11 June 2023

Content:

I. Google’s secret laboratory

II. Bullett Train saga

III. What stops us from cutting losses early

IV. Quitting can be the biggest secret of Warren Buffett

V. Four steps to cut losses early

VI. How I started implementing this technique in practice

II. Bullett Train saga

III. What stops us from cutting losses early

IV. Quitting can be the biggest secret of Warren Buffett

V. Four steps to cut losses early

VI. How I started implementing this technique in practice

I. Google’s secret laboratory

Google is one of the world’s most innovative companies and the most sought-after employers for the most brilliant engineers globally. Billions of people use its products like Search and Maps daily. Its competitive advantage in Search and, eventually, digital advertising has been the subject of many case studies.

But what is less known is the secret laboratory behind many of the firm’s inventions called Google X. It was born in 2010, when Google founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin decided to form a new division to work on moonshots: radical new technologies that would solve humanity’s great problems. The company’s goal is a “10x impact on the world’s most intractable problems, not just 10% improvement.”

Waymo, the world’s most advanced driverless car company (by mileage driven), originated within X. Google Brain, the deep-learning division that now empowers everything from Google Search to Translate, began at X. So did camera software GCam, used in Google Pixel phones; indoor mapping in Google Maps; and Wear OS, Android’s operating system for wearable devices.

But what is less known is the secret laboratory behind many of the firm’s inventions called Google X. It was born in 2010, when Google founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin decided to form a new division to work on moonshots: radical new technologies that would solve humanity’s great problems. The company’s goal is a “10x impact on the world’s most intractable problems, not just 10% improvement.”

Waymo, the world’s most advanced driverless car company (by mileage driven), originated within X. Google Brain, the deep-learning division that now empowers everything from Google Search to Translate, began at X. So did camera software GCam, used in Google Pixel phones; indoor mapping in Google Maps; and Wear OS, Android’s operating system for wearable devices.

Meet the “Captain of Moonshots”

Astro Teller is the CEO of X. His official title is “Captain of Moonshots”. He likes to point out that X is not so much a company as a radical way of thinking, a method of pursuing technological breakthroughs by taking crazy ideas seriously. X’s job is not to invent new Google products but to produce the inventions that might form the next Google.

With the world’s top talent and dozens of billions of cashflows, you would think that finding solutions to problems is less of an issue. It is identifying problems to focus on that is the most challenging. Every million and month spent on a bad idea is wasted resources that could have been used to find other solutions that could change the lives of millions of people.

So how does Astro Teller decide which projects they should fund?

With the world’s top talent and dozens of billions of cashflows, you would think that finding solutions to problems is less of an issue. It is identifying problems to focus on that is the most challenging. Every million and month spent on a bad idea is wasted resources that could have been used to find other solutions that could change the lives of millions of people.

So how does Astro Teller decide which projects they should fund?

