25 September 2022

A slightly different format of today’s article

Whenever I think about publishing my thoughts, I ask myself how relevant this would be for my readers. I often face a dilemma between writing about things I am most certain about (‘this is the best investment opportunity in our lives’) and something I consider important but may lack a specific conclusion or action point.

By focusing too much on writing the first type of articles, I risk writing extremely infrequently and eventually falling out of my readers’ radars. Writing about mundane things is another risk if I only focus on the most certain things (One day I will die is one of the few forecasts I am 100% sure about).

Today’s post differs from most of my previous ones because I will not write about the stock I have just bought (i.e. feel pretty sure about talking about it publicly) or a skill that can improve your decision-making. I am going to write about Amazon. I used to own Amazon in the past and have been following the company after I sold out. Besides, I will share a few interesting data points from a recent article in The Economist, which I am sure will be of interest to anyone looking at the Tech sector.

In investing, similar to other intellectual competitions like chess or poker, your thought process is more important than a particular outcome. Suppose I win against Magnus Carlsen in chess because he was distracted and made a blunder (extremely unlikely, but theoretically possible). I will feel good about my victory, but it will not improve my bleak chances in a ten-game match against Magnus.

Today’s post is more about the thought process: I will show how applying my investment approach to stock selection coupled with the new information changes my views on specific stocks.

My Investment Approach (in 2 minutes)

I look at each stock as interest in the business. To understand whether a stock is worth buying, I first try to understand the business and then how much it could be worth. I start with the company’s product or service to understand the business. How critical is it for consumers, and what are alternative solutions? I look into the economics of the business. How much does the business charge for its product, and how much does it take to produce?

I also analyse how the business funds itself (debt, equity which could be new shares issue or reinvesting prior year profits, or even working capital). Related to this is what the company is doing with its excess cash that is left after all necessary expenditures (including Capex).

Before I decide how much the business could be worth, I need to understand at what rate it can grow in the future. In broad terms, this means how much demand for such a product could be and what market share the business can capture. In microeconomics, this means how much more units the firm can sell in the future and how much it can raise prices for its products (its pricing power).

These questions help me understand what the business could be worth. The classic formula for valuing a business is the following:

Value = FCF / (WACC - G)

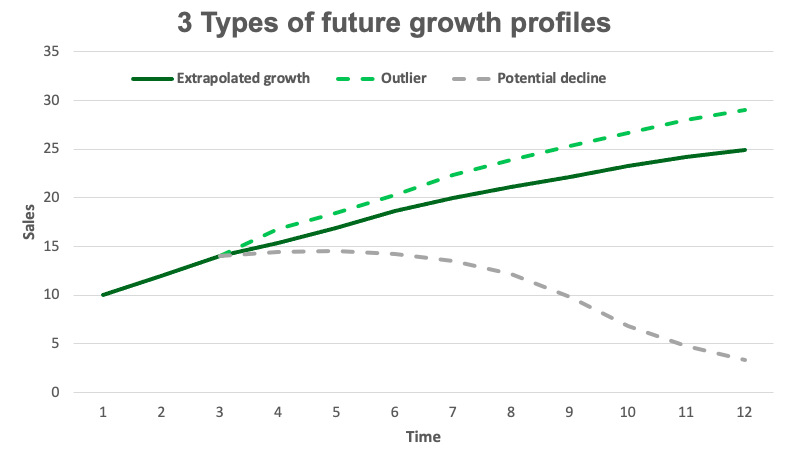

Investors’ most common mistake is focusing too much on the formula and financial statements needed to work out the key ratios. Eventually, they tend to extrapolate the latest financial results far into the future.

In reality, many companies do not operate for more than 20 years. On the other hand, rare outliers can grow at much higher rates for much longer.

Extrapolating works best for established businesses with durable competitive advantages (what Buffett calls ‘moats’). How likely is the company to maintain its edge over competitors, better pricing, more efficient cost structure, new innovative products, allocating capital and so on?

