5 May 2024

The first weekend of May is when value investors from around the world come to Omaha, Nebraska, the Midwestern city. On my way to Omaha, I thought about the most important lessons from Warren Buffett and Berkshire Hathaway that made the biggest impact on my investment performance. Here are the seven ideas that came to mind. I am curious about what you think, so feel free to leave a comment at the end of this article.

Lesson 1: Punchcard investing

“I could improve your ultimate financial welfare by giving you a ticket with only 20 slots in it, so that you had 20 punches — representing all the investments that you got to make in a lifetime. And once you’d punch through the card, you couldn’t make any more investments at all.”

- Warren Buffett

To me, this is the most powerful concept. Imagining that you can only make 20 investments for the rest of your life forces you to be much more careful and diligent before making your first purchase. It automatically slows you down and shifts your focus from short-term to long-term and from noise to more substantial things.

Is there still an upside in AI-related stocks? Will Trump’s victory crash markets? Will there be a military conflict between China and Taiwan? Will the FED cut interests this year?

Don’t get more wrong. All these developments impact markets. If rates fall, stocks will get a boost.

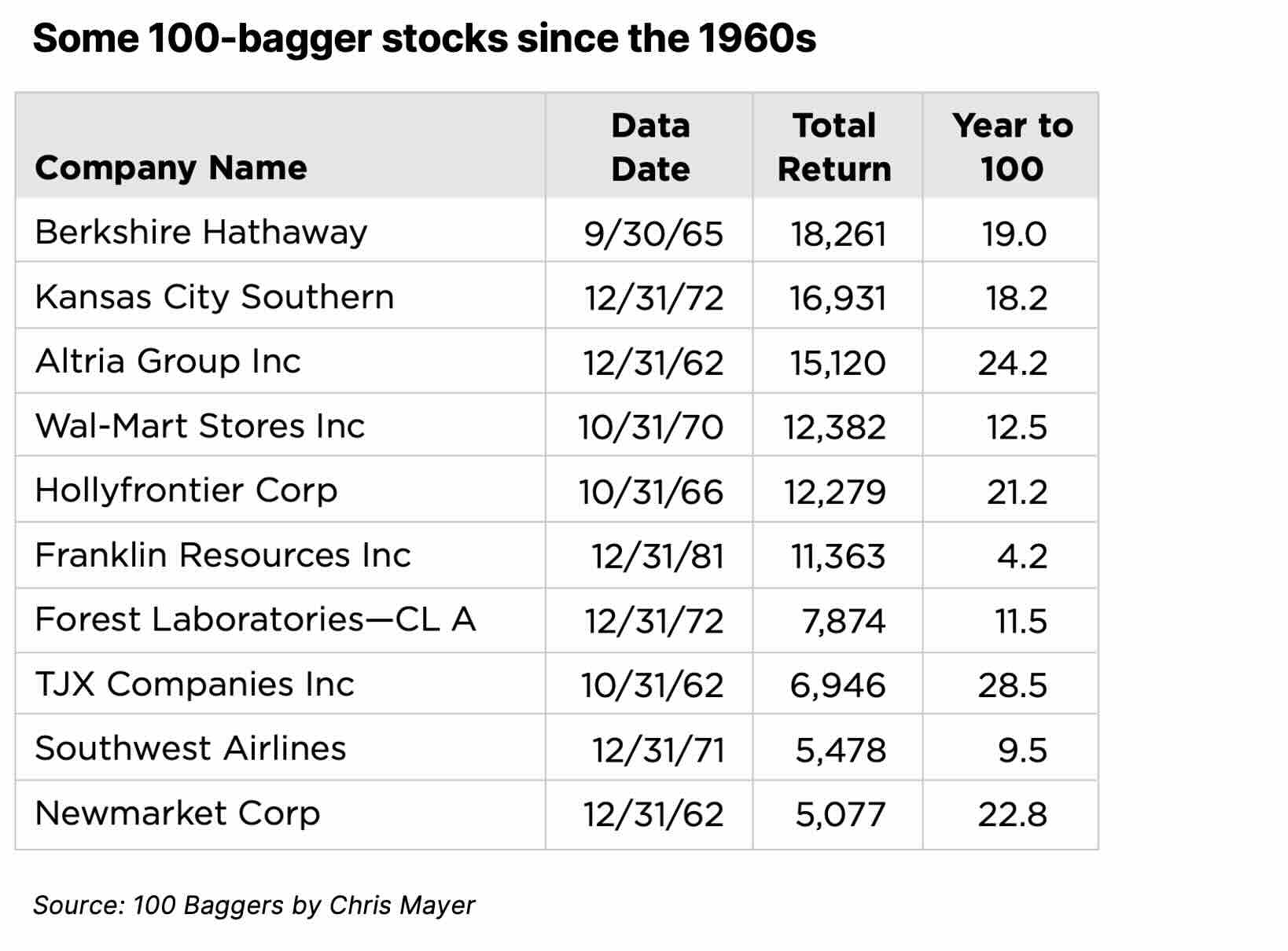

But they do not determine your long-term success. Many great stocks went through all kinds of periods, including wars, oil shocks, social unrest, and economic recession and still delivered outstanding results. There are many 100-baggers out there (stocks that returned 100x shareholder money over 20-40 years) that delivered those returns in different market conditions. However, these companies achieved this phenomenal result by providing outstanding service to customers, finding new growth opportunities, and eventually growing their economic profits over the long term.

Is there still an upside in AI-related stocks? Will Trump’s victory crash markets? Will there be a military conflict between China and Taiwan? Will the FED cut interests this year?

Don’t get more wrong. All these developments impact markets. If rates fall, stocks will get a boost.

But they do not determine your long-term success. Many great stocks went through all kinds of periods, including wars, oil shocks, social unrest, and economic recession and still delivered outstanding results. There are many 100-baggers out there (stocks that returned 100x shareholder money over 20-40 years) that delivered those returns in different market conditions. However, these companies achieved this phenomenal result by providing outstanding service to customers, finding new growth opportunities, and eventually growing their economic profits over the long term.