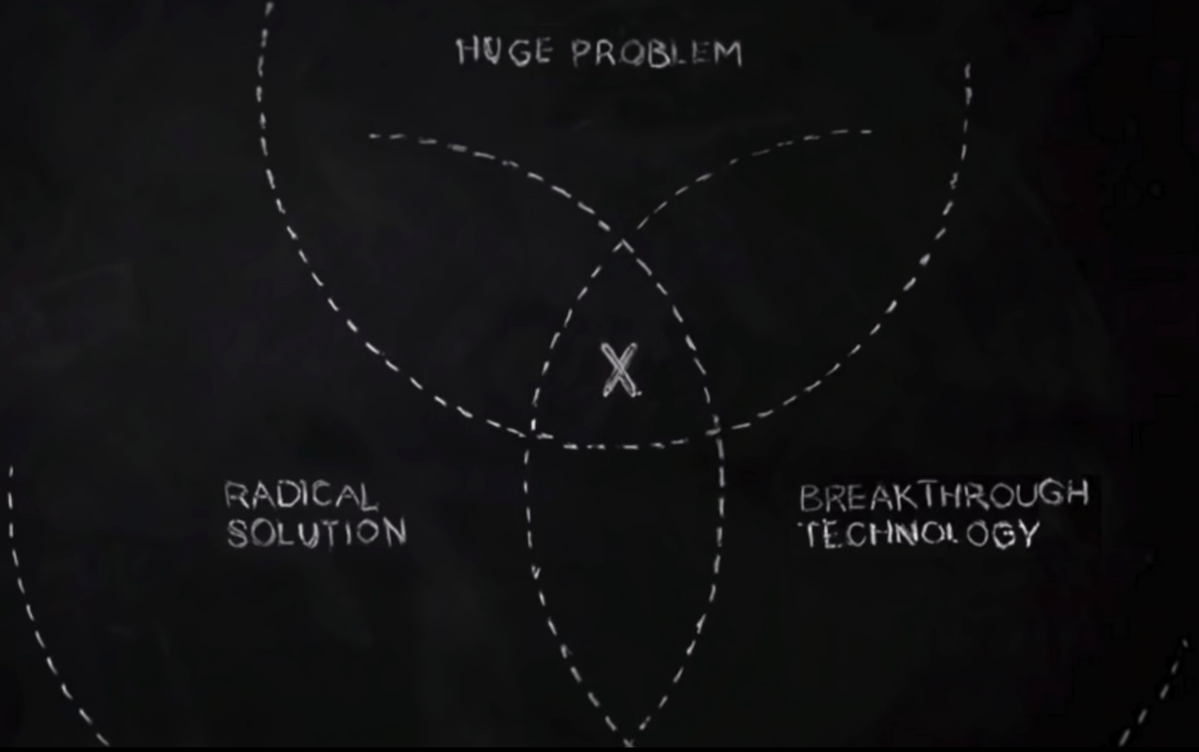

Moonshot Blueprint of X

In his 2016 Ted Talk, Teller discussed his blueprint for finding moonshots.

This is how he described their three-stage process:

- “Find a huge problem in the world that affects millions of people.”

- “We want to find a radical solution for solving that problem.”

- “There has to be some reason to believe that the technology for such a radical solution could actually be built.”

The real secret of X

The process seems easy. But in the same talk, Teller shared the secret: “We spend most of the time breaking things, trying to prove that we are wrong.” Later, he shared more details behind their decision-making process.

Imagine being asked to organise a show with monkeys standing on pedestals and reciting Shakespeare. How would you approach this project? Essentially, there are two critical parts of the project: one is having enough pedestals, and the second is teaching monkeys to recite Shakespeare. How would you allocate time between those two tasks?

The obvious way is to spend zero time on pedestals and try to teach the monkeys first because this is the most challenging part and potentially a bottleneck.

In real life, many people do the opposite. They start with low-hanging fruit first. It is natural to get the project going. It may also benefit you if your manager or customer regularly assesses you, and you must show some progress. The main issue is that it becomes much harder to abandon the project once you have spent considerable time, money and effort on low-hanging fruit opportunities (pedestals). Ultimately, your costs explode, but the actual result is not there.

Imagine being asked to organise a show with monkeys standing on pedestals and reciting Shakespeare. How would you approach this project? Essentially, there are two critical parts of the project: one is having enough pedestals, and the second is teaching monkeys to recite Shakespeare. How would you allocate time between those two tasks?

The obvious way is to spend zero time on pedestals and try to teach the monkeys first because this is the most challenging part and potentially a bottleneck.

In real life, many people do the opposite. They start with low-hanging fruit first. It is natural to get the project going. It may also benefit you if your manager or customer regularly assesses you, and you must show some progress. The main issue is that it becomes much harder to abandon the project once you have spent considerable time, money and effort on low-hanging fruit opportunities (pedestals). Ultimately, your costs explode, but the actual result is not there.

