9 July 2023

Until a few years ago, whenever I met a person who said he was a macro or a day trader, I immediately looked for a reason to end the conversation. I thought I had nothing in common with traders. After all, I was educated on the classic books of Graham and Lynch, who viewed a stock as a share in a business rather than a piece of paper whose prices goes up and down. Both were highly critical of market activity that was not classified as investing.

But not any more. These days I am quite happy to continue the conversation. Not because I am interested in their views on the future direction of the market. They have certain qualities that we, value investors, often lack and should try to learn.

Let me explain.

Investors’ biggest sin

After the first edition of The Intelligent Investor was published in 1949, speculation became a synonym for investors’ sin.

The “dean” of Value Investing, Ben Graham, emphasised the difference between an Investor and a Speculator and warned of the latter's high risks and mediocre results. In Chapter 8 of his classic book, he wrote:

The “dean” of Value Investing, Ben Graham, emphasised the difference between an Investor and a Speculator and warned of the latter's high risks and mediocre results. In Chapter 8 of his classic book, he wrote:

“The most realistic distinction between the investor and the speculator is found in their attitude toward stock-market movements. The speculator’s primary interest lies in anticipating and profiting from market fluctuations. The investor’s primary interest lies in acquiring and holding suitable securities at suitable prices.”

- Benjamin Graham

He also added:

“It is easy for us to tell you not to speculate; the hard thing will be for you to follow this advice. Let us repeat what we said at the outset: If you want to speculate do so with your eyes open, knowing that you will probably lose money in the end…”

The five hidden powers of traders

Classic financial textbooks often explain the value of traders in generating liquidity for the financial system. Thanks to this, fundamental investors can buy or sell securities at prices they consider fair and without disturbing them.

But there is much more.

Here are at least five underappreciated skills of traders:

But there is much more.

Here are at least five underappreciated skills of traders:

I. Discipline to follow the rules

Real traders have an explicit system which they follow with rigorous discipline. Most ordinary people believe they have a plan until they face big losses, in which case they look for a new system or leave the market. But it is the consistency of applying your method and following the routine that distinguishes top traders from everyone else.

In any activity where luck is present, the process trumps the outcome. The best poker players are fine losing small amounts of money for several hours in a row as long as they make the right decisions: those with the highest expected return (outcome times probability).

American doctor Atul Gawande in The Checklist Manifesto showed how breaking down complex high-pressure tasks into small steps can radically improve the results of human actions, from flying planes to carrying out complex surgeries.

One study reported that the implementation of the Surgical Safety Checklist in the US led to a 36% reduction in the rate of inpatient complications and a 47% decrease in surgical mortality across eight hospitals in eight different countries. The use of checklists has helped reduce human errors in aviation accidents by 65%, according to the US Federal Aviation Administration.

In his recent book Noise, the world’s most famous behavioural scientist, Daniel Kahneman, reviewed the quality of predictions of human judgement relative to a simple formula. He concluded that simple mechanical rules were generally superior. He also reviewed various other studies, all of which came to the same conclusion: professionals are distressingly weak in what they often see as their unique strength - the ability to integrate information.

One of the core reasons why models beat humans is that we tend to be “noisy”, to borrow Kahneman’s term. In other words, we are inconsistent. When presented with the same facts, we may arrive at different conclusions depending on when we look at them. Models, on the other hand, are consistent.

In any activity where luck is present, the process trumps the outcome. The best poker players are fine losing small amounts of money for several hours in a row as long as they make the right decisions: those with the highest expected return (outcome times probability).

American doctor Atul Gawande in The Checklist Manifesto showed how breaking down complex high-pressure tasks into small steps can radically improve the results of human actions, from flying planes to carrying out complex surgeries.

One study reported that the implementation of the Surgical Safety Checklist in the US led to a 36% reduction in the rate of inpatient complications and a 47% decrease in surgical mortality across eight hospitals in eight different countries. The use of checklists has helped reduce human errors in aviation accidents by 65%, according to the US Federal Aviation Administration.

In his recent book Noise, the world’s most famous behavioural scientist, Daniel Kahneman, reviewed the quality of predictions of human judgement relative to a simple formula. He concluded that simple mechanical rules were generally superior. He also reviewed various other studies, all of which came to the same conclusion: professionals are distressingly weak in what they often see as their unique strength - the ability to integrate information.

