2 March 2025

Each time Berkshire releases its financials, there is no lack of commentary on its performance. The usual conclusion is that Berkshire is a solid business with an excellent track record but is now close to being fully valued and, consequently, offers little upside at current prices.

Having been a shareholder since 2007, I would like to offer a different perspective on the company and the lessons investors can take from it.

Having been a shareholder since 2007, I would like to offer a different perspective on the company and the lessons investors can take from it.

Why so many investors don’t like Berkshire as an investment?

Berkshire Hathaway has one of the best long-term investment track records in history. It is also a relatively simple business that does not require investors to make long-term guesses (e.g., who will win the next technological revolution or how macro policy will change in EM).

It is hard to beat Berkshire on costs. Its headquarters staff consists of about 25 people, and the CEO receives an annual salary of $100,000 (no bonuses).

Buffett, the CEO of Berkshire Hathaway, has been open about his strategy and business throughout the past six decades. He is also the largest shareholder, with proper “skin in the game.”

In other words, Berkshire is a simple investment that is available to everyone.

Yet, so many investors have missed it. This is not a post on why you should own Berkshire Hathaway. Rather, it is about the reasons holding people back from investing in Berkshire and the lessons we can learn from it. These lessons are particularly valuable since many earn less than 10% annually throughout their investment journey. What is readily available (market average returns) is somehow lost at the individual level.

Of course, the five lessons below are not a complete list.

It is hard to beat Berkshire on costs. Its headquarters staff consists of about 25 people, and the CEO receives an annual salary of $100,000 (no bonuses).

Buffett, the CEO of Berkshire Hathaway, has been open about his strategy and business throughout the past six decades. He is also the largest shareholder, with proper “skin in the game.”

In other words, Berkshire is a simple investment that is available to everyone.

Yet, so many investors have missed it. This is not a post on why you should own Berkshire Hathaway. Rather, it is about the reasons holding people back from investing in Berkshire and the lessons we can learn from it. These lessons are particularly valuable since many earn less than 10% annually throughout their investment journey. What is readily available (market average returns) is somehow lost at the individual level.

Of course, the five lessons below are not a complete list.

Lesson 1: Price Targets add little value

Many commentators like to assign a fair value to Berkshire’s shares. Usually, they apply a multiple to operating income and then add the market value of securities and net cash.

The decision to buy or sell Berkshire Hathaway shares then turns into a call on whether their market price is above or below the assessed value. In most cases, the upside (calculated as the difference between a theoretically estimated price and the market price) is too small to justify buying the shares.

And so people turn away in search of stocks with more upside.

I have been a shareholder in Berkshire since 2007, and I, too, used to estimate its fair value. Eventually, I realised this approach had too many shortcomings and switched to a better method.

First, earnings in any year depend on several cyclical factors. A business is worth the discounted value of all the cash flow it generates over its lifetime. By taking the most recent earnings, we anchor our estimates to a particular set of circumstances.

Secondly, the multiple we use cannot be more subjective. We can look at comparable valuation, but it provides little value.

A well-trained analyst can estimate a range of values by tweaking discount rates, long-term growth, margins, target multiples and other parameters. Soon, a single price estimate transforms into several dozen price points. With numbers at hand, an investor feels more prepared and confident, but arguably, they just have become more clueless.