II. Bullet Train saga

Many infrastructure projects go through such problems. Earlier this year, I attended a three-week training by Annie Duke, one of the world’s leading experts on decision-making and one of the top poker players in the world. During one of our classes, we were asked to consider a new project for high-speed rail connecting two large cities in a small country. The two towns on opposite sides of the country accounted for about 80% of the country’s GDP. The only available ways to travel between the two cities were by air (about 1 hour) or car (about 6 hours). The new rail link would allow citizens to travel in about 2.5 hours, improve the connectivity of smaller towns located in the middle of the country, create new job opportunities and improve the environment (the train’s CO2 intensity is about 95% lower than that of the aeroplane and 91% lower than travelling by car).

It was estimated that the link would cost $33bn and take about ten years to complete. The project’s annual revenue was estimated at $1.3bn with an operating profit of $370mn (per year).

The students in Annie’s class were asked to decide whether the project should go ahead and, more specifically, should the authorities go ahead with the $9bn bond issue to fund the project’s first phase.

Using the “Monkeys & Pedestals” mental model, we tried to identify the “Monkeys” in this project. In other words, what was the most challenging part of completing the project, and try to solve it first before making the final commitment. The “Monkeys” turned out to be the mountains crossing the future route.

It was estimated that the link would cost $33bn and take about ten years to complete. The project’s annual revenue was estimated at $1.3bn with an operating profit of $370mn (per year).

The students in Annie’s class were asked to decide whether the project should go ahead and, more specifically, should the authorities go ahead with the $9bn bond issue to fund the project’s first phase.

Using the “Monkeys & Pedestals” mental model, we tried to identify the “Monkeys” in this project. In other words, what was the most challenging part of completing the project, and try to solve it first before making the final commitment. The “Monkeys” turned out to be the mountains crossing the future route.

In fact, the case study was based on the Bullet Train project meant to connect San Diego and Los Angeles in the South of California with Silicon Valley and San Francisco Bay.

The construction of the first 25 miles of track was approved in 2010; the works began in 2015. In 2018, the authorities admitted that “the Tehachapi Mountains and the Pacheco Pass present a high degree of engineering uncertainty”. By 2022, the total budget cost increased to over $105bn. The project is still not complete and generating zero revenue.

The construction of the first 25 miles of track was approved in 2010; the works began in 2015. In 2018, the authorities admitted that “the Tehachapi Mountains and the Pacheco Pass present a high degree of engineering uncertainty”. By 2022, the total budget cost increased to over $105bn. The project is still not complete and generating zero revenue.

III. What stops us from cutting losses early

If you, like me, have been investing in the stock market for some time, you can recall many situations when you wished you had sold the position early.

Don’t worry about past mistakes. Even Warren Buffett makes them and is not shy to admit them. Here is an excerpt from Buffett’s 2007 shareholder letter, for example:

Don’t worry about past mistakes. Even Warren Buffett makes them and is not shy to admit them. Here is an excerpt from Buffett’s 2007 shareholder letter, for example:

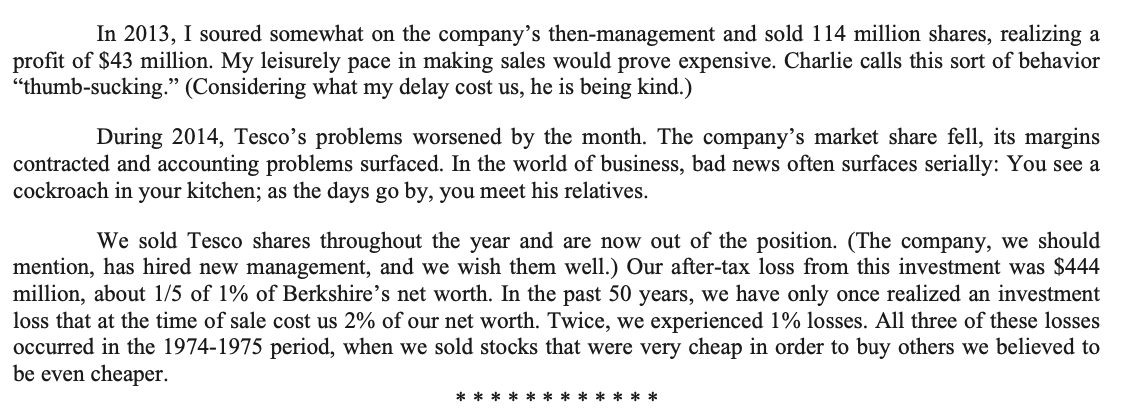

And this is how he described his experience with Tesco in a 2014 letter.