One of the core reasons why models beat humans is that we tend to be “noisy”, to borrow Kahneman’s term. In other words, we are inconsistent. When presented with the same facts, we may arrive at different conclusions depending on when we look at them. Models, on the other hand, are consistent.

II. Focus on downside risks

Traders religiously focus on the downside. They know that to win big, they have to stay in the game for as long as possible, and that means avoiding risks of ruin/complete loss of capital. Novice investors, including young value investors, put too much emphasis on how cheap a particular stock is and how significant its potential upside is. They often simplify the concept of Margin of Safety introduced by Ben Graham, thinking that low price takes care of potential downside risks.

Many great investors, who are hardly traders, put downside risks first. Remember Buffett’s famous two rules of investing?

Many great investors, who are hardly traders, put downside risks first. Remember Buffett’s famous two rules of investing?

“Rule number one: Don’t lose money. Rule number two: Never forget the first rule.”

- Warren Buffett

When asked how he decides on position size, Joel Greenblatt, one of the world’s best value investors, said the following:

When asked how he decides on position size, Joel Greenblatt, one of the world’s best value investors, said the following:

“If I think I can make 10x my money, that doesn’t make it my favourite investment. If I can invest a lot of money and I don’t see how I’m gonna lose anything and maybe make five or ten per cent, that might be a much better risk-reward for me. So typically, my largest positions have been the ones where I don’t think I can lose money.”

Great traders also know their limits and have low regard for their knowledge. As a result, they focus much more on what they don’t know rather than seeking evidence that supports their current view.

A value investor with one of the best track records, Seth Klarman, constantly emphasises the importance of protecting against the downside risks:

A value investor with one of the best track records, Seth Klarman, constantly emphasises the importance of protecting against the downside risks:

“The best investors do not target return; they focus first on risk, and only then decide whether the projected return justifies taking each particular risk.”

- Seth Klarman, co-founder of the Baupost Group

III. They have a low Ego and can cut losses fast

Traditional value investors often misinterpret the virtue of patience. It helps to maintain long-term focus only if you own a unique business that can compound its capital at high returns for many years ahead or, at least, if the company remains on solid footing. But history suggests that this is more an exception than the norm.

Business failures are much more common than enduring growth.

The act of buying on valuation grounds is also an act of arrogance. Essentially you claim that you know the fair price of a company better than the market, the millions of various market participants, even though some of them may have better access to critical information or better analytical resources.

The chances that you are right cannot be high for an ordinary person. Especially today when multiples for most listed companies are available to anyone for free.

So having humility and admitting to making a mistake is crucial for any value investor who wants to succeed. This is the hardest for us to do for several reasons. Firstly, we face sunk costs bias. Having invested days and weeks into researching a specific company, we feel that all this time will be wasted if we just sell the shares and move on. We are also afraid to be viewed as inconsistent and incompetent if we publicly announce a stock to be a great value and then change our minds a few weeks later.

For many unfortunate investors being right is more important than making money. Moreover, highly intelligent people often struggle to perceive the world as a random place. Instead, they look for cause-effect relationships. Their ideal version of the world is not only fair but also reasonable and organised.

Such people are gullible enough to believe in various stories with little evidence. Potential investment opportunities presented in the form of a great story are often the most appealing options to such people. Even when they use their analytical skills, they usually collect facts that fit a narrative rather than prove it or leave explanations to pure luck.

But this is not how the best forecasters operate. During 1987-2003, Philip Tetlock, a University of Pennsylvania psychologist, carried out an experiment, asking 284 participants various questions about the future. He identified a small group of people who consistently beat all others, including the world’s famous experts in their respective fields. I found it fascinating, but according to Tetlock, people made worse predictions in their areas of expertise. More knowledge made them worse forecasters!

