Investment approach with the best track record

When I just started thinking about my first investments, I struggled with choosing the ‘right’ investment approach. It took me quite a while to understand what was going on (dozens of books and articles, hundreds of hours of videos and years of practice ). I am a slow learner. I hope that what I wrote below will help investors who are at the start of their journey.

There are two ways to describe Value Investing, and this is what causes the confusion.

Strictly defined, Value Investing is buying stocks at prices below their intrinsic value. As a famous investor and author, Joel Greenblatt likes to say, ‘Figure out what the business is worth and pay a lot less for it’. There is little argument here. There are other methods (not based on business fundamentals), such as technical analysis, momentum, quantitative strategies and others.

But if you are in doubt about which method is better, just think about the wealthiest investors. How many of them used technical analysis to build wealth?

These two questions make it obvious (at least to me) that value investing (as defined above) is the superior method. Only some truly successful investors make decisions based on macro or non-fundamental factors, like Stanley Druckenmiller, George Soros, Ray Dalio.

Even the wealthiest business people, such as Jeff Bezos or Bill Gates, got to the top by deciding where to invest their time and capital based on fundamentals (future demand, competition, costs etc.). They have not become wealthy by trading assets.

Warren Buffett wrote an excellent article in 1984, called ‘The Superinvestors of Graham-and-Dodsville’ (the link to the article is in My Library). If you are still debating what investment approach to use, I recommend reading this article by Buffett.

What is the real challenge?

So why, then do you read articles on Whether Value Investing is Dead? Or What is Wrong with Value Investment Approach? - you can easily ignore them. Nothing can be wrong with paying less for something that is worth more.

But here comes the tricky part: How to establish the fair value of a business?

Theoretically, a business is worth all the cash flows it will generate in the future, discounted to today. The idea of discounting is to reflect the time value of money and alternative options. The alternative to investing in a business is putting money in a bank which would generate 3-5% interest income in the good old days. You could use a higher discount rate for your investment into a business to reflect additional risks (e.g. 10%). So you become indifferent between having $100 in one year after investing in a business or having $90.9 cash today. Invested at a 10% return, this $90.9 cash would turn into $100 in one year. In other words, the cash flow that your investment would generate in one year is only worth $90.9 today. The farther the cash flow is in the future, the less valuable it becomes in present terms.

There is nothing to disagree with for now, as it is all quite theoretical.

But how do you know what cash flow the business will earn in Year 2 or Year 10 and whether it will even remain in operation in the future? To complicate matters, what if the government raises taxes in the future, which would reduce the company’s income? Or, what if some of the company’s products are sold abroad in foreign currency? How do you know that the exchange rate would remain the same, and if it changes, by how much then?

This is where the disagreement begins. A narrow, more traditional Value Investing approach would emphasise the current or historical performance and avoid making long-term projections. An investor using such an approach would also look into current assets and liabilities. The logic is that if a company has historically earned $100 in annual profits (over the past ten years, for example) and has invested back (spent on CAPEX) the same amount as its depreciation charge in the P&L statement, generating the same $100 of free cash flow (FCF), then it is likely that this company would earn similar profits in the future, perhaps slightly higher if adjusted for inflation.

So a traditional value investor would not want to pay more than $1,000 for such a business (if he uses a 10% discount rate). He will also get additional comfort if the company’s book value of assets is $1,000 (as reported in the latest balance sheet). If there is no debt (construction of assets was financed with shareholders’ capital), then the company’s equity would be the same - $1,000.

He may even get more interested in the opportunity if the business earned just $50 in profits in the latest year, having made $100 annually for ten years prior to that, as long as he is confident in this business. One idea that is often used by traditional value investors is Mean Reversal. Returns on capital, profit margins and other key ratios may deviate in the short term but tend to go back to their historical averages in the long term. If it costs $1,000 to build a new plant, but current industry conditions reduce profits to only $50 a year, no new plant would be built (as you would get only a 5% return on your investment). Reduction in supply would rebalance the market and bring profits back to the historical ($100) level.

Businesses that experience deterioration in their financial performance tend to be valued at a discount. The market would apply a higher discount rate (lower earnings multiple) to reflect additional uncertainty and a possible further decline in profitability (if recent trends are extrapolated).

So a business whose earnings dropped 50% may be valued at 7-8x, instead of 10x, or as low as $350 (7x PE multiple X $50 earnings; or $50 earnings capitalised at 14.2%).

For a value investor, this could offer a double opportunity - recovery in earnings and normalisation of earnings multiple (reduction in discount rate) as long as the business is not in permanent decline.

A usual shortcut is to rank companies by main valuation metrics such as PE, Dividend yield, and P/B and pick companies with the lowest multiples. For almost a century, companies that were ranked lower outperformed companies with higher multiples. Not every year, but over the medium to long term.

However, since the Great financial crisis of 2008, low PE stocks have underperformed more expensive stocks. Overall returns of low PE stocks were about 10% p.a. which is in line with historical market performance, but the US market (measured by the performance of S&P500) has delivered substantially better returns (c. 15.5%, including dividends from 1 Jan 2009).