The issue is not that certain investments will go south. This is almost inevitable. The real problem is not recognising this early and, worse, pouring more resources into a losing position. When we receive negative signals about our investment, we often escalate our commitment. Just like the government facing delays and ballooning costs of the high-speed rail when it decides to invest even more money in the project.

Several cognitive biases prevent us from cutting losses early.

Several cognitive biases prevent us from cutting losses early.

- The most famous is the “Sunk cost fallacy”. We compare the historical costs already incurred (including time) with the remaining efforts and often decide to keep going. If we have done extensive research, met management, studied competitors, and built a huge financial model, abandoning such an investment is quite challenging.

- We also value more what we already own, called the “Endowment effect”. In various experiments during the early 1990s, Kahneman and Thaler discovered that students who were given mugs at the start of the class valued them more than those who did not.

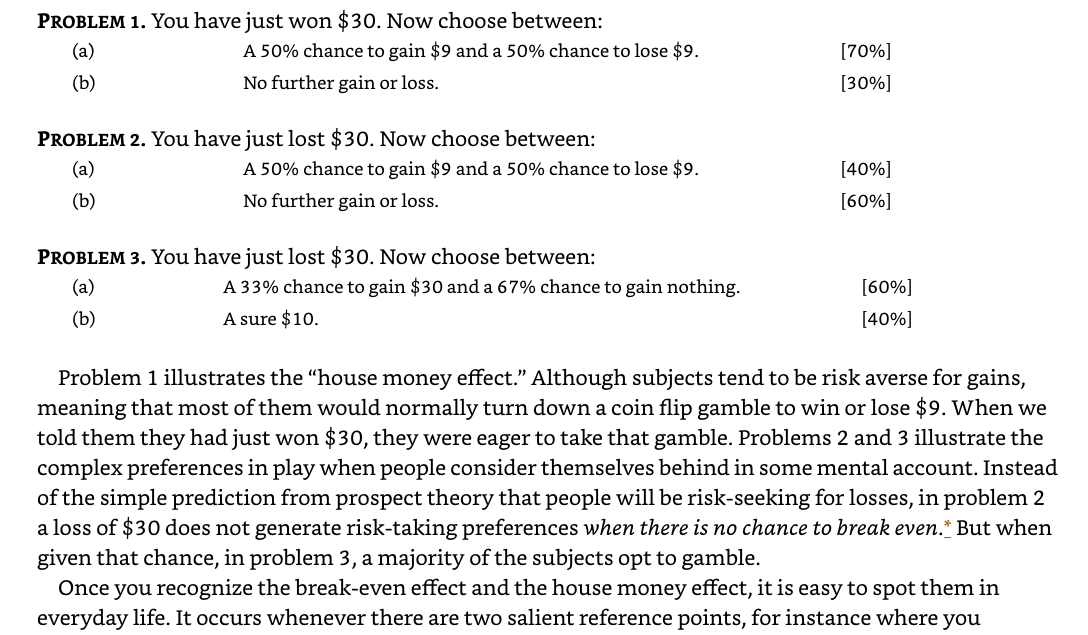

- “Loss aversion” bias makes a $1 loss “feel” almost twice as strong as $1 gain. As a result, we are afraid to “take losses” by selling an underperforming position, hoping it will break even eventually. In his book, Misbehaving, Richard Thaler also described a break-even bias which turns people into risk-seekers after losing money. He showed that more people were willing to take a bet to win $30 with a 33% chance (and 67% chance of getting zero) if they lost $30 compared to a bet of winning or losing $9 with an equal 50% chance. Below is an excerpt from Thaler:

- “Status quo” bias often comes together with the “Endowment effect” and generally makes people unwilling to change.