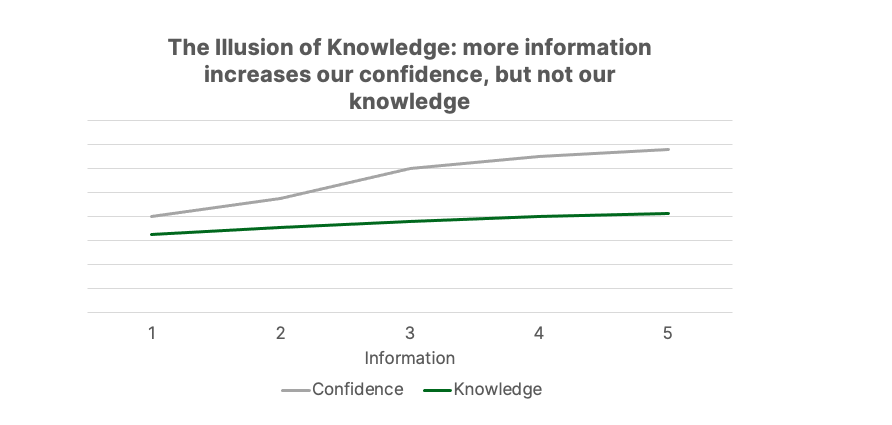

Other studies have identified Overconfidence as one of the biases prevalent among experts. Here is the chart that shows that the more information we possess on a topic, the more confident our judgement gets, while accuracy doesn’t improve!

Business failures are much more common than enduring growth.

The act of buying on valuation grounds is also an act of arrogance. Essentially you claim that you know the fair price of a company better than the market, the millions of various market participants, even though some of them may have better access to critical information or better analytical resources.

The chances that you are right cannot be high for an ordinary person. Especially today when multiples for most listed companies are available to anyone for free.

So having humility and admitting to making a mistake is crucial for any value investor who wants to succeed. This is the hardest for us to do for several reasons. Firstly, we face sunk costs bias. Having invested days and weeks into researching a specific company, we feel that all this time will be wasted if we just sell the shares and move on. We are also afraid to be viewed as inconsistent and incompetent if we publicly announce a stock to be a great value and then change our minds a few weeks later.

For many unfortunate investors being right is more important than making money. Moreover, highly intelligent people often struggle to perceive the world as a random place. Instead, they look for cause-effect relationships. Their ideal version of the world is not only fair but also reasonable and organised.

Such people are gullible enough to believe in various stories with little evidence. Potential investment opportunities presented in the form of a great story are often the most appealing options to such people. Even when they use their analytical skills, they usually collect facts that fit a narrative rather than prove it or leave explanations to pure luck.

But this is not how the best forecasters operate. During 1987-2003, Philip Tetlock, a University of Pennsylvania psychologist, carried out an experiment, asking 284 participants various questions about the future. He identified a small group of people who consistently beat all others, including the world’s famous experts in their respective fields. I found it fascinating, but according to Tetlock, people made worse predictions in their areas of expertise. More knowledge made them worse forecasters!

Other studies have identified Overconfidence as one of the biases prevalent among experts. Here is the chart that shows that the more information we possess on a topic, the more confident our judgement gets, while accuracy doesn’t improve!

One of the key differences between novice value investors and smart traders is how they treat information. More facts often make a value investor more convinced in her position or often shrugged off (“a quarterly report is irrelevant, I am thinking five years ahead”). Top traders, instead, can easily change their minds if the new information contradicts their original thesis.

Tetlock discovered the same trait among the group he called “Superforecasters”. They were open-minded. They changed their opinions more often and regularly updated their views in small increments.

This is much easier to do if you admit the limits of your knowledge.

In one of my recent posts, I shared the astonishing fact that Warren Buffett sold 60% of the stocks within the first 12 months after buying them. In other words, his typical holding period is less than a year - entirely opposite of a stereotype of a man whose favourite holding period is “forever”. But this is one of Buffett’s underappreciated strengths. He is ruthless at admitting mistakes and fixing them. He continues to hold stocks only when he has a strong conviction.

Tetlock discovered the same trait among the group he called “Superforecasters”. They were open-minded. They changed their opinions more often and regularly updated their views in small increments.

This is much easier to do if you admit the limits of your knowledge.

In one of my recent posts, I shared the astonishing fact that Warren Buffett sold 60% of the stocks within the first 12 months after buying them. In other words, his typical holding period is less than a year - entirely opposite of a stereotype of a man whose favourite holding period is “forever”. But this is one of Buffett’s underappreciated strengths. He is ruthless at admitting mistakes and fixing them. He continues to hold stocks only when he has a strong conviction.