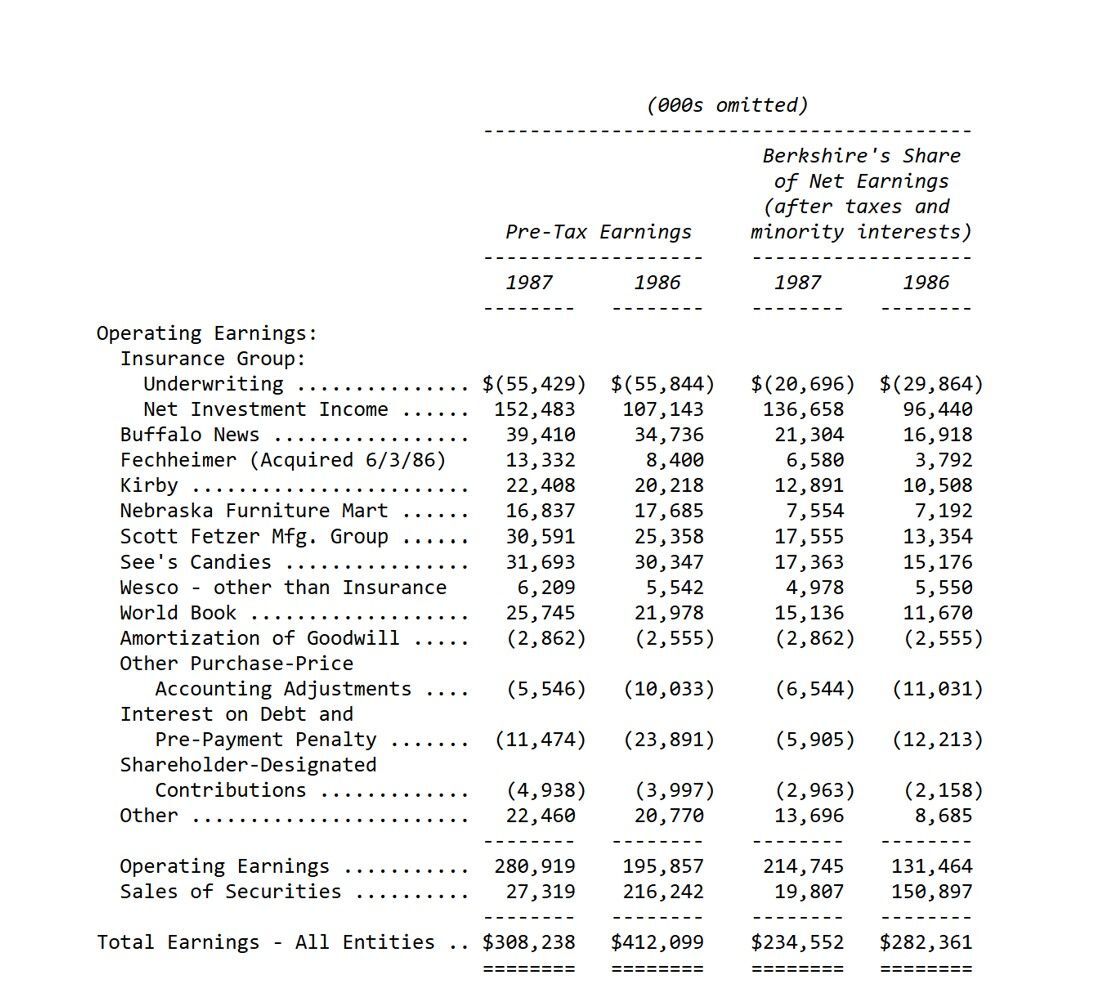

Imagine you had to estimate Berkshire’s value in 1987. Here is a snapshot from Warren Buffett’s annual letter.

The decision to buy or sell Berkshire Hathaway shares then turns into a call on whether their market price is above or below the assessed value. In most cases, the upside (calculated as the difference between a theoretically estimated price and the market price) is too small to justify buying the shares.

And so people turn away in search of stocks with more upside.

I have been a shareholder in Berkshire since 2007, and I, too, used to estimate its fair value. Eventually, I realised this approach had too many shortcomings and switched to a better method.

First, earnings in any year depend on several cyclical factors. A business is worth the discounted value of all the cash flow it generates over its lifetime. By taking the most recent earnings, we anchor our estimates to a particular set of circumstances.

Secondly, the multiple we use cannot be more subjective. We can look at comparable valuation, but it provides little value.

A well-trained analyst can estimate a range of values by tweaking discount rates, long-term growth, margins, target multiples and other parameters. Soon, a single price estimate transforms into several dozen price points. With numbers at hand, an investor feels more prepared and confident, but arguably, they just have become more clueless.

Imagine you had to estimate Berkshire’s value in 1987. Here is a snapshot from Warren Buffett’s annual letter.

