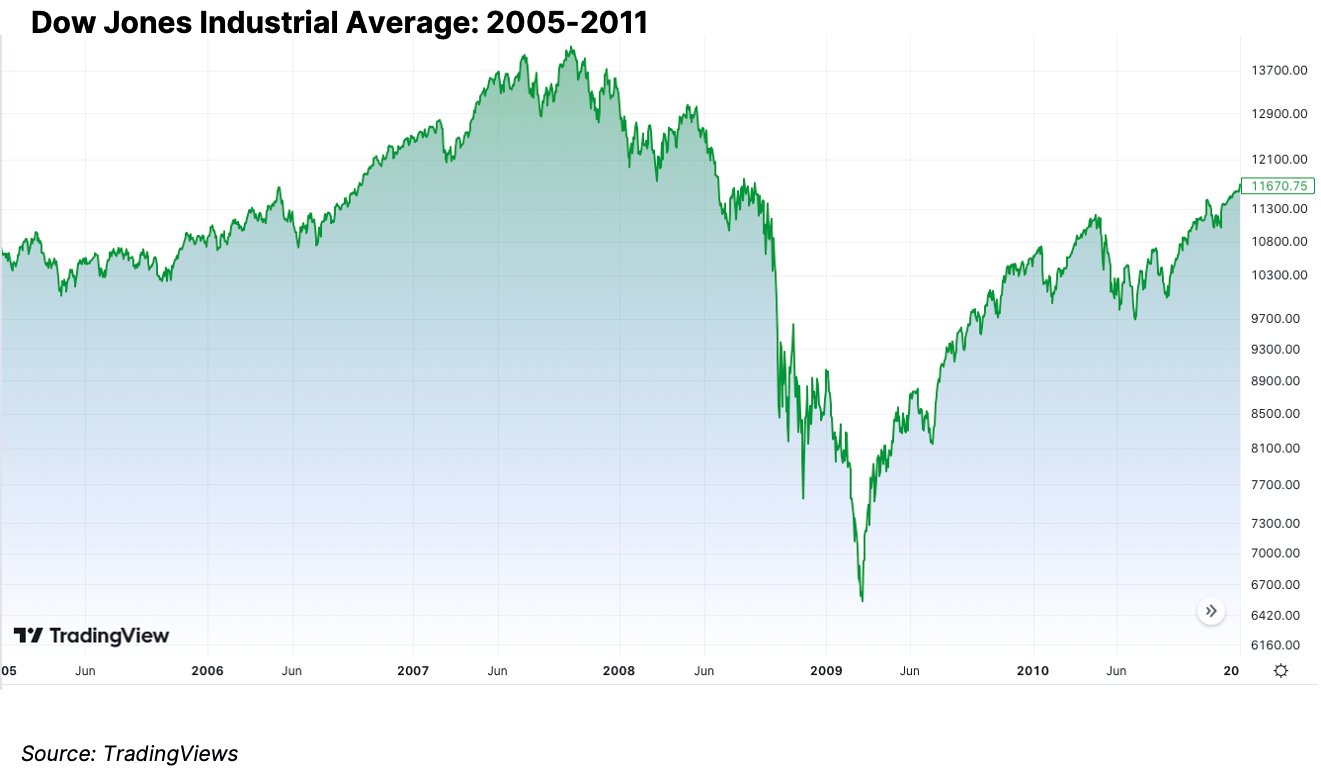

My interest in macro was first piqued in July 2007 when two large huge funds run by Bear Sterns reported losses of 90% and 100% and were liquidated. I remember reading a long article in the FT one summer Saturday about the problems in the credit markets. I had some unpleasant feelings but did not fully understand the issues. The names of Nassim Taleb and Nouriel Roubini still meant nothing to me then.

On August 16 2007, a few days after my birthday, the DJIA closed at 12,946, having declined for 12 out of the previous 20 trading days and was down 8.3%.

Like everyone, I was shocked to see the first bank run in my career happening in the UK when Northern Rock first reported its liquidity problems in September 2007 and was later nationalised.

Things started to get even more “exciting” in 2008. I bought my first book by Taleb, Black Swan (I read Fooled by Randomness later), and finally learnt who Nouriel Roubini was. If ’subprime’ was the word I learnt in 2007, ‘credit crunch’ was the term I got acquainted with in 2008.

You are probably curious about what I was doing with my portfolio. Well, firstly, it was tiny, so I did not care about it that much then. Secondly, I considered myself a ‘long-term’ and ‘patient’ investor. After all, I had already read The Intelligent Investor by then.

So I did not do much besides adding to my existing positions when I had a bit of savings. What was in my portfolio? There were about ten stocks, with Berkshire Hathaway being one of them. There were also a couple of ‘value’ stocks like BP and HSBC. Why not? They were both trading at a single PE, offering a 7% dividend yield. I was not too worried that these two metrics were the most widely followed indicators readily available for free on the Internet (even at that time). In other words, low valuation was more of a warning that these companies had some issues.

As you can see, both BP and HSBC turned out to be really poor investments which taught me that business fundamentals (returns on capital and reinvestment opportunities) were far superior factors compared to just a low valuation multiple.

More importantly for me personally was that I lost my job at the end of 2008 as our flagship fund suffered double-digit losses that year, despite promising our investors positive absolute returns (since we hedged the market risk and focused on Alpha, or at least that was what we thought we did).

The good thing was that I had almost half of my savings in cash, so I was not a forced seller during the crisis.

A couple of years later, I actually sold all of my stocks as I bought my first flat in 2010.

My interest in macro was first piqued in July 2007 when two large huge funds run by Bear Sterns reported losses of 90% and 100% and were liquidated. I remember reading a long article in the FT one summer Saturday about the problems in the credit markets. I had some unpleasant feelings but did not fully understand the issues. The names of Nassim Taleb and Nouriel Roubini still meant nothing to me then.