IV. Respect for the wisdom of crowds and base rates

Being aware of the limits of their knowledge, successful traders respect crowd opinions and rarely argue with them. Focused on the downside risks, smart operators are more interested in knowing what they don’t know than what they know.

Following a trend is, in fact, acknowledging that the market knows something and is probably right.

Since Graham wrote Chapter 8 of his seminal book The Intelligent Investor, new generations of value investors have started to hold the broader market in low esteem. Graham created this image of Mr Market, who “often…lets his enthusiasm or his fears run away with him, and the value he proposes to you seem a little short of silly”.

This analogy plays bad tricks on young investors who assume the market price is wrong by default, and they can (easily) take advantage of it. Novice value investors make every effort to be contrarian all the time.

Various studies, however, have found that crowds are more often right than wrong especially compared to the opinions of individual experts.

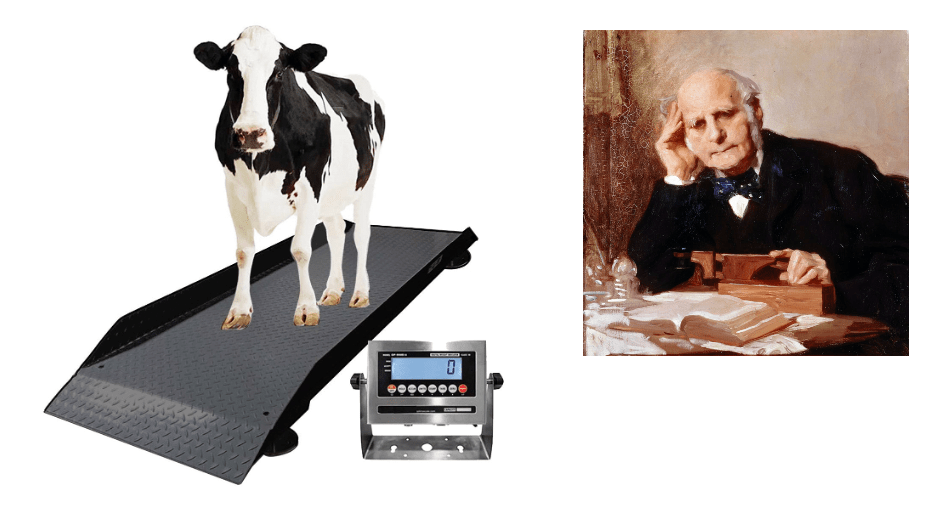

The so-called Wisdom of crowds phenomenon became widely known after Francis Galton, a cousin of Darwin and a famous polymath, observed a village contest. About 800 villagers at a country fair tried to estimate the weight of a prize ox. None of the villagers guessed the actual weight of the ox, which was 1,198 pounds, but the mean of their guesses was 1,200, just 2 pounds off, and the median (1,207) was also very close. The crowd made a better prediction than any individual from that group.

Following a trend is, in fact, acknowledging that the market knows something and is probably right.

Since Graham wrote Chapter 8 of his seminal book The Intelligent Investor, new generations of value investors have started to hold the broader market in low esteem. Graham created this image of Mr Market, who “often…lets his enthusiasm or his fears run away with him, and the value he proposes to you seem a little short of silly”.

This analogy plays bad tricks on young investors who assume the market price is wrong by default, and they can (easily) take advantage of it. Novice value investors make every effort to be contrarian all the time.

Various studies, however, have found that crowds are more often right than wrong especially compared to the opinions of individual experts.

The so-called Wisdom of crowds phenomenon became widely known after Francis Galton, a cousin of Darwin and a famous polymath, observed a village contest. About 800 villagers at a country fair tried to estimate the weight of a prize ox. None of the villagers guessed the actual weight of the ox, which was 1,198 pounds, but the mean of their guesses was 1,200, just 2 pounds off, and the median (1,207) was also very close. The crowd made a better prediction than any individual from that group.