Source: Berkshire Hathaway Letter to Shareholders 1987

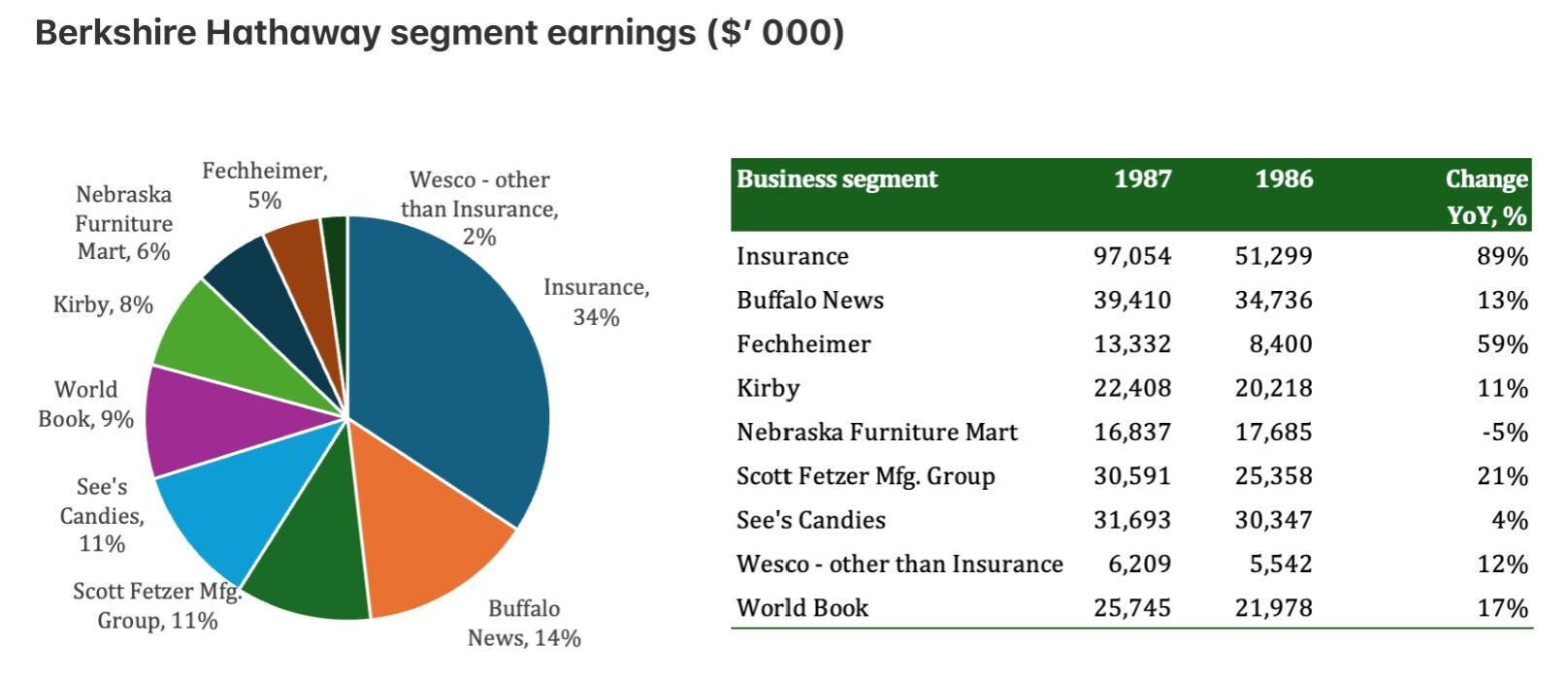

The insurance segment contributed 34% of the total earnings, followed by Buffalo News (14%), Scott Fetzer (11%), and See’s Candies (11%). While some businesses offered promising returns on capital, margins, and growth, none stood out as true champions. Notably, none of the companies provided groundbreaking solutions or innovative products.

Source: Berkshire Hathaway Letter to Shareholders 1987, Hidden Value Gems

Applying an “average” 15x P/E multiple to Berkshire’s $280.9mn pre-tax operating earnings in 1987 would have yielded a fair value estimate of $4.2bn ($3,661 per Class A share). The actual stock price was $2,915 on 2 January 1987, peaking at $4,220 in September, then crashing to $2,675 on 27 October and finishing the year at $2,950.

How could this assessment of the fair value have helped investors? Would it have indicated a 37% upside when the stock was at a year’s low in October? Or should investors have lowered their “fair multiple” to reflect broader market risks and lower valuation of “comparable” companies?

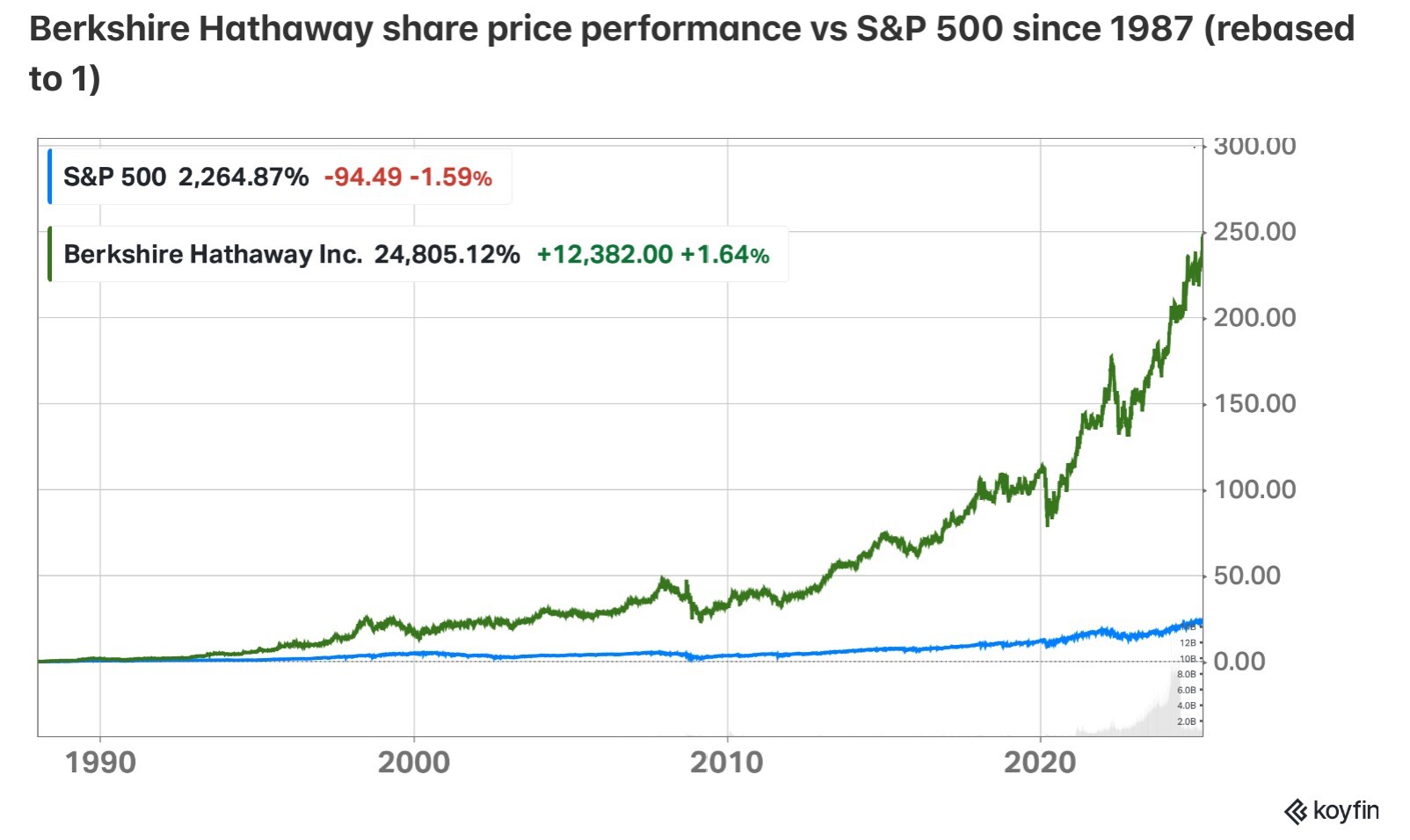

It would help to note that since the end of 1987, Berkshire’s share price has increased by about 255x, or at a compound annual rate of c. 16%.