- “Omission bias” happens when people judge harm as a result of commission more negatively than harm due to omission. In investing, you feel worse when you lose $20 million by taking action (like buying a stock that goes down or selling an underperforming one). However, if you hold $100 million in a bank account with zero interest and do not invest in the stock market, most likely, you will give away $20 million of future returns (and probably more in the long-term), but this does not feel as bad.

Decision-making experts also refer to one more bias (“Optimism bias”) which stops us from quitting early, although I am less sure we have to be too worried about that one since there are probably more benefits from it than harm.

It is also hard to change your decision once you make it public. There is some social bias against people who change their minds and appear inconsistent. They are often viewed as unreliable. So-called experts, who often speak to the media, are particularly prone to this problem. They would seek all kinds of evidence to support their original view rather than admit they were wrong.

For many people being right is more important than making money.

Philip Tetlock and Dan Gardner have discussed this issue in detail in their book Superforecasting . They showed how little-known people made far superior forecasts than the world’s famous experts.

IV. Quitting can be the biggest secret of Warren Buffett

Patience and long-term focus are often viewed as the most significant virtues of Warren Buffett. His comments like “Our favourite holding period is forever” are probably the reason for such views.

Many people wrongly assume that his investment strategy boils down to finding select quality companies, buying them at a discount and holding them (almost) forever. Since there is no perfect information on how the business will perform in 5 or 10 years, and Buffett has to use his judgement just like everyone else, his strategy is actually a little different. In more recent letters, he compared Berkshire’s portfolio to a forest. This is what he wrote in his 2018 letter:

Many people wrongly assume that his investment strategy boils down to finding select quality companies, buying them at a discount and holding them (almost) forever. Since there is no perfect information on how the business will perform in 5 or 10 years, and Buffett has to use his judgement just like everyone else, his strategy is actually a little different. In more recent letters, he compared Berkshire’s portfolio to a forest. This is what he wrote in his 2018 letter:

In other words, Buffett admits that some of his holdings will be anything but successful investments.