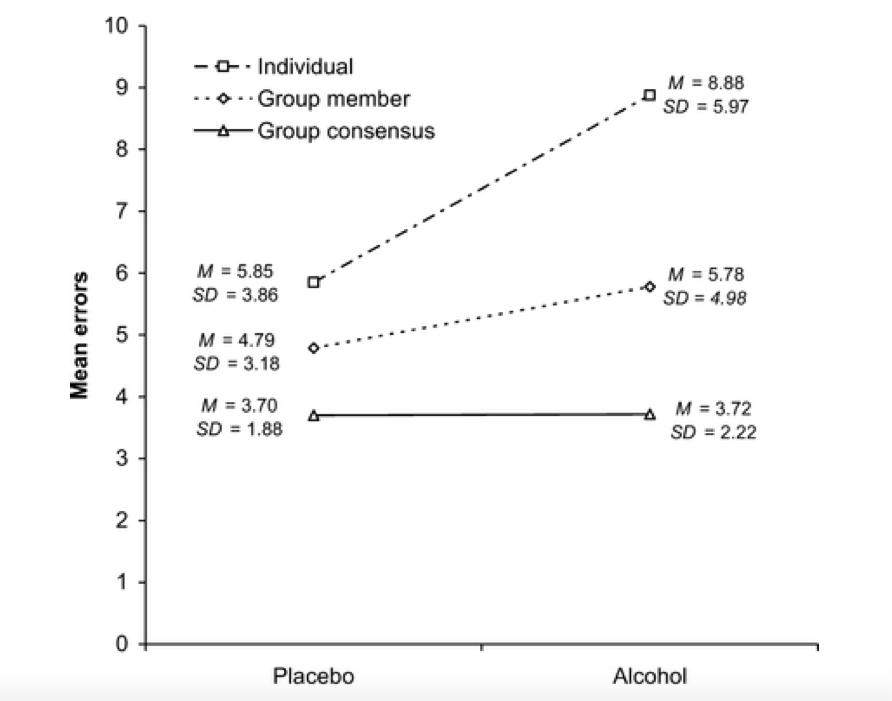

I was amazed to learn that this wisdom of crowds works even if the public is totally drunk. At least this has been the result of the study carried out by British professors in 2008. In their experiment, 286 students had to listen and count the number of times the word “the” had occurred in a passage about Russian history. Half of the students were drinking alcohol during the experiment, while the other half were drinking “placebo”.

The estimates were first made individually, and then the group had to arrive at a consensus decision. The results are shown on the chart below:

The estimates were first made individually, and then the group had to arrive at a consensus decision. The results are shown on the chart below:

The first conclusion is obvious: alcohol impairs your judgement, so may I remind you not to make important decisions after drinking. Drunk students made much bigger mistakes (mean error of 8.88), and there was much more “noise” in their judgements (standard deviation of 5.97).

However, the difference between drunk and sober students was much less significant when results were calculated for a small group in which students made estimates individually: mean error of 5.78 and 4.79, respectively. Random mistakes cancelled each other out.

But the most astonishing result came from consensus decisions: when groups of students (sober or drunk) had to agree on a consensus estimate. Drunk groups made the same error as groups of normal students! Albeit, the standard deviation was a little higher for drunks.

Graham is right that market prices can drift way too far from the fair value of individual businesses, but this happens once every three-to-five years, certainly not every month or week. Most of the time, stock prices adequately reflect fair values given the available information. The new generation of value investors admits it. On a recent podcast, Todd Combs described his preferred method of looking at stocks (42nd minute):

However, the difference between drunk and sober students was much less significant when results were calculated for a small group in which students made estimates individually: mean error of 5.78 and 4.79, respectively. Random mistakes cancelled each other out.

But the most astonishing result came from consensus decisions: when groups of students (sober or drunk) had to agree on a consensus estimate. Drunk groups made the same error as groups of normal students! Albeit, the standard deviation was a little higher for drunks.

Graham is right that market prices can drift way too far from the fair value of individual businesses, but this happens once every three-to-five years, certainly not every month or week. Most of the time, stock prices adequately reflect fair values given the available information. The new generation of value investors admits it. On a recent podcast, Todd Combs described his preferred method of looking at stocks (42nd minute):

“The game I have always played with myself is [this]: look at the name, do you work, build up what you would buy that entire business for. 80-90% of the time, your estimate is within 20% of the actual market cap.”

After taking those steps, Combs leaves only stocks for which his estimated value is multiple times different from the market cap. He explains that such an approach allows him to avoid narratives and anchoring and have a clearer view of the business. Not surprisingly, the year before that podcast, Ted Weschler described his method that looked almost identical.