On August 16 2007, a few days after my birthday, the DJIA closed at 12,946, having declined for 12 out of the previous 20 trading days and was down 8.3%.

Like everyone, I was shocked to see the first bank run in my career happening in the UK when Northern Rock first reported its liquidity problems in September 2007 and was later nationalised.

Things started to get even more “exciting” in 2008. I bought my first book by Taleb, Black Swan (I read Fooled by Randomness later), and finally learnt who Nouriel Roubini was. If ’subprime’ was the word I learnt in 2007, ‘credit crunch’ was the term I got acquainted with in 2008.

You are probably curious about what I was doing with my portfolio. Well, firstly, it was tiny, so I did not care about it that much then. Secondly, I considered myself a ‘long-term’ and ‘patient’ investor. After all, I had already read The Intelligent Investor by then.

So I did not do much besides adding to my existing positions when I had a bit of savings. What was in my portfolio? There were about ten stocks, with Berkshire Hathaway being one of them. There were also a couple of ‘value’ stocks like BP and HSBC. Why not? They were both trading at a single PE, offering a 7% dividend yield. I was not too worried that these two metrics were the most widely followed indicators readily available for free on the Internet (even at that time). In other words, low valuation was more of a warning that these companies had some issues.

As you can see, both BP and HSBC turned out to be really poor investments which taught me that business fundamentals (returns on capital and reinvestment opportunities) were far superior factors compared to just a low valuation multiple.

More importantly for me personally was that I lost my job at the end of 2008 as our flagship fund suffered double-digit losses that year, despite promising our investors positive absolute returns (since we hedged the market risk and focused on Alpha, or at least that was what we thought we did).

The good thing was that I had almost half of my savings in cash, so I was not a forced seller during the crisis.

A couple of years later, I actually sold all of my stocks as I bought my first flat in 2010.

Lessons learnt and how to apply them today

I think this experience is quite valuable, especially since I learnt a few things the hard way. We tend to attribute great results to our skills and blame bad luck when we fail.

So here is what I have learnt since 2008:

So here is what I have learnt since 2008:

1. Volatility is the price we pay to achieve above-average investment results in the long-term

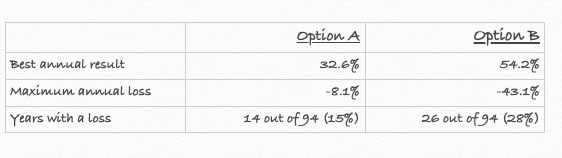

Suppose you are offered two investment options:

Which one would you choose?

At first glance, Option A is much better. Its worst annual return is -8.1%, and the product delivers annual losses only 15% of the time. Your investment would be growing 85% of the time.

Option B looks much riskier. In the worst year, you could be down 43.1%, and almost a third of the time, you can be losing money. The only upside is the maximum annual returns which can reach 54.2% compared to 32.6% for the safer Option A.

But are they worth it, given the risk profile of Option B?

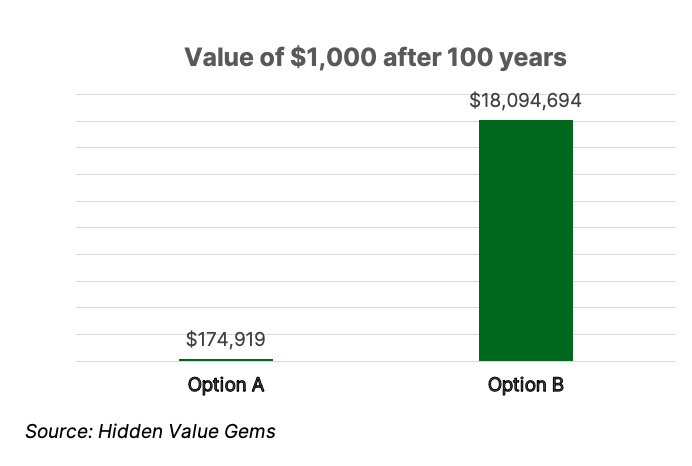

Consider the cumulative return of the two options over 100 years.

At first glance, Option A is much better. Its worst annual return is -8.1%, and the product delivers annual losses only 15% of the time. Your investment would be growing 85% of the time.

Option B looks much riskier. In the worst year, you could be down 43.1%, and almost a third of the time, you can be losing money. The only upside is the maximum annual returns which can reach 54.2% compared to 32.6% for the safer Option A.

But are they worth it, given the risk profile of Option B?

Consider the cumulative return of the two options over 100 years.

Low-risk bonds will increase the value of your portfolio from an original $1,000 to $174,919. In contrast, a stock portfolio with higher volatility will make you $18,094,694! This is more than 100x bigger gain!

This astonishing difference in returns comes from just a 5% difference and a very long holding period. Option A generates, on average, a 5.3% return a year, while Option B - 10.3%.

By now, you have probably guessed that Option A is a fixed-income portfolio, while Option B is the stock market. You can see more details and sources here.