Lesson 2: Invest as if the stock market will be closed for the next 10 years

“Only buy something that you'd be perfectly happy to hold if the market shut down for 10 years. If you aren't willing to own a stock for 10 years, don't even think about owning it for 10 minutes."

- Warren Buffett

This concept is equally powerful and similar to the first idea. It forces you to ask the right questions. Knowing that there will be no buyers for your stock, you stop worrying about what potential buyers may think of your shares tomorrow or next year. You start focusing on the performance of the actual business. You also pay more attention to the people running the company in which you are invested.

In short, you start thinking like a business owner, not a financial gambler.

For me personally, understanding how a business generates returns is crucial. What does it charge customers, and why? What are the alternative options for clients? How much does it cost to deliver the product? How may the cost structure change in the future?

And the most important question: Will the product be in demand in 10 years? Will people need it?

These are all the questions that come to mind if you start with Question 2 (above).

In short, you start thinking like a business owner, not a financial gambler.

For me personally, understanding how a business generates returns is crucial. What does it charge customers, and why? What are the alternative options for clients? How much does it cost to deliver the product? How may the cost structure change in the future?

And the most important question: Will the product be in demand in 10 years? Will people need it?

These are all the questions that come to mind if you start with Question 2 (above).

Lesson 3: Circle of competence

“You only have to be able to evaluate companies within your circle of competence. The size of that circle is not very important; knowing its boundaries, however, is vital.”

“I don't try to jump over 7-foot bars; I look around for 1-foot bars that I can step over.”

- Warren Buffett

The third question comes naturally once you try to answer the first two discussed earlier. How much do you actually know about a particular sector and company? Many years of sell-side research made me think hard about the growth rate I should use in Year 10 or the operating margin assumption in Year 6. I know many analysts who also spent considerable time debating various WACC inputs.