When presented with a specific problem that requires making a judgement about the future, most investors start looking into specific details of a particular case. But recent studies on decision-making have found that looking at the base rate first is more helpful. The base rate shows how often a similar event has happened previously.

From my experience, traders are particularly good at looking at base rates first and then looking at why a specific case should differ. Many value investors in their early years often start with individual characteristics of the case and do not look for historical precedents.

When presented with a specific problem that requires making a judgement about the future, most investors start looking into specific details of a particular case. But recent studies on decision-making have found that looking at the base rate first is more helpful. The base rate shows how often a similar event has happened previously.

From my experience, traders are particularly good at looking at base rates first and then looking at why a specific case should differ. Many value investors in their early years often start with individual characteristics of the case and do not look for historical precedents.

V. Better sizing depending on conviction, not just upside

Throughout my career, I have seen many smart investors and traders. But what differentiated the really successful ones from everyone else was the ability to assess their conviction and size their bets accordingly. For most people, more information implies more confidence and more understanding.

But for astute traders/investors, it is not so straightforward. A lot of information is backwards-looking or reflects consensus views. Often, what we view as facts are opinions of individuals who may be biased or misinformed. Data presented as a story that reduces uncertainty looks much more convincing than random facts.

The best operators do not simply decide in Yes or No terms but can adjust their views in small probability terms. Most people are not good at seeing the difference between a probability of an event of 25% and 33%.

The examples of two completely opposite investors come to mind: Stanley Druckenmiller’s Pound call and Charlie Munger’s portfolio.

One of the best investors of our lives, Charlie Munger, is famous for allocating 99% of his wealth across just three investments: Berkshire Hathaway, Costco and Li Lu’s Himalaya Capital. He believes such a portfolio carries lower risks because it represents excellent businesses run by the best managers, and he understands those businesses well.

Compare that to a portfolio of a young aspiring value investor who often buys 50 or more stocks simply because they are “cheap” and offer significant upside. What about the level of risks and their ability to understand the businesses really well?

In his 2015 talk at the Lost Tree Club, Druckenmiller shared his frustration with how his mentor, George Soros, beat his performance even though Soros spent just 10% of his time on investments and simply copied ideas from Druckenmiller. The reason was the level of conviction and position sizing. Soros bet more heavily on the best ideas that Druckenmiller developed.

It is also very instructive how Soros came up with a short position in the British pound in 1992. Druckenmiller realised that the Bank of England would have to let the pound weaken against the Deutsche mark. Druckenmiller, managing both Duquesne and Soros Fund at that time, initially had a $1.5bn short position in the British pound. The fund was $7bn overall. When more news supporting his thesis came out later that year, he was about to short the remainder $5bn to make it 100% position for the fund. He briefly told Soros about his plans and reasons. Here is the rest of the story from the first hands:

But for astute traders/investors, it is not so straightforward. A lot of information is backwards-looking or reflects consensus views. Often, what we view as facts are opinions of individuals who may be biased or misinformed. Data presented as a story that reduces uncertainty looks much more convincing than random facts.

The best operators do not simply decide in Yes or No terms but can adjust their views in small probability terms. Most people are not good at seeing the difference between a probability of an event of 25% and 33%.

The examples of two completely opposite investors come to mind: Stanley Druckenmiller’s Pound call and Charlie Munger’s portfolio.

One of the best investors of our lives, Charlie Munger, is famous for allocating 99% of his wealth across just three investments: Berkshire Hathaway, Costco and Li Lu’s Himalaya Capital. He believes such a portfolio carries lower risks because it represents excellent businesses run by the best managers, and he understands those businesses well.

Compare that to a portfolio of a young aspiring value investor who often buys 50 or more stocks simply because they are “cheap” and offer significant upside. What about the level of risks and their ability to understand the businesses really well?

In his 2015 talk at the Lost Tree Club, Druckenmiller shared his frustration with how his mentor, George Soros, beat his performance even though Soros spent just 10% of his time on investments and simply copied ideas from Druckenmiller. The reason was the level of conviction and position sizing. Soros bet more heavily on the best ideas that Druckenmiller developed.