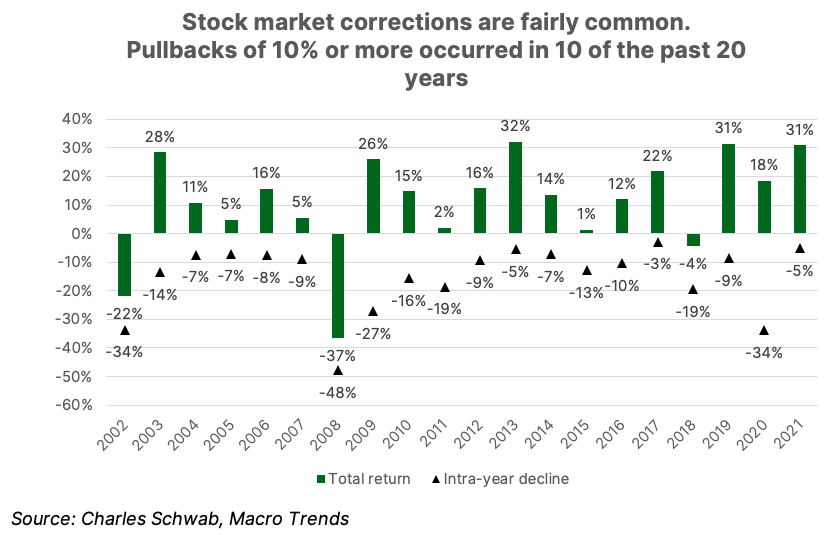

There are plenty of ways to discuss the volatility of stocks compared to bonds. Here is an example I borrowed from the Charles Schwab blog

This astonishing difference in returns comes from just a 5% difference and a very long holding period. Option A generates, on average, a 5.3% return a year, while Option B - 10.3%.

By now, you have probably guessed that Option A is a fixed-income portfolio, while Option B is the stock market. You can see more details and sources here.

There are plenty of ways to discuss the volatility of stocks compared to bonds. Here is an example I borrowed from the Charles Schwab blog

A decline of at least 10% occurred in 10 out of 20 years, or 50% of the time, with an average pullback of 15%. And in two additional years, the decline was just short of 10%. Despite these pullbacks, however, stocks rose in most years, with positive returns in all but 3 years and an average gain of approximately 7%.

The point is that when you are shown the cumulative returns of a stock portfolio over the long term vs bonds, you immediately opt for stocks. And you are almost offended when an advisor reminds you that “stocks are more volatile than bonds”. “Come on. I know that, it makes total sense, of course, I want a higher return in the end, so I choose stocks”, you utter.

But the advisor continues: “There were many periods when stocks generated negative returns over several years, you should be prepared to stay invested at least over five, better ten years.”

This will unlikely deter you, especially after seeing your neighbour move into a new house, as he luckily enjoyed a spectacular stock boom over the past ten years.

“I am ready for the short-term volatility. I am a long-term investor.”

These are almost exact words most people say at the beginning of their investment journey.

But are they?

It is easier to think we are rational when we read a book in an armchair, but when faced with losing 20% or 30% in less than a year, our minds start thinking differently.

WSJ columnist and author Jason Zweig put it well:

The point is that when you are shown the cumulative returns of a stock portfolio over the long term vs bonds, you immediately opt for stocks. And you are almost offended when an advisor reminds you that “stocks are more volatile than bonds”. “Come on. I know that, it makes total sense, of course, I want a higher return in the end, so I choose stocks”, you utter.

But the advisor continues: “There were many periods when stocks generated negative returns over several years, you should be prepared to stay invested at least over five, better ten years.”

This will unlikely deter you, especially after seeing your neighbour move into a new house, as he luckily enjoyed a spectacular stock boom over the past ten years.

“I am ready for the short-term volatility. I am a long-term investor.”

These are almost exact words most people say at the beginning of their investment journey.

But are they?

It is easier to think we are rational when we read a book in an armchair, but when faced with losing 20% or 30% in less than a year, our minds start thinking differently.

WSJ columnist and author Jason Zweig put it well:

If I ask you in a questionnaire whether you are afraid of snakes, you might say no. If I throw a live snake in your lap and then ask if you’re afraid of snakes, you’ll probably say yes—if you ever talk to me again.

2. A stock is a share of a business, not a piece of paper, that is quoted and traded every minute and second. The longer you hold a stock, the more important the return on capital is for your total investment results, while valuation becomes less relevant

My other big lesson from the 2008 crisis is that patience alone is not enough.

Every crisis has an immediate impact on valuation multiples as millions of investors reassess risks and future earnings. Actual earnings can also fall in the short term, but eventually, they return to their long-term trend. If the company fails to grow its profits, its share price will also lag.

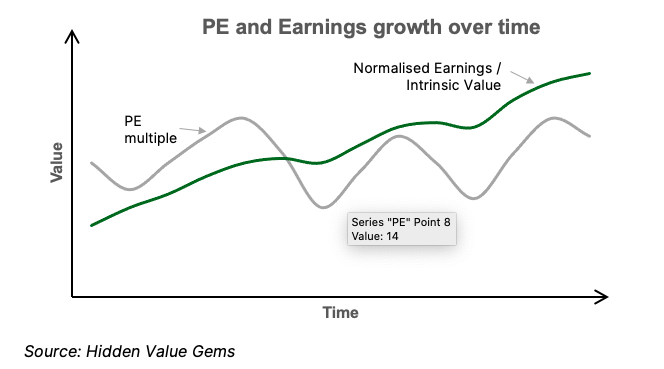

I like to refer to this chart to illustrate this concept.

Every crisis has an immediate impact on valuation multiples as millions of investors reassess risks and future earnings. Actual earnings can also fall in the short term, but eventually, they return to their long-term trend. If the company fails to grow its profits, its share price will also lag.

I like to refer to this chart to illustrate this concept.

One line (PE multiple) is much more volatile than the other (normalised earnings or intrinsic value). However, the first line also has boundaries. A typical stock fluctuates within a 10-20x PE range.

Normalised earnings cannot rise forever either, but their long-term limits are much higher.

Once the panic abates and a PE for a stock rebounds, it is the underlying earnings that drive returns going forward.

A few of my “value” stocks that I held prior to the 2008 crash went through a nose dive but did not collapse entirely. However, they also did not make me rich as they lacked sufficient earnings power.