But when you invest your own money, the first thing you want to do is avoid things you have no clue about. If I know just a few basic things about India, I should not be looking at an Indian mid-cap operating in a particular region of that country. Regardless of what I think about AI, I am just not qualified to judge NVIDIA products and their future sales (not to mention profits). At least not when the whole world is focused on this company.

Warren Buffett and his long-term business partner, Charlie Munger, were brilliant because they showed by example that it was okay not to know everything and admit your limitations. It is much more important to know what you really know (the boundaries of your knowledge) than to try to get an edge in a complex situation.

But when you invest your own money, the first thing you want to do is avoid things you have no clue about. If I know just a few basic things about India, I should not be looking at an Indian mid-cap operating in a particular region of that country. Regardless of what I think about AI, I am just not qualified to judge NVIDIA products and their future sales (not to mention profits). At least not when the whole world is focused on this company.

Warren Buffett and his long-term business partner, Charlie Munger, were brilliant because they showed by example that it was okay not to know everything and admit your limitations. It is much more important to know what you really know (the boundaries of your knowledge) than to try to get an edge in a complex situation.

Lesson 4: Wait for the fat pitch

"The trick in investing is just to sit there and watch pitch after pitch go by and wait for the one right in your sweet spot, and if people are yelling, 'Swing, you bum!' ignore them."

- Warren Buffett

This idea is equally related to the three concepts above. Having a particular area of expertise and taking a long-term approach would inevitably narrow your investable universe. Suddenly, you realise that the stocks discussed in the media and financial blogs are just not for you.

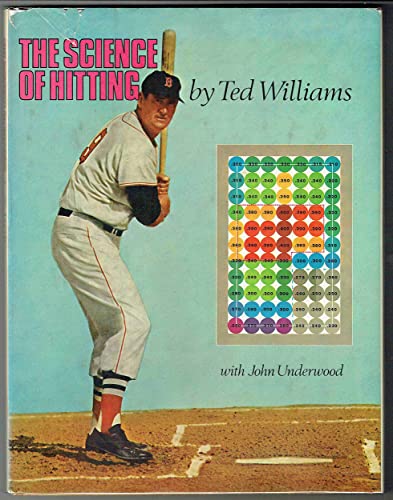

And here comes the genius of Warren Buffett, who brought the concept from baseball to investing.

And here comes the genius of Warren Buffett, who brought the concept from baseball to investing.

Do not rush to buy the first stock that catches your attention. Know the criteria of the business you want to own and just wait until you see it. Let opportunities pass; you get no extra points for just doing stuff.

The big change in my own investment approach happened when I realised that, unlike in most areas of life, in investing, doing nothing can often deliver better results than being too active. This is hard to grasp since we are taught from the early days that to achieve something, we have to work hard. We often associate good results with lots of activities on the way to achieving them.

Even in the world of professional finance, if you are an equity analyst who does not have a new idea at least every month, you will be under pressure from your managers and co-workers. A portfolio manager with the same stocks in a portfolio will receive many questions from clients and consultants on whether he is staying on top of the latest developments in the market. He will surely be questioned whether he is missing promising opportunities in the most innovative sectors of the economy.

I am grateful to Warren Buffett for giving us the permission to ‘do nothing’ (when you invest your own money, at least). Buying Berkshire 50 years ago and doing nothing else would probably put into 0.01% of all fund managers. An easy ride for a private investor, although not so easy for professional investors.

The big change in my own investment approach happened when I realised that, unlike in most areas of life, in investing, doing nothing can often deliver better results than being too active. This is hard to grasp since we are taught from the early days that to achieve something, we have to work hard. We often associate good results with lots of activities on the way to achieving them.

Even in the world of professional finance, if you are an equity analyst who does not have a new idea at least every month, you will be under pressure from your managers and co-workers. A portfolio manager with the same stocks in a portfolio will receive many questions from clients and consultants on whether he is staying on top of the latest developments in the market. He will surely be questioned whether he is missing promising opportunities in the most innovative sectors of the economy.