It is also very instructive how Soros came up with a short position in the British pound in 1992. Druckenmiller realised that the Bank of England would have to let the pound weaken against the Deutsche mark. Druckenmiller, managing both Duquesne and Soros Fund at that time, initially had a $1.5bn short position in the British pound. The fund was $7bn overall. When more news supporting his thesis came out later that year, he was about to short the remainder $5bn to make it 100% position for the fund. He briefly told Soros about his plans and reasons. Here is the rest of the story from the first hands:

“As I am talking, he [Soros] starts wincing like what is wrong with this kid. And I think he is about to blow away my thesis and he says, “That is the most ridiculous use of money management that I ever heard. What you described is an incredible one-way bet. We should have 200 per cent of our net worth in this trade, not 100 per cent. Do you know how often something like this comes around? Like one in 20 years. What is wrong with you?”.

Takeaways

Great investors like Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger have much more in common with great traders like George Soros and Stanley Druckenmiller than we usually think.

I hope the above ideas convinced you that there is more to successful investing than just looking for undervalued companies. Having rules and following discipline is important. Having a checklist and patience to let opportunities pass until you find the best one is critical. Sometimes the price is expensive; other times, it is the level of competitive advantage that is not strong enough.

Thinking about what could go wrong also helps you make better decisions rather than seeking facts that prove you are right.

By default, we lack all the necessary information to have 100% conviction in most cases. Besides, the world is an uncertain place, and we need to accept it rather than try to make it logical and simple. Reviewing the new information after you make an investment is crucial. Even more important is the ability to change your mind even partially (for example, by reducing the size of your position).

Just like all of us, I made more mistakes at the beginning of my investing journey. I overweighted the price factor and considered the broader market to be the dumb and emotional crowd that was more wrong than right.

Now, I pay more attention to downside risks thinking more about what could go wrong. Although, I think that I still do not spend enough time on this.

Some examples of this improved strategy include reducing my Altria position once I saw that the brand lacks the pricing power I expected it to have. I recently sold EPAM because I realised my conviction was not strong enough, as I had not fully understood its business model. The stock was priced as a 20-30% growth company (when, in fact, it is going to deliver a sales decline this year).

It is this awareness of things that I may not know that keeps my VW* and Kistos positions as relatively small. In the case of Kistos, I also expect the commodity market to be volatile and Kistos’ stock to have extra volatility due to its low liquidity.

At the same time, my biggest positions are in Berkshire Hathaway, Exor and Loews, all of which have much smaller downside risks than the general market (from my point of view).

I hope the above ideas convinced you that there is more to successful investing than just looking for undervalued companies. Having rules and following discipline is important. Having a checklist and patience to let opportunities pass until you find the best one is critical. Sometimes the price is expensive; other times, it is the level of competitive advantage that is not strong enough.

Thinking about what could go wrong also helps you make better decisions rather than seeking facts that prove you are right.

By default, we lack all the necessary information to have 100% conviction in most cases. Besides, the world is an uncertain place, and we need to accept it rather than try to make it logical and simple. Reviewing the new information after you make an investment is crucial. Even more important is the ability to change your mind even partially (for example, by reducing the size of your position).

Just like all of us, I made more mistakes at the beginning of my investing journey. I overweighted the price factor and considered the broader market to be the dumb and emotional crowd that was more wrong than right.

Now, I pay more attention to downside risks thinking more about what could go wrong. Although, I think that I still do not spend enough time on this.

Some examples of this improved strategy include reducing my Altria position once I saw that the brand lacks the pricing power I expected it to have. I recently sold EPAM because I realised my conviction was not strong enough, as I had not fully understood its business model. The stock was priced as a 20-30% growth company (when, in fact, it is going to deliver a sales decline this year).

It is this awareness of things that I may not know that keeps my VW* and Kistos positions as relatively small. In the case of Kistos, I also expect the commodity market to be volatile and Kistos’ stock to have extra volatility due to its low liquidity.

At the same time, my biggest positions are in Berkshire Hathaway, Exor and Loews, all of which have much smaller downside risks than the general market (from my point of view).

Note: VW is no longer part of HVG portfolio. I sold it later in 2023.

If you found this article useful, consider subscribing to my Newsletter to receive an email when a new post is published.