So unless you are playing the game of market timing trying to anticipate what the market is pricing in now and how sentiment will change in the future, make sure your portfolio is made of companies that deliver long-term sustainable earnings growth.

Normalised earnings cannot rise forever either, but their long-term limits are much higher.

Once the panic abates and a PE for a stock rebounds, it is the underlying earnings that drive returns going forward.

A few of my “value” stocks that I held prior to the 2008 crash went through a nose dive but did not collapse entirely. However, they also did not make me rich as they lacked sufficient earnings power.

So unless you are playing the game of market timing trying to anticipate what the market is pricing in now and how sentiment will change in the future, make sure your portfolio is made of companies that deliver long-term sustainable earnings growth.

3. Every decade is unique, and there is always something to worry about

We often make mistakes thinking our circumstances are unique. If we go back in time, we can mistakenly get fixed on a particular time period. There is evidence that investors who experienced a big crash early in their career tend to be much more risk averse, expecting another big crash much more often than it actually happens.

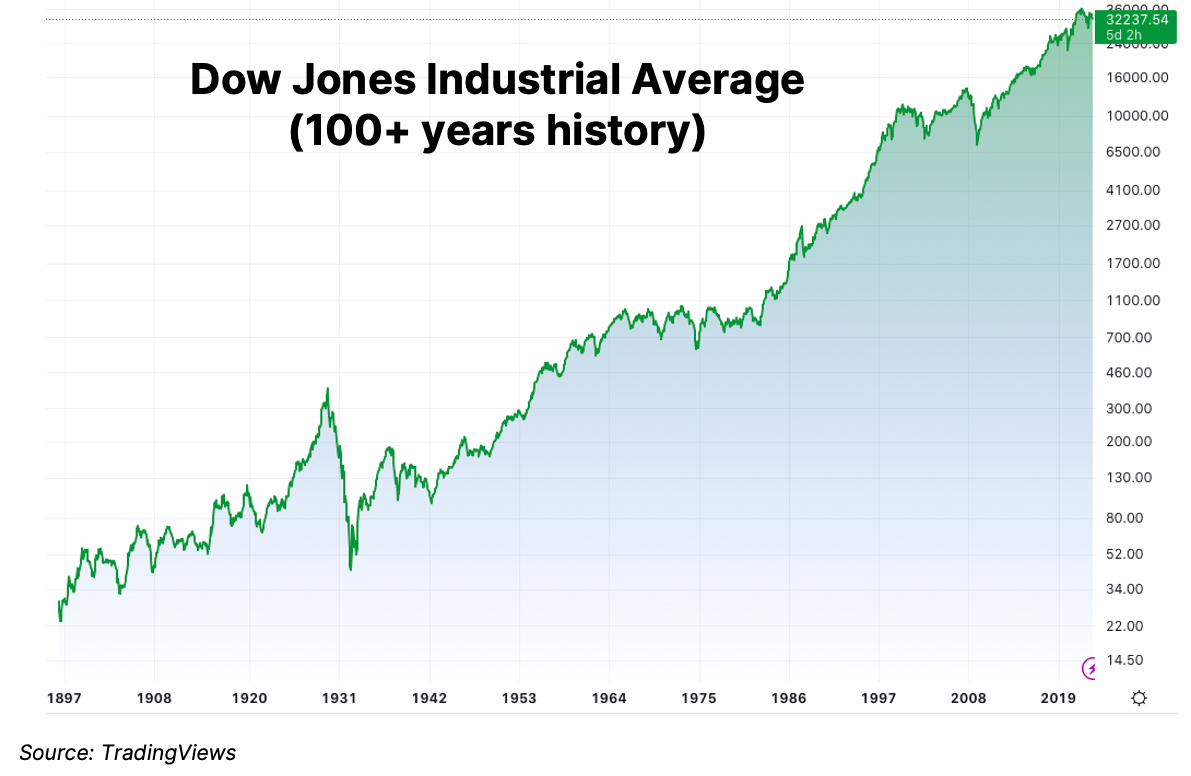

If we zoom out and look independently over 100+ years of financial history, it is logical to conclude that every decade is unique in its own way. This is my reminder to people who are today pointing out significant risks for the decade ahead (e.g. geopolitics, high starting valuation, massive debt, more polarised societies and the rise of populism).

I suggest carefully looking at every past decade on this chart. There are plenty of issues you can bring up for each past period.

If we zoom out and look independently over 100+ years of financial history, it is logical to conclude that every decade is unique in its own way. This is my reminder to people who are today pointing out significant risks for the decade ahead (e.g. geopolitics, high starting valuation, massive debt, more polarised societies and the rise of populism).

I suggest carefully looking at every past decade on this chart. There are plenty of issues you can bring up for each past period.

Wasn’t the 1910s unique? What about the 1920s (first a crash, then an epic bubble) and the 1930s? 1940s? The 1950s seem to be a bit more “normal” to me, but I am not a great historian and may miss something. I remember there was a Korean War that lasted three years (1950-1953). So hardly a peaceful decade.

And here is what History Channel says about the 1960s:

And here is what History Channel says about the 1960s:

The 1960s was one of the most tumultuous and divisive decades in world history. The era was marked by the civil rights movement, the Vietnam War and antiwar protests, countercultural movements, political assassinations and the emerging "generation gap."

I would also add that this was when the space era began. Hardly an ordinary event.

You can easily recall many unique circumstances about the 1970s, 1980s and other decades.

Peter Lynch famously said:

You can easily recall many unique circumstances about the 1970s, 1980s and other decades.

Peter Lynch famously said:

There's always something to worry about in investing. But it's a waste of time and energy because we won't predict it correctly. Investors become myopic when things aren't going our way.