I am grateful to Warren Buffett for giving us the permission to ‘do nothing’ (when you invest your own money, at least). Buying Berkshire 50 years ago and doing nothing else would probably put into 0.01% of all fund managers. An easy ride for a private investor, although not so easy for professional investors.

Lesson 5: Risk of the business

“Risk with us relates to several possibilities. One is the risk of permanent capital loss. And then the other risk is just an inadequate return on the kind of capital we put in. It does not relate to volatility at all."

"Our See's Candy business will lose money in two-quarters of the year. So it has a huge volatility of earnings within the year. It's one of the least risky businesses I know...You can find all kinds of wonderful businesses that have great volatility and results. But it does not make them bad businesses. And you can find some terrible businesses that are very smooth. I mean, you could have a business that did nothing, you know? And its results would not vary from quarter to quarter, right? So it just doesn't make any sense to translate volatility into risk."

- Warren Buffett

This is a concept that is widely known, but often misunderstood. When young investors learn about this concept for the first time, they often start mistakenly disregard market movements. Holding a stock with a 30% loss, they can comfortably blame ‘irrational’ market, or investors who ‘are just too emotional’.

However, you can only ignore the price movements if you are sure about your edge and you know more about the business than an average market participant. You can even buy more of the stock that is losing you money.

But often, investors do not do enough research and skip straight to this point, ignoring big moves (especially declines) until it is too late.