Here comes the importance of collecting critical data points and anecdotal evidence (e.g. ‘all SMEs I know prefer the cloud service of …Amazon (or Google, or Microsoft)’).

Before I move to the most interesting data points, a quick word on WACC. I use a rate of 10%. Rather than spend time analysing government bond yields, betas, equity risk premiums etc., I prefer to spend it on understanding the business better or searching for new companies. It also feels great that if you value your business at a 10% discount rate, you would not worry too much whether 10Y Treasures are at 4% and whether they would move back to 2% at some point (or 3%). Finally, 10% matches long-term equity returns for businesses and adequately reflects my conservative investment expectations (in case you wonder why not use 5% or 20% instead).

P.S.: You can find a more detailed list of questions I try to answer when analysing a company in my previous post.

The most interesting data points which I found this week (especially on Amazon)

- With $31bn in ad sales in 2021, Amazon is on track to generate 7% of all global digital ad revenue in 2022, which is over 7x higher compared to 6 years ago. Its ad business is roughly the same as the sales of the entire global newspaper industry.

- Microsoft sells more ads than TikTok. LinkedIn generates more revenue than Snapchat or Twitter. Its ads let it monetise the time users spend on it at roughly four times that of Facebook (eMarketer).

- Apple is already selling as many ads as Twitter. The company is rumoured to be preparing to introduce ads on its Maps app to promote local businesses. As it moves further into payments, it could better learn its customers’ shopping habits.

- The article argues that Meta looks most vulnerable as it relies more on interest-based ads. It has become harder to track users following rules on app-tracking transparency introduced by Apple last year and Digital Services Act unveiled by the EU this year, with a similar law expected in the US.

- Google is better positioned to take advantage of the coming changes with its healthy search ads and its vast YouTube video and audio services. Still, its ad business will face stronger competition from emerging rivals, which could impact its growth rate and margins.

- Amazon, Apple and Microsoft are in the best position among the Big Tech as they use more first-party data, which they collect directly on their own platforms.

- Video streaming is becoming an essential source of ad revenue growth for Amazon and Apple.

- Microsoft’s expansion in gaming is another avenue. Its recent acquisition of Xandr, an ad-tech company, has further strengthened its capabilities, especially in serving ads for other streamers. As a further testament to the growing strength of Microsoft, recall that Netflix has appointed Microsoft to provide the advertising technology for its ad-supported tier.

How is it relevant for Amazon?

Amazon is one of the greatest businesses in modern history. It has grown its revenue at a 28% annual rate from 2000 until 2021. If you invested $1,000 into Amazon at IPO, your money would grow to about $2.3mn by now (38% annualised growth rate).

However, Amazon’s revenue profile started to flatten recently, growing just 7% in Q2 2022. Its profit margins have also been under pressure declining from 5.2% in 2019 to 2.7% in Q2 2022. To what extent these changes are the high-base effect on the back of the COVID-driven online boom and how much of this slowdown is a symptom of maturing business and a new, more moderate growth in the future is the critical question.

The market has noticed that, the company’s share price has been flat since mid-2020 and down 39% from its peak last year.