Source: YouTube

You can learn more about Peter Lynch's view on macro and investment philosophy in my reviews of his two most famous books (One Up on Wall Street and Beating the Street).

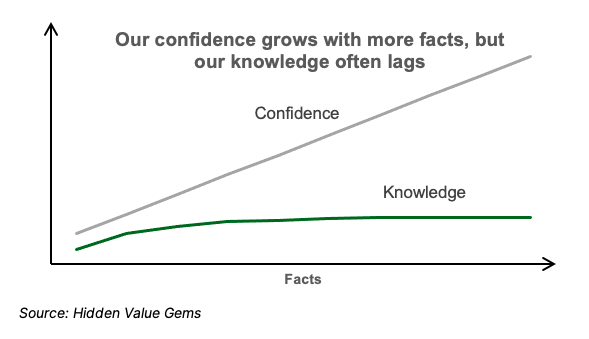

4. Do not seek certainty, embrace a wide range of outcomes

The danger of seeking clarity in a complex situation is that we subconsciously look for facts that just support our initial hypothesis (Confirmation bias). As we gather more data, our confidence rises even though our underlying knowledge may be constant. In the end, we fall victim to Overconfidence bias.

From my 2008 experience, I can observe that despite what people say now, the crisis did not look obvious or inevitable. Starting from 2007, it looked worrying, but the situation seemed to get under control each time authorities stepped in. For example, the government pushed for a quick acquisition of Bear Stearns by JP Morgan to avoid the bankruptcy of the former. The deal was wrapped on Sunday, 16 March 2008, before markets opened. S&P 500 was almost 4% higher by the end of March and 12% higher by mid-May.

There are two conclusions from this. Firstly, getting an edge in predicting a big crash takes a lot of work. Secondly, the risk of following the news day-by-day and minute-by-minute is that you will end up consuming tons of information and may conclude that you understand what is happening. Mistakenly, you can either go to 100% cash (sell all your holdings) or start timing the market by buying stocks that should benefit from a particular macro scenario.

Instead, all that time you spend reading articles and watching the news about global problems is better spent finding great businesses (if you really care about investing). A regular investment plan (making monthly contributions to a broad-market ETF) is also a good option if you don’t want to spend too much time thinking about markets.

Don’t forget that many people who came out as oracles during the crisis were permabears. They had been predicting a crisis for years before it happened (like Roubini). If you just listened to them, you would never invest in the stock market.

It can be bad this time too, or it may end up just fine - stop guessing. We will learn about the new genius after another crisis, but we will never know about thousands and millions of investors who got it wrong trying to make the best prediction.

There are two conclusions from this. Firstly, getting an edge in predicting a big crash takes a lot of work. Secondly, the risk of following the news day-by-day and minute-by-minute is that you will end up consuming tons of information and may conclude that you understand what is happening. Mistakenly, you can either go to 100% cash (sell all your holdings) or start timing the market by buying stocks that should benefit from a particular macro scenario.

Instead, all that time you spend reading articles and watching the news about global problems is better spent finding great businesses (if you really care about investing). A regular investment plan (making monthly contributions to a broad-market ETF) is also a good option if you don’t want to spend too much time thinking about markets.

Don’t forget that many people who came out as oracles during the crisis were permabears. They had been predicting a crisis for years before it happened (like Roubini). If you just listened to them, you would never invest in the stock market.

It can be bad this time too, or it may end up just fine - stop guessing. We will learn about the new genius after another crisis, but we will never know about thousands and millions of investors who got it wrong trying to make the best prediction.

5. Do you have a bulletproof portfolio? Secrets to successfully going through big crashes

Once you find yourself amidst a storm, you realise the importance of preparation. It is crucial to think of downside risks while still on land. Buying insurance against a hurricane is always better during normal weather.

This is what the CEO of Charles Schwab, Walt Bettinger, said this week:

This is what the CEO of Charles Schwab, Walt Bettinger, said this week:

Many times, when you’re in a crisis, there’s very little you can do. It all comes down to what actions you had taken in preparation for that.

I do not think that it is too late to high grade your portfolio even now. Why?

Because the key in investing is to avoid complete losses (ruin) and do not interrupt the compounding process. Consider this example: what would you choose - 1 million today or a penny that doubles every day for 30 days. Most people immediately go for 1 million dollars. The penny that doubles daily would be worth $1.28 after the first week. After the second week, it would be worth $163.84. A long way to catch up, but just wait for the magic of compounding to play out. On Day 30, the total value grows to…..$10,737,418.24! An astonishing result (at least, to me).

Even more interesting is that most of the value in absolute terms was created in the last few days. On the 26th day, the value is still below $1 million ($671,089), but in just 4 last days, it exceeds $10 million! Losing a few days in this process can have a dramatic impact on the total value. Imagine that, worse, on the days that the value does not compound, it actually goes down.

This is why in real-world investing, it is critical to own businesses that can continue to compound their capital for as long as possible without interruptions. High-growth start-ups that depend on external capital or leveraged commodity producers are the opposite of that. You can make more money if you time your purchases well, but if something goes wrong, the results will be dreadful.

These are the characteristics of companies that are part of my bulletproof portfolio:

Because the key in investing is to avoid complete losses (ruin) and do not interrupt the compounding process. Consider this example: what would you choose - 1 million today or a penny that doubles every day for 30 days. Most people immediately go for 1 million dollars. The penny that doubles daily would be worth $1.28 after the first week. After the second week, it would be worth $163.84. A long way to catch up, but just wait for the magic of compounding to play out. On Day 30, the total value grows to…..$10,737,418.24! An astonishing result (at least, to me).