Estimates made back in 1987 were useless to someone prepared to wait unless an investor had personal reasons to sell to meet near-term financial goals in that particular year.

How could this assessment of the fair value have helped investors? Would it have indicated a 37% upside when the stock was at a year’s low in October? Or should investors have lowered their “fair multiple” to reflect broader market risks and lower valuation of “comparable” companies?

It would help to note that since the end of 1987, Berkshire’s share price has increased by about 255x, or at a compound annual rate of c. 16%.

Estimates made back in 1987 were useless to someone prepared to wait unless an investor had personal reasons to sell to meet near-term financial goals in that particular year.

Source: Koyfin

So, what is a better method then?

Personally, I have switched from estimating upside in a particular stock to potential returns. A stock upside is the difference between the theoretical value of a stock and its current price.

Potential returns, on the other hand, indicate at what rate a business can increase its net worth. The best place to start is to assume you are buying 100% of the company and the stock market closes the next day forever. You cannot sell a single share on the stock exchange. How would you estimate your returns? The most natural way would be to calculate the change in normalised earnings over time, adjusted for the share count. This change would correspond with the returns on capital of the underlying business.

Using this approach, it could have been easier to identify Berkshire as a promising investment and hold it for much longer, benefiting from the power of compounding.

Personally, I have switched from estimating upside in a particular stock to potential returns. A stock upside is the difference between the theoretical value of a stock and its current price.

Potential returns, on the other hand, indicate at what rate a business can increase its net worth. The best place to start is to assume you are buying 100% of the company and the stock market closes the next day forever. You cannot sell a single share on the stock exchange. How would you estimate your returns? The most natural way would be to calculate the change in normalised earnings over time, adjusted for the share count. This change would correspond with the returns on capital of the underlying business.

Using this approach, it could have been easier to identify Berkshire as a promising investment and hold it for much longer, benefiting from the power of compounding.

Lesson 2: It is all about good businesses

Returns on capital are closely associated with the quality of the business, its margins and capital requirements. If a company can sell products at a premium to competitors or produce goods at a lower cost, it is likely due to a competitive advantage. What are the sources, and even more important, how sustainable is this competitive advantage? This is a critical question every investor should try to understand.

Good businesses usually, although not always, have “exceptional” financial performance. However, financial analysis alone is not sufficient, as financials are always backward-looking.

It is the analysis of the product, customers, suppliers, the broader industry, and other factors (e.g., regulation) that can properly help one understand the business as an investment opportunity.

As Buffett says,

Good businesses usually, although not always, have “exceptional” financial performance. However, financial analysis alone is not sufficient, as financials are always backward-looking.

It is the analysis of the product, customers, suppliers, the broader industry, and other factors (e.g., regulation) that can properly help one understand the business as an investment opportunity.

As Buffett says,

I am a better investor because I am a businessman and a better businessman because I am an investor.

Peter Lynch also made this point:

Often there is no correlation between the success of a company's operations and the success of its stock over a few months or even years. In the long term, there is a 100% correlation… it pays to be patient, and to own successful companies.

Lesson 3: Don’t confuse the virtue of patience

One of the first qualities aspiring value investors look to emulate is patience. However, patience only benefits those invested in excellent businesses. Patience with owning “a melting ice cube” will only lead to more significant losses, regardless of how low the initial valuation multiple is.

Patience is needed to continue owning a quality business and ignoring short-term “noise.” Almost every day, I see a headline about the Fed’s potential next move and what a new piece of macro data means for the likelihood of a rate hike or cut. Imagine you bought Berkshire shares in 1987. How relevant would this information have been to you in your investment journey? Most likely, it would have been harmful.

But it is actually more complicated than just ignoring “noise”. Holding Berkshire shares also means not being afraid of looking dumb or lazy. I have experienced this firsthand. I attended a few investor conferences last year. Talking about your favourite stock during coffee breaks and other socialising opportunities is common. Almost every time I mentioned Berkshire as my largest position, I noticed how I made the other side surprised and even disappointed.

I can see why. If you manage other people’s money and Berkshire is your most prominent position, how can you justify the fees you charge your clients?

Instead of “turning thousands of rocks” in search of the next gem, you essentially outsourced your stock picking to an old man whose company got so big that a stock outside the Top 100 list is too small to move the needle for them.

Besides, it is so well-known. What is your edge (or alpha, using the jargon)? After all, you don’t need to be smart or hold the CFA designation to invest in Berkshire.

Moreover, Buffett has stressed risk minimisation so frequently that Berkshire is often seen as a retiree's portfolio. Even with grey hair, my peers could see I was not old enough to be “that cautious”.

Of course, there are specific reasons I liked Berkshire recently (in the last few years), such as higher inflation, which benefited their insurance operations and railways, or higher power demand and energy prices (a boost to BHE). But the general point remains the same. It is hard to stand out if you hold Berkshire Hathaway.