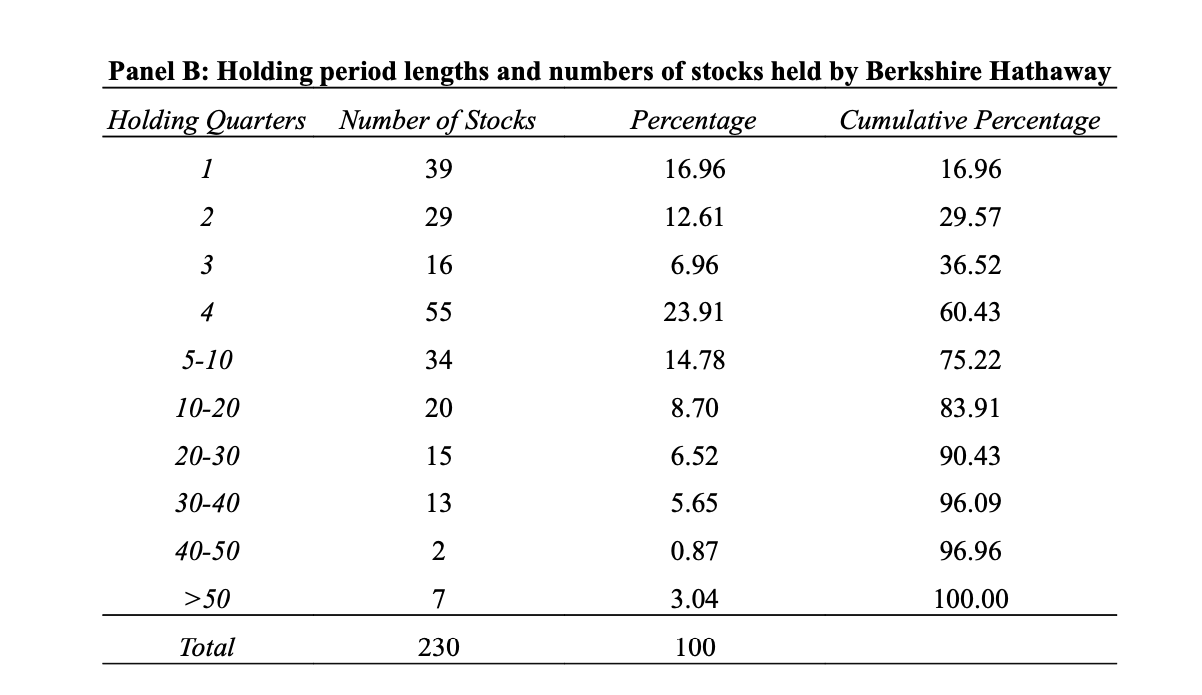

To my mind, his biggest secret is his ruthlessness in admitting mistakes early and exiting the positions. Before looking at the table below, try answering these two questions:

I guarantee you will be hugely surprised unless you have seen the study.

Take a look at the table below, which I borrowed from the 2010 study Overconfidence, Under-Reaction, and Warren Buffett’s Investments:

To my mind, his biggest secret is his ruthlessness in admitting mistakes early and exiting the positions. Before looking at the table below, try answering these two questions:

- How many stocks did Berkshire own during 1980-2006 (27 years)?

- What percentage of stocks Berkshire owned for less than one year (i.e. the share of stocks that Berkshire sold within a year after buying)?

I guarantee you will be hugely surprised unless you have seen the study.

Take a look at the table below, which I borrowed from the 2010 study Overconfidence, Under-Reaction, and Warren Buffett’s Investments:

Source: Overconfidence, Under-Reaction, and Warren Buffett’s Investments by J.Hughes, J.Liu, M.Zhang

Buffett owned 230 different stocks during 1980-2006, and over 60% of the stocks were sold within 12 months after buying! In other words, if Buffett buys a stock today, there is a 60% chance he will sell it within the next 12 months based on that historical data.

This is a great testament to his courage to admit mistakes early and sell rather than wait and hope. The problem of many young value investors is that they try to copy Buffett’s conviction by buying just a handful of stocks and then sitting on them, ignoring any new information. In fact, only the facts supporting the original buy decision often get through the filters to keep conviction strong and avoid changing one’s mind.

This is a great testament to his courage to admit mistakes early and sell rather than wait and hope. The problem of many young value investors is that they try to copy Buffett’s conviction by buying just a handful of stocks and then sitting on them, ignoring any new information. In fact, only the facts supporting the original buy decision often get through the filters to keep conviction strong and avoid changing one’s mind.

V. Four steps to cut losses early

“Every minute you spend on something that is not worthwhile is a minute you can’t spend on something that is worthwhile. That is the cost of the failure to cut your losses.”

- Annie Duke, former professional poker player and author in cognitive-behavioural decision science and decision education

So how can we get better at finding the balance between focusing on the long-term and ignoring the short-term noise, on the one hand, and reversing our decisions when the facts change?

There are four basic steps that you should take.

1. Monkeys and pedestals. Identify the hardest part of the project or what would make your decision succeed. Try to solve it first. When analysing a company, its financial position could be ”the monkey” to focus on. Suppose a company has a large debt repayment looming. In that case, before making long-term projections about the future demand for a company’s product, you should focus on whether it has enough cash flows and other funding options. This is just an example. Often, there is one or two critical factors in each case that you should focus on first before digging deep into other questions.

2. Pre-mortem. This is a crucial step which only some people take in reality. Imagine and then write down how your decision / investment has failed. Doing so would allow you to identify the things that can go wrong. You may realise the areas that you need to do additional research on. It would be best to become more aware of various risks and uncertainties. You should use this pre-mortem scenario to identify the early warning signals and develop your “Kill criteria”.

3. Kill criteria. Write down criteria that would lead you to exit the position before making an investment. Ideally, it should have a time factor and specific conditions. For example, suppose you are considering investing in a household brand that has recently lost market share. Your thesis is based on the idea that current weakness is temporary. In that case, you should set a time budget (e.g. 2-3 years) and a specific parameter (e.g. market share reaches 20% again) before you invest in the company. If the company fails to achieve the specified market share in three years, you sell the position.