Even more interesting is that most of the value in absolute terms was created in the last few days. On the 26th day, the value is still below $1 million ($671,089), but in just 4 last days, it exceeds $10 million! Losing a few days in this process can have a dramatic impact on the total value. Imagine that, worse, on the days that the value does not compound, it actually goes down.

This is why in real-world investing, it is critical to own businesses that can continue to compound their capital for as long as possible without interruptions. High-growth start-ups that depend on external capital or leveraged commodity producers are the opposite of that. You can make more money if you time your purchases well, but if something goes wrong, the results will be dreadful.

These are the characteristics of companies that are part of my bulletproof portfolio:

- Low financial leverage.

- They do not depend on external funding to grow.

- Low operating leverage (relatively low fixed costs).

- They generate good profit margins and FCF.

- They produce important products for consumers and have unique qualities (low risk of a product becoming obsolete, like Kodak).

- They generate good returns on capital (above 10%).

- Their value is less sensitive to macro conditions (e.g. commodity producers or banks).

- They are run by managers with “skin-in-the-game” (high insider ownership).

The above characteristics apply to the so-called Quality businesses. The flip side is that owning them in boom times may be tough. Their stocks may do nothing compared to hot sectors like AI or commodities. The thought that you are in the wrong assets will often daunt you in such moments. It may be even harder to stick to them if you run the client’s money.

I also believe that having some cash in your portfolio (at least 5%, perhaps 10% or even 15%) will help you go through the storm stronger and achieve better results over the long term.

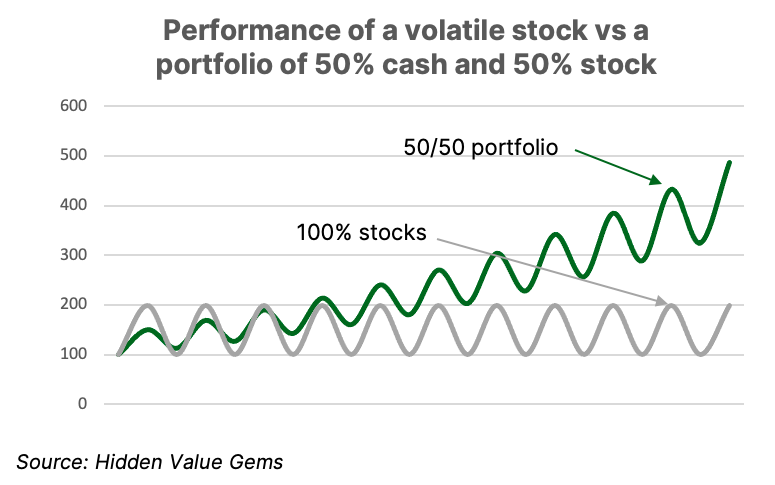

Consider this example which I borrowed from William Poundstone's book Fortune’s Formula.

I also believe that having some cash in your portfolio (at least 5%, perhaps 10% or even 15%) will help you go through the storm stronger and achieve better results over the long term.

Consider this example which I borrowed from William Poundstone's book Fortune’s Formula.

There are two portfolios on this chart. The first one is fully invested in a highly volatile stock that goes down 50% or doubles yearly. The second portfolio is only 50% invested in the same stock, while the other half is invested in cash (assumed to generate zero returns). Each time the stock goes up, an investor sells some of it to rebalance the cash position to 50% of the total value of the portfolio. When the stock declines, an investor buys it to rebalance the weights of stock and cash to 50/50.

In 22 years, the value of the second portfolio will be 387% higher (up almost fivefold), much better than the performance of the first portfolio (which fluctuates between flat and 100% all of the time). Moreover, the second portfolio is also less volatile, with the worst drawdown of only 25% compared to 50% for the first portfolio.

In 22 years, the value of the second portfolio will be 387% higher (up almost fivefold), much better than the performance of the first portfolio (which fluctuates between flat and 100% all of the time). Moreover, the second portfolio is also less volatile, with the worst drawdown of only 25% compared to 50% for the first portfolio.

6. What else do you need to withstand the crash?

It is critical to avoid running your life on leverage. That means not just trading on margins but having enough savings to live for a year without the need to find a new job or sell your stocks.

Our personal leverage is often much higher than we think. We may have zero debt and believe we are safe. But if you rent a flat with only a month of savings, you cannot afford to lose your job. Even if you have more savings and all of them are in an equity portfolio, there is a high risk that in a downturn, you may lose your job and be forced to sell some of your holdings at lower prices.

Expenses related to health issues are also hard to plan for. Still, you may need that extra cash at an unexpected moment, so consider having extra savings to cover those expenses too.

The benefit of having cash is that not only it gives you peace of mind, but also you can take advantage of falling prices during a downturn and buy great companies at much better prices.

Our personal leverage is often much higher than we think. We may have zero debt and believe we are safe. But if you rent a flat with only a month of savings, you cannot afford to lose your job. Even if you have more savings and all of them are in an equity portfolio, there is a high risk that in a downturn, you may lose your job and be forced to sell some of your holdings at lower prices.

Expenses related to health issues are also hard to plan for. Still, you may need that extra cash at an unexpected moment, so consider having extra savings to cover those expenses too.

The benefit of having cash is that not only it gives you peace of mind, but also you can take advantage of falling prices during a downturn and buy great companies at much better prices.

7. Will all of this help?

Even if you only buy high-quality businesses at reasonable prices, you will still face a drop in the market value of your portfolio, perhaps even quite a significant one. The surest thing to avoid this is to keep your savings in cash, but then you will not be able to benefit from long-term economic growth.

Fluctuations in the prices of your stocks are inevitable. This is the price you pay to earn a 10% annual return over the long term.

This is not to say that we are in a benign market environment.