Lastly, there are always reasons to “trim” your position in Berkshire. Just recently (19 September 2024), an investor posted a short thesis on Berkshire Hathaway on the Value Investors Club. The thesis argued that Berkshire’s assets are not exceptional, and with Buffett’s ageing, the stock will struggle to trade at a premium valuation. Since that post, Berkshire has gained 11.7% (the S&P500 is +4.2%).

A week before that post, Ajit Jain, Berkshire’s Vice Chairman, cut his holding in the company by 55%. Insider selling is occasionally a reason to start worrying. But investors who ignored this have done well so far.

Holding Berkshire throughout the years has not been easy psychologically.

One of the most common pushbacks I heard was, “The stock will drop when Buffett is no longer there.” I heard several variations of this question asked at Berkshire’s annual meetings. As far as I remember, this question was first asked in the 1990s. (Don’t worry; I was too young and not rich enough to attend that meeting; I just watched the recording a few years ago.)

The point is that there is always something to worry about.

However, the composition of Berkshire’s assets, as well as the two other factors (see below), provides a strong foundation for generating 10-15% returns over the long term, meaning patience would probably continue to pay off. The following two lessons help explain the sources of those potential returns.

Patience is needed to continue owning a quality business and ignoring short-term “noise.” Almost every day, I see a headline about the Fed’s potential next move and what a new piece of macro data means for the likelihood of a rate hike or cut. Imagine you bought Berkshire shares in 1987. How relevant would this information have been to you in your investment journey? Most likely, it would have been harmful.

But it is actually more complicated than just ignoring “noise”. Holding Berkshire shares also means not being afraid of looking dumb or lazy. I have experienced this firsthand. I attended a few investor conferences last year. Talking about your favourite stock during coffee breaks and other socialising opportunities is common. Almost every time I mentioned Berkshire as my largest position, I noticed how I made the other side surprised and even disappointed.

I can see why. If you manage other people’s money and Berkshire is your most prominent position, how can you justify the fees you charge your clients?

Instead of “turning thousands of rocks” in search of the next gem, you essentially outsourced your stock picking to an old man whose company got so big that a stock outside the Top 100 list is too small to move the needle for them.

Besides, it is so well-known. What is your edge (or alpha, using the jargon)? After all, you don’t need to be smart or hold the CFA designation to invest in Berkshire.

Moreover, Buffett has stressed risk minimisation so frequently that Berkshire is often seen as a retiree's portfolio. Even with grey hair, my peers could see I was not old enough to be “that cautious”.

Of course, there are specific reasons I liked Berkshire recently (in the last few years), such as higher inflation, which benefited their insurance operations and railways, or higher power demand and energy prices (a boost to BHE). But the general point remains the same. It is hard to stand out if you hold Berkshire Hathaway.

Lastly, there are always reasons to “trim” your position in Berkshire. Just recently (19 September 2024), an investor posted a short thesis on Berkshire Hathaway on the Value Investors Club. The thesis argued that Berkshire’s assets are not exceptional, and with Buffett’s ageing, the stock will struggle to trade at a premium valuation. Since that post, Berkshire has gained 11.7% (the S&P500 is +4.2%).

A week before that post, Ajit Jain, Berkshire’s Vice Chairman, cut his holding in the company by 55%. Insider selling is occasionally a reason to start worrying. But investors who ignored this have done well so far.

Holding Berkshire throughout the years has not been easy psychologically.

One of the most common pushbacks I heard was, “The stock will drop when Buffett is no longer there.” I heard several variations of this question asked at Berkshire’s annual meetings. As far as I remember, this question was first asked in the 1990s. (Don’t worry; I was too young and not rich enough to attend that meeting; I just watched the recording a few years ago.)

The point is that there is always something to worry about.

However, the composition of Berkshire’s assets, as well as the two other factors (see below), provides a strong foundation for generating 10-15% returns over the long term, meaning patience would probably continue to pay off. The following two lessons help explain the sources of those potential returns.

Lesson 3: Capital allocation is critical and often undervalued

Unlike profit margin or Price-to-Earnings valuation, capital allocation is not an easily quantifiable parameter. Over time, it reflects management’s decision-making skills about each additional dollar it earns. Should it (1) be invested back in the business, (2) spent on paying back debt, (3) used to fund a new business acquisition, or (4) distributed to shareholders via dividends or buyback?

Berkshire Hathaway’s history is a great case study on the importance of capital allocation.

In Buffett’s 1987 letter that I have already referred to earlier, Buffett makes a point that “a CEO whose company annually retains earnings equal to 10% of net worth will have been responsible for the deployment of more than 60% of all the capital at work in the business.”

Here is a visual example.

Berkshire Hathaway’s history is a great case study on the importance of capital allocation.

In Buffett’s 1987 letter that I have already referred to earlier, Buffett makes a point that “a CEO whose company annually retains earnings equal to 10% of net worth will have been responsible for the deployment of more than 60% of all the capital at work in the business.”

Here is a visual example.

Source: Hidden Value Gems

CEOs often have specific skills in areas such as sales, marketing, product development, or finance but have little experience allocating capital.

Sometimes, the issue is the incentive policy or general corporate culture. The latter is probably the most “intangible asset” in any business, yet it is an extremely important factor rarely considered in traditional financial research.