4. Find a friend who could challenge your decisions and provide an outside view. Warren Buffett likes to praise his long-term partner, Charlie Munger. A good friend can give critical feedback to help you quit your decision faster. When dealing with a situation alone, we are often influenced by various biases. We pay too much attention to a narrow group of factors that are relevant to this particular case. However, a friend can take a fresh look and consider other factors that you have missed. You need to trust your friend and be willing to receive candid feedback, even if, at times, it sounds like unpleasant criticism. Just imagining yourself in a position of a friend and giving advice about a complex situation can already help.

There are four basic steps that you should take.

1. Monkeys and pedestals. Identify the hardest part of the project or what would make your decision succeed. Try to solve it first. When analysing a company, its financial position could be ”the monkey” to focus on. Suppose a company has a large debt repayment looming. In that case, before making long-term projections about the future demand for a company’s product, you should focus on whether it has enough cash flows and other funding options. This is just an example. Often, there is one or two critical factors in each case that you should focus on first before digging deep into other questions.

2. Pre-mortem. This is a crucial step which only some people take in reality. Imagine and then write down how your decision / investment has failed. Doing so would allow you to identify the things that can go wrong. You may realise the areas that you need to do additional research on. It would be best to become more aware of various risks and uncertainties. You should use this pre-mortem scenario to identify the early warning signals and develop your “Kill criteria”.

3. Kill criteria. Write down criteria that would lead you to exit the position before making an investment. Ideally, it should have a time factor and specific conditions. For example, suppose you are considering investing in a household brand that has recently lost market share. Your thesis is based on the idea that current weakness is temporary. In that case, you should set a time budget (e.g. 2-3 years) and a specific parameter (e.g. market share reaches 20% again) before you invest in the company. If the company fails to achieve the specified market share in three years, you sell the position.

4. Find a friend who could challenge your decisions and provide an outside view. Warren Buffett likes to praise his long-term partner, Charlie Munger. A good friend can give critical feedback to help you quit your decision faster. When dealing with a situation alone, we are often influenced by various biases. We pay too much attention to a narrow group of factors that are relevant to this particular case. However, a friend can take a fresh look and consider other factors that you have missed. You need to trust your friend and be willing to receive candid feedback, even if, at times, it sounds like unpleasant criticism. Just imagining yourself in a position of a friend and giving advice about a complex situation can already help.

VI. How I started implementing this technique in practice

I recently wrote about my decision to sell EPAM. While I have not written a full pre-mortem or spoken to a trusted friend, I have developed my “Kill” criteria early on. Since I initially viewed EPAM as a “quality and fast-growing business that should not be affected by the Russian-Ukraine war, “ the moment the company appeared to be slowing down made me revisit my case. The fact that EPAM was still trading as a high-growth company while, in reality, it was struggling to grow this year made me exit the position.

Altria is another example. I initially bought it because of its exceptional market position (close to 50% market share in the US) and undemanding valuation (high single PE and c. 8% dividend yield). The core part of my thesis was that with such strong market positions, the company should have had strong pricing power, which should help it during economic recessions. However, each time the US economy showed some weakness, Altria was losing market share as customers were switching to cheaper alternatives. Besides, the company is way behind its peers in transitioning to non-combustible products (like Philip Morris’s IQOS). I have not sold my position completely, but I have been reducing it since last year.

Altria is another example. I initially bought it because of its exceptional market position (close to 50% market share in the US) and undemanding valuation (high single PE and c. 8% dividend yield). The core part of my thesis was that with such strong market positions, the company should have had strong pricing power, which should help it during economic recessions. However, each time the US economy showed some weakness, Altria was losing market share as customers were switching to cheaper alternatives. Besides, the company is way behind its peers in transitioning to non-combustible products (like Philip Morris’s IQOS). I have not sold my position completely, but I have been reducing it since last year.

Did you find this article helpful? If you want to read my next article right when it comes out, please subscribe to my email list.