It appears to me that the risks are skewed to the downside. I do not think the stocks are pricing in all the risks. While the credit quality of banks’ loans is higher than in 2008 (wait until the economy starts deteriorating), there are other challenges which did not exist back then.

There is a record amount of sovereign debt, inflation is high, and geopolitical risks are also higher, while China is gradually slowing down and cannot provide the same boost to global growth as it did in 2009.

As for the three recent bank failures in the US (Silvergate, Signature Bank and Silicon Valley Bank), unfortunately, other mid-tier banks may also be under pressure. While most other banks are more diversified (both in terms of their deposit base and exposure of loans to different sectors of the economy), they still face the mark-to-market losses of their bond portfolio. And many smaller banks also face deposits outflow as savers seek better products (e.g. money-market funds).

However, the overall banking system cannot lose all its deposits because about 57% were insured as of the end of 2022. Companies and individuals still need to keep their money somewhere for day-to-day activities. So it is likely that larger banks will see an inflow of deposits.

Having said that, the net impact will be a lower credit growth as banks will focus on holding more liquid assets and having more capital rather than on winning the new business. This will be a drag on the economy and corporate profits — a similar effect to rising interest rates.

This is only one of the outcomes, but other potential developments may take place in parallel, such as the Fed starting to cut interest rates or energy prices falling further. Both would be positive for consumer spending.

I will stop discussing macro scenarios as it can be a never-ending process.

The main point is that it is better to be on the defensive side, not to own levered companies with low margins, and to have a higher cash position. Still, it does not make sense to sell all the stock holdings in anticipation of a big crash because it may or may not happen, and frankly, no one knows if and when it will happen.

Fluctuations in the prices of your stocks are inevitable. This is the price you pay to earn a 10% annual return over the long term.

This is not to say that we are in a benign market environment.

It appears to me that the risks are skewed to the downside. I do not think the stocks are pricing in all the risks. While the credit quality of banks’ loans is higher than in 2008 (wait until the economy starts deteriorating), there are other challenges which did not exist back then.

There is a record amount of sovereign debt, inflation is high, and geopolitical risks are also higher, while China is gradually slowing down and cannot provide the same boost to global growth as it did in 2009.

As for the three recent bank failures in the US (Silvergate, Signature Bank and Silicon Valley Bank), unfortunately, other mid-tier banks may also be under pressure. While most other banks are more diversified (both in terms of their deposit base and exposure of loans to different sectors of the economy), they still face the mark-to-market losses of their bond portfolio. And many smaller banks also face deposits outflow as savers seek better products (e.g. money-market funds).

However, the overall banking system cannot lose all its deposits because about 57% were insured as of the end of 2022. Companies and individuals still need to keep their money somewhere for day-to-day activities. So it is likely that larger banks will see an inflow of deposits.

Having said that, the net impact will be a lower credit growth as banks will focus on holding more liquid assets and having more capital rather than on winning the new business. This will be a drag on the economy and corporate profits — a similar effect to rising interest rates.

This is only one of the outcomes, but other potential developments may take place in parallel, such as the Fed starting to cut interest rates or energy prices falling further. Both would be positive for consumer spending.

I will stop discussing macro scenarios as it can be a never-ending process.

The main point is that it is better to be on the defensive side, not to own levered companies with low margins, and to have a higher cash position. Still, it does not make sense to sell all the stock holdings in anticipation of a big crash because it may or may not happen, and frankly, no one knows if and when it will happen.

The two insights from Annie Duke

I want to share two insights from the training Make Better Decisions by Annie Duke, which I recently completed.

The first one has to do with the Regret bias. It may look similar to the Loss Aversion bias, but it is not the same. The Regret bias deals with situations when we are afraid to make a decision because we will regret it. To avoid having this regret, we avoid making any decision at all.

Consider the situation of falling share prices that we find ourselves in today. There are more headlines on growing economic risks in the media, with social networks amplifying the negative messages.

If you buy a stock today, its market price will likely be lower next month or even in six months. Many of us have been in such a situation before. To avoid it, we do not buy anything and wait until the situation becomes more apparent, and headlines improve.

But is it the best strategy if your goal is to maximise returns in the next ten years?

If you do not have high personal leverage, you do not depend on the income from your portfolio to maintain current consumption; then you are better off buying during a crisis.

Warren Buffett is famous for explicitly warning Berkshire shareholders that he will make more mistakes in the future. Once you admit the two statements, making better decisions will be more straightforward:

The second statement also refers to the Regret bias when we fear that the stock we buy will not be as successful as some of the best Tech businesses, which have generated over 30% annual returns for many years.

By definition, such businesses are exceptional (outliers) and buying a portfolio made only of such companies is impossible. Of course, if a million people buy a portfolio of 10 random stocks, a few of them will end up with such outliers. But this is the result of luck, not skill.

The second insight I learnt from Annie Duke is

The first one has to do with the Regret bias. It may look similar to the Loss Aversion bias, but it is not the same. The Regret bias deals with situations when we are afraid to make a decision because we will regret it. To avoid having this regret, we avoid making any decision at all.

Consider the situation of falling share prices that we find ourselves in today. There are more headlines on growing economic risks in the media, with social networks amplifying the negative messages.

If you buy a stock today, its market price will likely be lower next month or even in six months. Many of us have been in such a situation before. To avoid it, we do not buy anything and wait until the situation becomes more apparent, and headlines improve.

But is it the best strategy if your goal is to maximise returns in the next ten years?

If you do not have high personal leverage, you do not depend on the income from your portfolio to maintain current consumption; then you are better off buying during a crisis.

Warren Buffett is famous for explicitly warning Berkshire shareholders that he will make more mistakes in the future. Once you admit the two statements, making better decisions will be more straightforward:

- I guarantee that at least one stock I buy will be a failure, and its share price will be lower in the future.