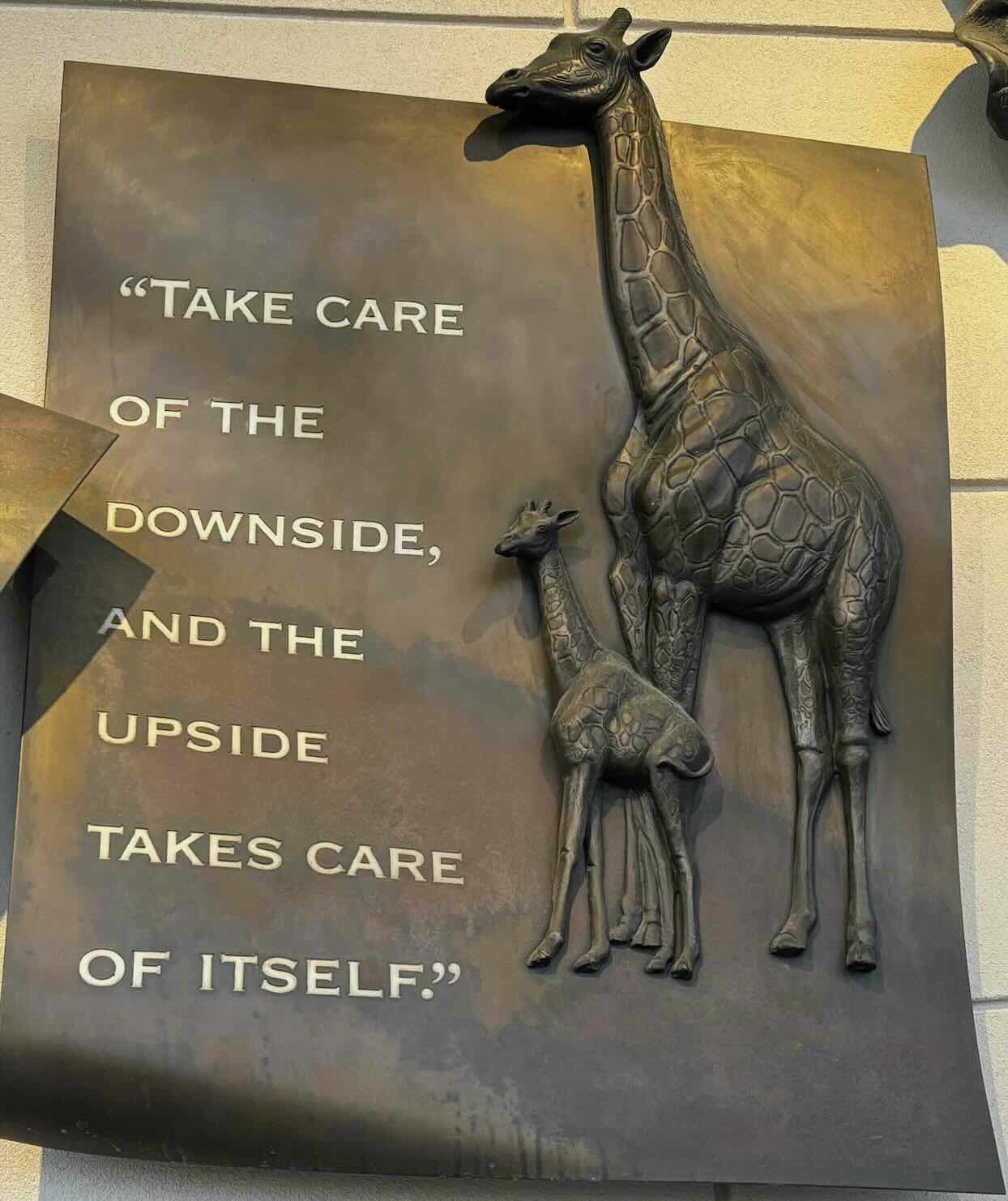

Studying Warren Buffett taught me the importance of focusing on downside risks and thinking about how you can lose money. Avoiding big losses is more important than chasing more upside.

However, you can only ignore the price movements if you are sure about your edge and you know more about the business than an average market participant. You can even buy more of the stock that is losing you money.

But often, investors do not do enough research and skip straight to this point, ignoring big moves (especially declines) until it is too late.

Studying Warren Buffett taught me the importance of focusing on downside risks and thinking about how you can lose money. Avoiding big losses is more important than chasing more upside.

“One investment rule at Berkshire has not and will not change: Never risk permanent loss of capital. Thanks to the American tailwind and the power of compound interest, the arena in which we operate has been – and will be – rewarding if you make a couple of good decisions during a lifetime and avoid serious mistakes.”

- Warren Buffett’s 2023 Shareholder Letter

"As for the future, Berkshire will always hold a boatload of cash and U.S. Treasury bills along with a wide array of businesses. We will also avoid behaviour that could result in any uncomfortable cash needs at inconvenient times, including financial panics and unprecedented insurance losses. Our CEO will always be the Chief Risk Officer – a task it is irresponsible to delegate. Additionally, our future CEOs will have a significant part of their net worth in Berkshire shares, bought with their own money. And yes, our shareholders will continue to save and prosper by retaining earnings."

- Warren Buffett’s 2022 Shareholder Letter

Lesson 6: Trust and Integrity

“It’s better to hang out with people better than you. Pick out associates whose behaviour is better than yours, and you’ll drift in that direction.”

- Warren Buffett

My other takeaway, which is a bit less obvious, is how much emphasis Buffett puts on human qualities.

Somebody once said that in looking for people to hire, you look for three qualities: integrity, intelligence, and energy. And if you don't have the first, the other two will kill you. You think about it, it's true. If you hire somebody without [integrity], you really want them to be dumb and lazy."

- Warren Buffett

He is never tired of praising people for their qualities, complementing his business associates and managers like Greg Abel and Ajit Jain.

But it is also instructive how ruthless he was with David Sokol, firing him immediately once he had a reason to doubt Sokol’s integrity. David Sokol was a former partner of Greg Abel, who together built the MidAmerican energy business before selling it to Berkshire in 1999. In January 2011, Sokol first purchased $10mn worth of stock in Lubrizol (a chemical company) before presenting Lubrizol to Buffett as a potential investment opportunity. Berkshire ended up buying Lubrizol at a premium which helped Sokol earn c. $3mn. He failed to mention to Buffett that he bought the shares of Lubrizol. While this was not a direct hit to Berkshire’s business, it was a strong enough reason for Buffett to part ways with David Sokol.