Reasons behind recent underperformance of Value Investing (narrowly defined)

There are at least 5 reasons why such a method has underperformed the broader market. The good news is that four reasons are temporary.

1. Interest rates - as rates dropped almost to zero (when I am writing this, 10-Year US Treasury yields are at 1.63%, German 10-year government bonds at negative -0.13%), the value of cash flow that would be earned far in the future became more valuable in today’s terms, while the value of near-term cashflow did not change as much. As a result, companies with the potential to earn considerably more in 5-10 years became more valuable compared to more stable businesses. This is a temporary issue, and with more signs of rising inflation, we could even be at an inflation point today (in late May 2021).

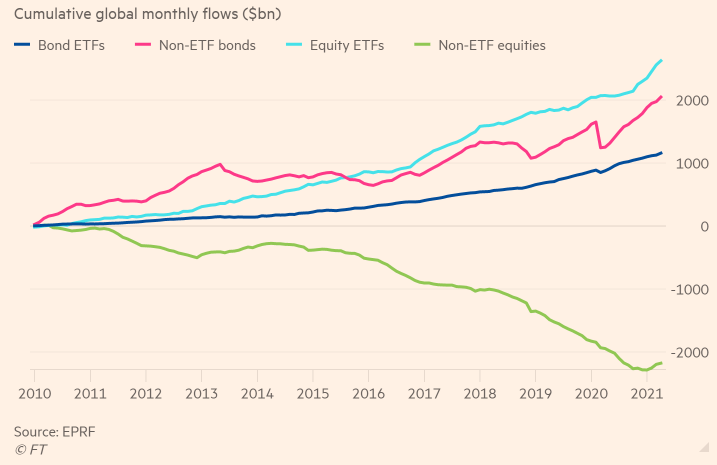

2. The rise of passive investing - a technological revolution led to the creation of low-cost funds (ETFs) that track the broader market as well as specific industries and regions, allowing retail investors to participate in the stock market more actively. As a result, ETFs have seen huge inflow at the expense of actively managed funds (where portfolio managers choose stocks based on fundamental indicators). ETFs make decisions on buying and selling not based on the valuation of companies, but based on the flow of money in and out of such funds, while individual stock selection is based on SIZE. So companies with rising market capitalisation attract more demand from passive funds, which leads to additional growth. This is also a temporary factor, as the market cannot be fully owned by passive funds. In fact, from late 2020, actively managed funds have started to see positive inflows (see chart below).

Until recently, actively managed funds have suffered outflows

Source: EPRF, Financial Times

3. Disruption - as new technologies are more actively used in various industries, this shortens the product life cycle, allows consumers to switch to new offers and makes traditional competitive advantages (moats) less relevant. If previously Gillette razors (now produced by Product & Gamble) were the only ones that could afford to spend billions on TV advertising and that scale was their key competitive advantage, now new start-ups like Dollar Shave Club or Harry’s can find their customers with more niche and low-cost advertising on the Internet. As a result, past earnings become much less useful in understanding the future earnings potential of the business. Many low-priced companies turned out to have serious issues with their business models and were permanently impaired (e.g. US brick-and-mortar retailers). The ability to envision the future has become more important. Soft factors, including management skills and the innovative culture of a company, often become more relevant than physical assets. Investments in innovation are just salaries paid to engineers as well as marketing expenses to promote new products and bring new customers. Such expenses are recorded in the P&L, boosting costs and reducing profits, unlike purchases of equipment which are recorded in the cash flow statement as well as in the balance sheet through additions to assets and equity (via earnings). As a result, a company which heavily invests in new technology can be loss-making with a very light asset base - a combination that will hardly make it appealing to traditional value investors. Yet, the real value that such a company can generate in the long term can be significant.

4. Faster earnings growth of tech giants - new technologies opened new markets and forced companies from old sectors to adapt to a new digital world by purchasing new services (e.g. cloud) - exactly as market participants expected in the late 1990s bidding up stocks of young tech companies to the sky. However, just a handful of companies managed to capture most of the benefits (often grouped under the FAANG acronym). These companies continued to generate earnings growth of well over 20% for more than a decade. Formally, stock return is the sum of (i) a Change in PE, (ii) dividend yield and (iii) and Change in Earnings. If a company does not pay any dividends and trades at the same multiple, then its stock return would match the earnings dynamic. In the case of FAANG stocks, investors could have achieved a 20% appreciation in the value of their stocks simply through this earnings growth. Traditional companies - a focus for value investors, not less because of past earnings and visible, tangible assets - had to spend more on new technologies and faced competition from new players, which negatively impacted their sales. In the end, the margins of many traditional companies were squeezed on top of declining sales - hardly a winning formula, even for low-priced companies.