- I guarantee that I will miss a few stocks that will turn out to be the next Google or Amazon.

The second statement also refers to the Regret bias when we fear that the stock we buy will not be as successful as some of the best Tech businesses, which have generated over 30% annual returns for many years.

By definition, such businesses are exceptional (outliers) and buying a portfolio made only of such companies is impossible. Of course, if a million people buy a portfolio of 10 random stocks, a few of them will end up with such outliers. But this is the result of luck, not skill.

The second insight I learnt from Annie Duke is

When it is too hard to choose between the two options, it means it is easy.

Imagine you were in 2009. You realise the crisis is not permanent and are considering adding to your equity portfolio. You are hesitating about what stock to buy, Google or Amazon. You can spend months researching both of them, reading annual reports, talking to fellow investors, studying competitors etc.

The best thing which could happen to you is that you buy one of them a year later. However, if you just did a flip coin to speed up your decision-making process, your total net worth would be higher if you bought any of them in 2009 because both companies were phenomenal businesses available at fantastic prices.

As Annie Duke says, “when it is too hard, that means it’s easy”. Choosing between the two options is hard because they are both excellent.

The Regret bias could also lead you to suboptimal position size. A person who picked Amazon in 2010 and allocated 3% of his funds would have done worse than someone who bought a market ETF a year earlier (in 2009) and allocated 30% of his funds to that position.

The best thing which could happen to you is that you buy one of them a year later. However, if you just did a flip coin to speed up your decision-making process, your total net worth would be higher if you bought any of them in 2009 because both companies were phenomenal businesses available at fantastic prices.

As Annie Duke says, “when it is too hard, that means it’s easy”. Choosing between the two options is hard because they are both excellent.

The Regret bias could also lead you to suboptimal position size. A person who picked Amazon in 2010 and allocated 3% of his funds would have done worse than someone who bought a market ETF a year earlier (in 2009) and allocated 30% of his funds to that position.

Bonus material

If you are still with me, I would like to reward you for your patience with a couple of things.

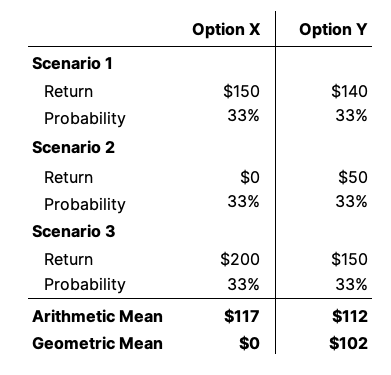

My second reward is a bonus material which I would like to share. This is a fairly basic concept of two averages - arithmetic and geometric. Quite often, when making an investment decision, we try to work out its Expected Value using the arithmetic mean. We consider several scenarios, estimate the potential return for each scenario and probabilities for those scenarios. Then we multiply the return by probability and sum up the results.

This method has serious disadvantages and can lead to severe losses. In certain situations, the geometric mean is a better way to calculate the expected value of an investment decision.

Imagine you need to choose between two investment opportunities (X and Y). Both opportunities require an initial investment of $100. Both of them have three possible outcomes, with an equal probability (1/3).

This method has serious disadvantages and can lead to severe losses. In certain situations, the geometric mean is a better way to calculate the expected value of an investment decision.

Imagine you need to choose between two investment opportunities (X and Y). Both opportunities require an initial investment of $100. Both of them have three possible outcomes, with an equal probability (1/3).

Most people would go for X since its expected value calculated in a usual way is higher by $5. However, in Scenario 2, you lose your entire investment ($100) if you go with X. Y will also generate losses in Scenario 2, but you will keep $50.

If you invest all your money in Option X and do it continuously, you will end up broke one day. At the same time, you will never lose all your money even if you bet all of it all of the time on Option Y.

You can read more about this in my old post Why most people lose money in the stock market? The big math secret.

If you invest all your money in Option X and do it continuously, you will end up broke one day. At the same time, you will never lose all your money even if you bet all of it all of the time on Option Y.

You can read more about this in my old post Why most people lose money in the stock market? The big math secret.

Conclusions

1. The risks seem to be skewed to the downside, and stocks may well end up being lower in the short- and medium-term.

2. However, as long as you do not rely on your investment portfolio to cover your daily expenses, it is better to consider buying great companies at lower prices, as their values will likely rise in the long term.

3. Volatility is the price we pay to achieve better results over the long term.

4. You can spend all your time studying macro risks and still get it wrong. It is almost impossible to forecast the next crash. You better use that time on studying great businesses.

5. The key qualities of companies that can withstand the crash are low leverage, high operating margins, and high returns on capital. Their products are in high demand and do not face the risk of becoming obsolete.

6. To avoid Regret bias, remind yourself that at least one stock you buy will end up a flop. I guarantee that you will also miss a few stocks that will end up becoming the next Google. Do not waste time chasing between two great businesses when they are down 30-50%. Just buy one of them or both.

2. However, as long as you do not rely on your investment portfolio to cover your daily expenses, it is better to consider buying great companies at lower prices, as their values will likely rise in the long term.

3. Volatility is the price we pay to achieve better results over the long term.

4. You can spend all your time studying macro risks and still get it wrong. It is almost impossible to forecast the next crash. You better use that time on studying great businesses.

5. The key qualities of companies that can withstand the crash are low leverage, high operating margins, and high returns on capital. Their products are in high demand and do not face the risk of becoming obsolete.

6. To avoid Regret bias, remind yourself that at least one stock you buy will end up a flop. I guarantee that you will also miss a few stocks that will end up becoming the next Google. Do not waste time chasing between two great businesses when they are down 30-50%. Just buy one of them or both.

Did you find this article helpful? If you want to read my next article right when it comes out, please subscribe to my email list.