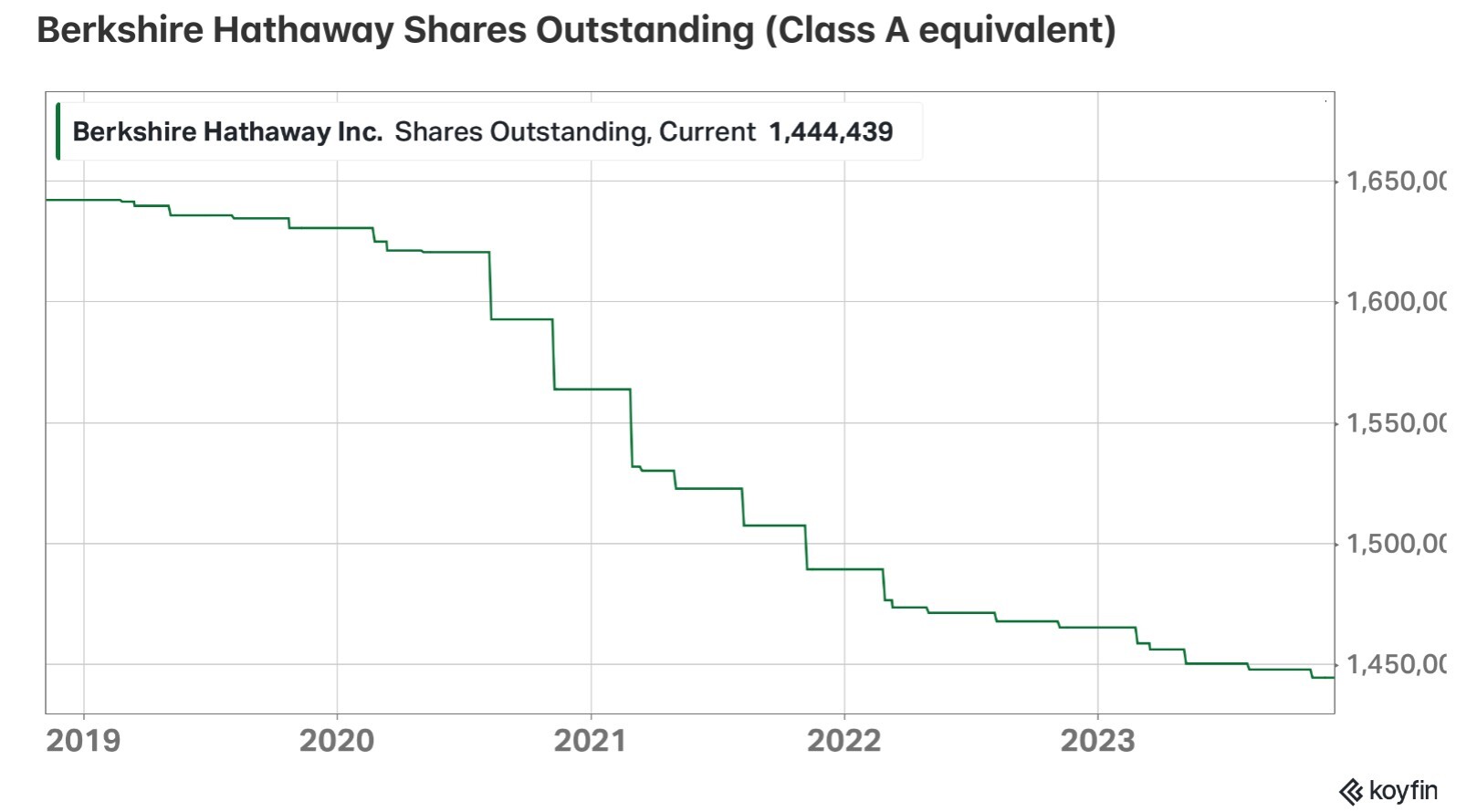

Berkshire started actively buying back its stock in 2020 and has since reduced its share count by c. 13%, buying more shares at lower prices. As share price has increased, the buyback activity has slowed. This activity alone adds value and, since it cannot be automated, largely depends on how well the CEO understands the intrinsic value and its drivers.

Sometimes, the issue is the incentive policy or general corporate culture. The latter is probably the most “intangible asset” in any business, yet it is an extremely important factor rarely considered in traditional financial research.

Berkshire started actively buying back its stock in 2020 and has since reduced its share count by c. 13%, buying more shares at lower prices. As share price has increased, the buyback activity has slowed. This activity alone adds value and, since it cannot be automated, largely depends on how well the CEO understands the intrinsic value and its drivers.

Source: Koyfin

Understanding a company’s capital allocation better can help one own it longer and benefit from the power of compounding.

Lesson 4: Stick with good people

This is self-explanatory, but I am still surprised each time I see what exceptional managers, often founders, have achieved over many years. There is clearly some survivorship bias, as they do not write many books about the thousands of failures experienced by equally capable entrepreneurs.

One specific point about “good people” is that how managers run the business is perhaps even more important than their professional qualifications. What always puts me off from investing in oil rig businesses, for example, is that management (and occasionally founders) are eager to raise third-party capital and rarely put enough of their own money directly in the business.

The opposite situations are usually more attractive.

One specific point about “good people” is that how managers run the business is perhaps even more important than their professional qualifications. What always puts me off from investing in oil rig businesses, for example, is that management (and occasionally founders) are eager to raise third-party capital and rarely put enough of their own money directly in the business.

The opposite situations are usually more attractive.

Lesson 5: Insurance

The insurance business is closely related to the art and skill of capital allocation. An insurance company gets paid immediately each time it sells a new insurance policy. However, the actual cost of that policy and the final profit have been unknown for a long time. These upfront payments create a ‘float’ that management can invest to generate extra income.