5. Computers made financials transparent - low-priced stocks have become quickly discoverable. In Snowball, a biography book on Warren Buffett, the author described how the legendary investor would travel to a different town to get hold of an annual report of a particular company. Fifty years ago, your advantage could have been in seeing financials before everyone else. There was nothing illegal in this, rather just a lack of technology and focus. These days, not only can you get the latest financials in 2-3 clicks, but you can slice and dice all financial information as you wish. In fact, you don’t need to do it yourself; an algorithm would do it faster and with fewer mistakes. As a result, if private investor screens for low PE stocks now, most names he finds would be companies in real trouble (‘value traps’) facing huge debt problems, products becoming quickly obsolete or other challenges.

This last factor is definitely permanent, making the traditional analysis method less useful. However, the first four are likely temporary. Disruption and Faster earnings growth of tech giants (Reasons 4 and 5) cannot last forever. In fact, there were many other periods in history when technology changed our lives, like automobiles at the beginning of the past century (as Buffett mentioned this year at Berkshire’s shareholder meeting) or the invention of the radio, TV, aeroplanes, personal computers and so on. Earnings cannot continue to grow at 20% forever if the world’s economy is only growing at 3% (maybe 5% with inflation).

Value Investing is not about finding low-PE stocks

My main point is that Value Investing is not just picking stocks with low multiples. As I discussed at the beginning, Value Investing is paying less for what the business is worth.

A normal multiple of 15x PE (average for S&P 500 for over 100 years) may underestimate the value of a company that can double its earnings in three years and then double again in the following three years (26% CAGR). Just focusing on the price you pay when computers have screened thousands of companies already may not be enough to identify value.

Other investors (including Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger) look for the value that the company can generate over time. This depends not just on past investments but on investments yet to be made. Capital allocation, management team, ability to innovate and other factors (not easily quantifiable) are as important as the price you pay.

In fact, two quotes are important—one from Buffett and the other one from Munger.

- ‘It's far better to buy a wonderful company at a fair price than a fair company at a wonderful price’.

- ‘Over the long term, it’s hard for a stock to earn a much better return than the business which underlies it earns. If the business earns six per cent on capital over forty years and you hold it for that forty years, you’re not going to make much different than a six per cent return – even if you originally buy it at a huge discount. Conversely, if a business earns eighteen per cent on capital over twenty or thirty years, even if you pay a high-looking price, you’ll end up with one hell of a result.'

Advantages of Value Investing defined more broadly

So in the first, more narrow definition of Value Investing, you attempt to capture the discount (spread) between today’s market price and the company’s fair value (based on current assets, less liabilities underpinned by near-term earnings and dividends). In the second, broader definition, you try to take into account how much value can yet be created.

Besides evaporating opportunities as the Internet and computers uncover the remaining corners of the financial world, there are other disadvantages to the first method. If you buy a stock at a price that is two-thirds of its intrinsic value, you can achieve a 50% return once the price reaches a fair value. But it takes 3 years; then your annualised return drops to 14.5%. The fair value could also decline in the meantime (if you bought a brick-and-mortar retailer for 10x PE hoping it will be valued at 15x, but the retailer’s earnings continue to decline by 10% while you are waiting for the re-rating). You also need to pay tax each time you realise a gain, you pay your broker twice (when buying and then selling the same stock), and you also need to find a new idea to put your money.

Instead, if you owned just one company which reinvested its earnings at 20% return over 10 years, you would have paid less tax and less commissions. You would also not lose time looking for new opportunities after your statistically cheap stock gets revalued and you have to sell as it no longer is cheap.

What it takes to succeed

To succeed in investing, especially in the second method of estimating intrinsic value, you have to be a good business analyst, not just a financial analyst. The first method requires you to be a contrarian thinker. Low PE stocks are generally experiencing some problems, and there is a lot of news and opinions on the never-ending problems of a particular business. Both methods require patience. You need to let great companies compound and not sell them too early. You also need to wait for the turnaround to happen and for the market to appreciate the progress.

Understanding a company’s competitive position and whether it has any edge is very important in both methods. Competitive advantages (or ‘Moat’ as Warren Buffett calls it) determine how long a company can enjoy superior growth. In the first approach, it is also important to avoid value traps and for the company to deliver a turnaround and understanding business drivers helps a lot.

Summary

In the end, there could be nuances between various methods, but in essence, all Value Investors follow the same principles:

- They view stock as a share of the business. ‘Behind every stock, there is a business’, as Peter Lynch used to say.

- The value of a stock is based on all future cash flows that a company will generate discounted to the present.

- They are humble and realise that there are many unknowns, so having a view on every stock is impossible. They try to have an edge in analysis. They are quick to accept mistakes.

- They look to take advantage of market moves and changes in sentiment rather than follow it. Graham famously wrote in his Intelligent Investor book that ‘In the short run, the market is a voting machine, but in the long run, it is a weighing machine’.

- They have the patience to wait for the right opportunity, for the turnaround plan to start delivering results and for a great business to compound capital.

- They protect downside risks by focusing on the margin of safety, making sure they don’t overpay even for wonderful companies.

I hope that the above was useful. The last message I would like to leave you with is this: Value Investing may not be easy, but it is the surest thing to achieve the best investment results in the long term.

Did you find this article useful? If you want to read my next article right when it comes out, please subscribe to my email list.