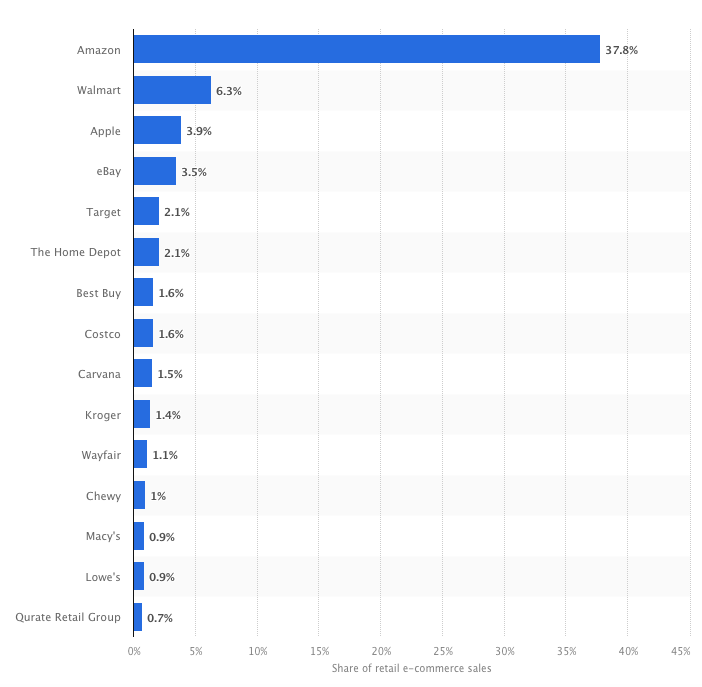

Clearly, Amazon’s core e-commerce business cannot keep growing at a previous 20+% rate, given its scale. With 38% of all e-commerce sales in the US going through Amazon (according to Statista), gaining further market share looks challenging. The overall online format (currently at 15%) may increase its share in total retail sales to probably 30%, maybe even higher. This, together with the overall inflation and long-term economic growth, should allow Amazon to achieve 10% growth comfortably, perhaps a little more (in the next ten years at least).

Key e-commerce players in the US

The other essential element of the company’s investment case has been its unique track record in reinvesting profits (first in customer loyalty through reduced margins and subsidised delivery) and second into new businesses. Amazon has tried dozens of various new products, including its own smartphone (Fire), Amazon Local Register (a competitor to Square), Askville (analogue of today’s Quora) and many others. Most of them eventually failed.

But few have survived and become outstanding businesses. The jewel in the crown is Amazon Web Services - the largest cloud business in the world (on track to deliver almost $80bn in revenue in 2022 at a 32% operating margin), well ahead of Microsoft Azure or Google Cloud.

Amazon is the third largest player in the advertising sector globally, behind Google and Meta. Amazon has been growing its ad sales at over 50% over the past eight years (35% in 6M22), more than twice as fast as Google or Meta. With $31bn in revenue in 2021, it is close to the global ad sales of the entire newspaper industry.

The Economist article, which I referred to above, underscores the value creation at Amazon and provides more inputs for the company’s valuation.

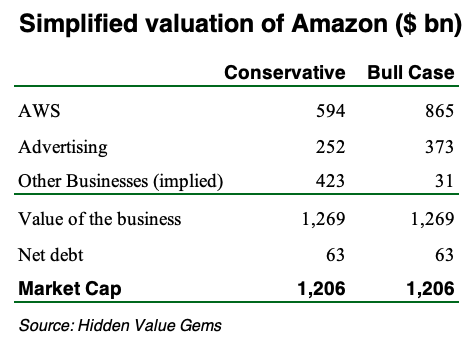

My simplified view of what Amazon could be worth is using two sets of assumptions (conservative and more optimistic).

Conservative assumptions:

- AWS continues to grow at only 33% in the next three years (compared to 37% and 33% in Q1 and Q2 this year, 38% CAGR for the 2016-21 period). I assumed a moderate improvement in operating margin to 35% by 2025 (margin was 25% in 2016, 30% in 2021 and 32% in 1H22).

- I applied a 12x EV/EBIT multiple to operating profit in 2025 and discounted it to today using a 10% rate. 12x multiple corresponds to an 8.3% yield (pre-tax) which is reasonably conservative given that the business could continue growing at well over 10% beyond 2025.

- I assumed 33% annual growth for the ad business (during 2022-2025), which is significantly lower than the 57% rate achieved in 2020 and 2021. It is above 25% and 21% growth rate delivered in Q1 and Q2 this year (which was marked as a general slowdown in online advertising, especially on the back of the high base effect of 2021).