Many financial institutions would probably have found a reason to keep such a talented employee so that he could continue to generate more profits in the future.

Interestingly, David Sokol went on to start a container shipping business (Atlas Corp), which first received an investment from Prem Watsa’s Fairfax Holdings and was eventually acquired by a consortium including Fairfax, David Sokol and other investors.

But it is also instructive how ruthless he was with David Sokol, firing him immediately once he had a reason to doubt Sokol’s integrity. David Sokol was a former partner of Greg Abel, who together built the MidAmerican energy business before selling it to Berkshire in 1999. In January 2011, Sokol first purchased $10mn worth of stock in Lubrizol (a chemical company) before presenting Lubrizol to Buffett as a potential investment opportunity. Berkshire ended up buying Lubrizol at a premium which helped Sokol earn c. $3mn. He failed to mention to Buffett that he bought the shares of Lubrizol. While this was not a direct hit to Berkshire’s business, it was a strong enough reason for Buffett to part ways with David Sokol.

Many financial institutions would probably have found a reason to keep such a talented employee so that he could continue to generate more profits in the future.

Interestingly, David Sokol went on to start a container shipping business (Atlas Corp), which first received an investment from Prem Watsa’s Fairfax Holdings and was eventually acquired by a consortium including Fairfax, David Sokol and other investors.

Lesson 7: Being open about your mistakes

“I make plenty of mistakes and I'll make plenty more mistakes, too. That's part of the game. You've just got to make sure that the right things overcome the wrong ones.”

“Part of making good decisions in business is recognizing the poor decisions you've made and why they were poor. I've made lots of mistakes. I'm going to make more. It's the name of the game. You don't want to expect perfection in yourself. You want to strive to do your best. It's too demanding to expect perfection in yourself.”

- Warren Buffett

Buffett is never shy or embarrassed to admit his mistake. He is generally quick to fix it, which in most cases is just selling a stock. For example, in 2011, he bought IBM stock for $10.7bn, which made it in Berkshire’s Top 4 positions. IBM stock was range-bound during the time Berkshire was its shareholder, significantly underperforming new emerging tech giants. When Berkshire sold IBM in 2018, its stock was c. 10% lower than in 2011 (several hundred per cent underperformances relative to tech stars like Alphabet, Amazon or Meta).

Buffett sold airline stocks after they dropped 30-40% in March 2020, when many retail investors were buying them (those stocks bounced back 100% from the March lows in just 12-15 months).

But for Buffett, the bigger concern was avoiding unnecessary risk and putting the future of Berkshire and its shareholders into doubt.

His winnings far outweigh his mistakes. While some criticised him for being late to re-enter the market in 2020, he unexpectedly put $6.3bn into five Japanese conglomerates, which are now up c. 3x. He also borrowed at record-low interest rates in Japanese Yen, making it essentially a leveraged bet which further boosted equity returns for Berkshire.

Some investors question why he sold TSMC in less than six months after buying it last year. But Buffett is never afraid to look silly or inconsistent. If he does not think it is the right investment going forward or he discovers something during further research, he will be quick to sell a stock.

Few realise that, on average, he holds more than 60% of the stocks in his portfolio for less than 12 months. He is sure to hold on to his winners forever but equally sure to let other stocks go, disregarding what others may think of his investments.

I wrote this text on the flight to Omaha. But just as I was about to switch off my laptop, one more idea crossed my mind. For a second, I felt this rare moment of quiet happiness. It is not the happiness of standing on a pedestal with a trophy after a long, enduring competition. It is also not the happiness of a scientist who finally makes a discovery.

But it is that feeling of happiness when you appreciate how lucky you are to be alive, to enjoy life as it is, to travel, to meet old and new friends, and to just enjoy life.

This man I was going to listen to on Saturday (4 May), had revealed his formula for happiness many times before. He is doing what he loves doing the most, playing by his own rules and with the people he admires. And he is not doing it for money, having lived in the same house for 66 years in the quiet Midwestern city of Omaha and leaving 99% of his net worth to charity.