This industry favours cautious management with a long-term approach. Management’s direct ownership of insurance operations usually ensures this long-term view and proper risk policy. Berkshire Hathaway is one such example.

The most crucial point on insurance is that it is an integral part of Berkshire’s operations. Berkshire is not stuck with fixed-income, long-dated securities, unlike most other insurers. It invests the insurance float in equities that tend to rise over the long term. Few companies can afford it because they will be short of capital in the event of a major catastrophe (equities can go up or down, while private business may take a long time to sell).

Even if Berkshire sold insurance policies “at cost” (meaning that it had to pay policyholders all the premium it had collected back as insurance coverage), it would have still made money from returns on its equity portfolio. The longer the payback date, the better the results due to the compounding effect.

Luckily, Berkshire’s insurance operations have been profitable even without the income from the float. Its underwriting profit (policy price minus claims and admin costs) has averaged 3.3% over the past two decades, as Buffett noted in his latest shareholder letter:

This industry favours cautious management with a long-term approach. Management’s direct ownership of insurance operations usually ensures this long-term view and proper risk policy. Berkshire Hathaway is one such example.

The most crucial point on insurance is that it is an integral part of Berkshire’s operations. Berkshire is not stuck with fixed-income, long-dated securities, unlike most other insurers. It invests the insurance float in equities that tend to rise over the long term. Few companies can afford it because they will be short of capital in the event of a major catastrophe (equities can go up or down, while private business may take a long time to sell).

Even if Berkshire sold insurance policies “at cost” (meaning that it had to pay policyholders all the premium it had collected back as insurance coverage), it would have still made money from returns on its equity portfolio. The longer the payback date, the better the results due to the compounding effect.

Luckily, Berkshire’s insurance operations have been profitable even without the income from the float. Its underwriting profit (policy price minus claims and admin costs) has averaged 3.3% over the past two decades, as Buffett noted in his latest shareholder letter:

Over the past two decades, our insurance business has generated $32 billion of after-tax profits from underwriting, about 3.3 cents per dollar of sales after income tax. Meanwhile, our float has grown from $46 billion to $171 billion.

When analysts estimate the fair value of Berkshire’s insurance operations, they usually apply a market-based multiple to its insurance earnings or book value. However, this approach underestimates insurance’s crucial role in the overall business.

Because of this “permanent capital,” Buffett and his team can seek new acquisitions and, even more importantly, take advantage of occasional market dislocations by providing capital to companies in need on highly favourable terms. This inherent advantage does not boost earnings every year but eventually leads to above-market growth of intrinsic value.

Without the insurance operations, Berkshire’s capital allocation skills would not have created so much value over time.

A float is technically reflected as a liability on the balance sheet and, hence, has to be deducted from the enterprise value when estimating the equity value. However, in Berkshire’s case, the float generated positive returns as it was invested in high-return businesses, and overall payments on insurance claims were lower than the total premiums collected.