- I assumed a 33% operating margin for the advertising business in 2025, below Meta and Google.

- I also applied a 12x EV/EBIT multiple to 2025 profits and discounted the value to today using a 10% rate.

- Such assumptions for the value of AWS ($594bn) and Advertising ($252bn) imply that Other businesses are worth $423bn, given that Amazon’s total Enterprise Value is $1,269bn.

It does not strike me as extremely low, but on the other hand, for $423bn, you ‘get’ the largest e-commerce business, Prime Video streaming with over 200mn members, and one of the largest logistics businesses in the world. And finally, given Amazon’s track record in creating new businesses, one can argue that Amazon can launch more than one similarly successful businesses that will be worth billions in the future.

Even more interesting is that under more optimistic assumptions, the value of Other businesses drops to just $31bn (essentially, you only pay for the two businesses at the current price).

Bull Case

In the Bull Case, my growth rate assumptions for AWS and Advertising were 37% and 35%, respectively, while the operating margin (2025) is 40% for both. I also applied a 14x EV/EBIT multiple since faster-growing and more profitable businesses would demand a higher valuation.

Conclusion on Amazon

Going back to the Conservative Case, the question now is whether $423bn is a reasonable price for every other business of Amazon. For reference, Walmart - the most prominent traditional retailer in the US with comparable sales to Amazon’s GMV, has a market cap of $353bn, FedEx - a leading independent delivery business - has a market cap of $39bn. Netflix, a leading video streaming company, is currently valued by the market at $101bn.

So, my conclusion is that under conservative assumptions, Amazon does not look incredibly cheap. Of course, it is an extraordinary business, with an extreme focus on a customer and a genuinely long-term focus. Its profitability can probably be higher if it were to slow down and focus on near-term cashflows rather than long-term growth.

It also has a powerful moat. Replicating the same scale of delivery hubs, warehouses and winning consumers’ minds will take years and cost dozens of billions of dollars. In the end, success is still not guaranteed.

If you pay roughly a fair price for the business, your return from such an investment will be driven by the growth of that business. The other source of return - re-rating of a valuation multiple - will not contribute if it remains at the same level.

It is reasonable to expect a 10-15% annual return from Amazon without betting on an optimistic scenario. Further upside comes from the more successful expansion of the core businesses and the launch of new business lines.

I have decided to pass on Amazon at this point. Given the severity of the market decline, more exciting opportunities should be available. Amazon is a well-covered company, and the market knows the business quite well. It is also a fairly big business, and the law of big numbers works against it.

The only scenario when Amazon could be worth buying is if you run a fairly passive portfolio and if you are looking for an inflation hedge. It is probably a better alternative to large consumer franchise names such as Unilever, P&G or Nestle. I believe it has a more substantial moat and a better culture.

Last word on Meta

The facts brought up by the article in The Economist also speak strongly against Meta. Or at least they confirm the vast challenges faced by the company. Its core advertising business is under pressure from the competition of new players like TikTok as well as Amazon and Microsoft. Regulatory changes and Apple’s privacy policy make it harder to collect user data, making its networks less interesting for advertisers.

I would definitely not consider Meta as a long-term investment. I think it is one of those cases where prices matter less as long as the core business is struggling. History knows many value traps - stocks which looked cheap but ended up as poor investments, for example, IBM or many US department stores (like Macy’s). To be clear, such stocks can stage a strong share price rally on the back of a short-squeeze or some positive quarterly results, but the long-term trend undeniably points lower.

I have recently considered Meta a few times as its valuation looked highly appealing. Still, I have never gotten comfortable with its moat’s strength, especially seeing TikTok emerging out of the blue and easily winning younger generations. The success of YouTube has also proven that there are many ways to attract new users and win a bigger share of the time they spend online.

I have shared my thoughts on Meta in another post published in March 2022.

Did you find this article useful? If you want to read my next article right when it comes out, please subscribe to my email list.