This is Buffett in his own words about happiness and money:

Buffett sold airline stocks after they dropped 30-40% in March 2020, when many retail investors were buying them (those stocks bounced back 100% from the March lows in just 12-15 months).

But for Buffett, the bigger concern was avoiding unnecessary risk and putting the future of Berkshire and its shareholders into doubt.

His winnings far outweigh his mistakes. While some criticised him for being late to re-enter the market in 2020, he unexpectedly put $6.3bn into five Japanese conglomerates, which are now up c. 3x. He also borrowed at record-low interest rates in Japanese Yen, making it essentially a leveraged bet which further boosted equity returns for Berkshire.

Some investors question why he sold TSMC in less than six months after buying it last year. But Buffett is never afraid to look silly or inconsistent. If he does not think it is the right investment going forward or he discovers something during further research, he will be quick to sell a stock.

Few realise that, on average, he holds more than 60% of the stocks in his portfolio for less than 12 months. He is sure to hold on to his winners forever but equally sure to let other stocks go, disregarding what others may think of his investments.

I wrote this text on the flight to Omaha. But just as I was about to switch off my laptop, one more idea crossed my mind. For a second, I felt this rare moment of quiet happiness. It is not the happiness of standing on a pedestal with a trophy after a long, enduring competition. It is also not the happiness of a scientist who finally makes a discovery.

But it is that feeling of happiness when you appreciate how lucky you are to be alive, to enjoy life as it is, to travel, to meet old and new friends, and to just enjoy life.

This man I was going to listen to on Saturday (4 May), had revealed his formula for happiness many times before. He is doing what he loves doing the most, playing by his own rules and with the people he admires. And he is not doing it for money, having lived in the same house for 66 years in the quiet Midwestern city of Omaha and leaving 99% of his net worth to charity.

This is Buffett in his own words about happiness and money:

“If you have $100,000 and you’re an unhappy person and you think ”$1 million is going to make you happy, it is not going to happen.”

“I wasn’t unhappy when I had $10,000 when I got out of school. I was having a lot of fun.”

When asked what he values most in life now, Buffett said, “It's the two things you can't buy: time and love.”

I am posting this article the following morning after attending the meeting on 4 May 2024. There is a lot to go through, and there are points that are worth highlighting and sharing, which I will do separately.

But here is the quote I want to finish this article with.

Warren Buffett, when asked whether he would do anything differently looking back at his life, gave the following answer:

But here is the quote I want to finish this article with.

Warren Buffett, when asked whether he would do anything differently looking back at his life, gave the following answer:

“I can figure out all kind of things that should have been done differently but so what. I am not perfect. I don’t believe in lots of self-criticism or being unrealistic about what you are or what you’ve accomplished… I don’t think there is any room in beating up yourself over what’s happened in the past… It’s happened. And you’ve got to live the rest of your life and you don’t know how long it will be. And you keep trying to do the things that are important to you.

I really enjoy managing money for people who trust me. I don’t have any reason to do it for financial reason…I am not trying to run a hedge fund. I just like the feeling of being trusted. Charlie felt the same way. That’s a good way to feel in life, and it continues to be a good feeling. If I am very lucky, I get to play it for another six or seven years. It could end tomorrow. But that’s true of everybody, although the equation is not exactly the same…

I believe in trying to find what you are good at [and] what you enjoy. And then one thing that you could aspire to be because this can be done by anybody and that’s amazing and that doesn’t have to do with money but you can be kind and the world is better off. I am not sure if the world is better off if I am richer…If you are being kind, then you are doing what most rich people don’t do, even when they give away money. And I would say that if you’re lucky in life, make sure a bunch of other people are lucky too.”

If this is the only takeaway from your trip to Omaha, it was a worthwhile trip!

Thank you for reading. I hope you enjoyed this post. Please share it with people who may find it useful.