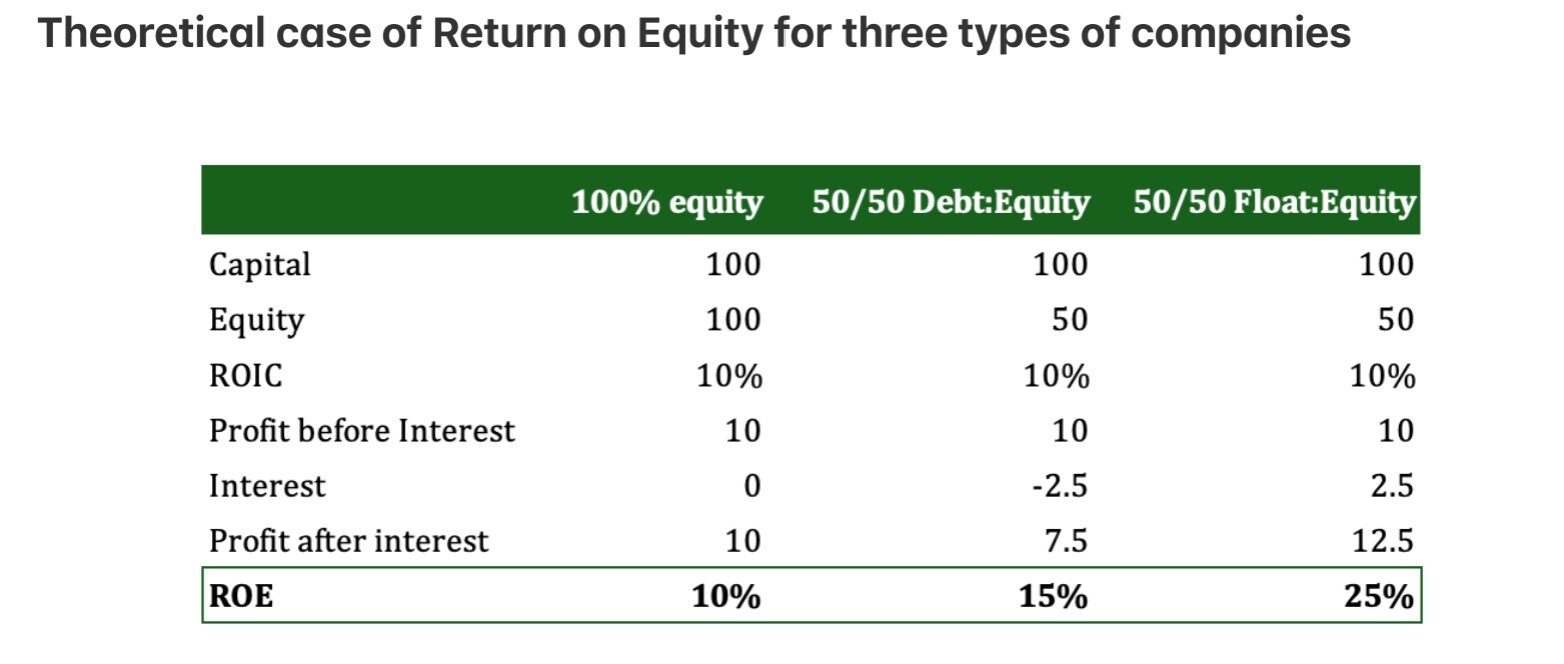

Below is a simple illustration of the difference in Returns on Equity for three types of companies in the same sector. If all of them earn 10% on their total capital, but they fund their operations differently, their ultimate ROE will differ materially. A company that only relies on its own capital would generate the same ROE as its ROIC (10%). A company that borrows will earn lower profits after interest, but utilising lower equity in its capital structure, it can achieve a higher ROE (15%). The best result is achieved by a company that can “borrow” and earn on its “borrowings”. This is similar to Berkshire Hathaway, although, of course, this is not a guaranteed outcome or in any way a precise estimate of its returns.

Because of this “permanent capital,” Buffett and his team can seek new acquisitions and, even more importantly, take advantage of occasional market dislocations by providing capital to companies in need on highly favourable terms. This inherent advantage does not boost earnings every year but eventually leads to above-market growth of intrinsic value.

Without the insurance operations, Berkshire’s capital allocation skills would not have created so much value over time.

A float is technically reflected as a liability on the balance sheet and, hence, has to be deducted from the enterprise value when estimating the equity value. However, in Berkshire’s case, the float generated positive returns as it was invested in high-return businesses, and overall payments on insurance claims were lower than the total premiums collected.

Below is a simple illustration of the difference in Returns on Equity for three types of companies in the same sector. If all of them earn 10% on their total capital, but they fund their operations differently, their ultimate ROE will differ materially. A company that only relies on its own capital would generate the same ROE as its ROIC (10%). A company that borrows will earn lower profits after interest, but utilising lower equity in its capital structure, it can achieve a higher ROE (15%). The best result is achieved by a company that can “borrow” and earn on its “borrowings”. This is similar to Berkshire Hathaway, although, of course, this is not a guaranteed outcome or in any way a precise estimate of its returns.

Source: Hidden Value Gems

Berkshire’s size and the strength of its balance sheet put it in a unique position. As Buffett says,

No private insurer is willing to take on the amount of risk that Berkshire can provide.

Besides, the company does not need to pass risks to reinsurers, providing an additional cost advantage.

This quality should remain even when Buffett no longer runs the company.

This quality should remain even when Buffett no longer runs the company.

Conclusion

Berkshire Hathaway is a unique business that will likely retain most of its qualities over the next few decades, if not longer. With underlying businesses generating 10% incremental returns or higher and having durable competitive advantages, the company can generate up to 15% shareholder returns as it benefits from the negative cost of the insurance float.

No one knows where its stock will be in one year. Moreover, after a strong performance, it is natural to expect some investors to take profits.

Having said that, there is always a place for Berkshire in my personal portfolio, which I manage with a 10-to 20-year view. With ample cash resources and exceptional capital allocation skills, Berkshire is particularly valuable in times of increased uncertainty and high asset valuations, like today. This is, of course, just my personal view and not investment advice.

As for broader investing, my big takeaway is not to stick to specific price targets but to spend time understanding the sources of business returns and the nature of the company’s competitive advantage. Do not underestimate the role of management, especially in allocating capital over the long term.

At the end of the day, what has helped Berkshire investors to reap extraordinary results throughout the past several decades was not their fascination with individual companies within Berkshire’s portfolio, but rather their conviction in Warren Buffett’s skills and integrity and that the method he was applying was better than average.

Betting on good people running good businesses can sometimes deliver extraordinary results.

No one knows where its stock will be in one year. Moreover, after a strong performance, it is natural to expect some investors to take profits.

Having said that, there is always a place for Berkshire in my personal portfolio, which I manage with a 10-to 20-year view. With ample cash resources and exceptional capital allocation skills, Berkshire is particularly valuable in times of increased uncertainty and high asset valuations, like today. This is, of course, just my personal view and not investment advice.

As for broader investing, my big takeaway is not to stick to specific price targets but to spend time understanding the sources of business returns and the nature of the company’s competitive advantage. Do not underestimate the role of management, especially in allocating capital over the long term.

At the end of the day, what has helped Berkshire investors to reap extraordinary results throughout the past several decades was not their fascination with individual companies within Berkshire’s portfolio, but rather their conviction in Warren Buffett’s skills and integrity and that the method he was applying was better than average.

Betting on good people running good businesses can sometimes deliver extraordinary results.

Further Reading

- Best industry for building wealth? (12 November 2023)

- Berkshire Hathaway: unique business at a discount price (29 August 2021)

- 7 Lessons from Omaha (2024 Edition) (5 May 2024)