It is becoming harder to ignore signs of a market correction. In this piece, I will first discuss the signs and then explain my plan for dealing with them.

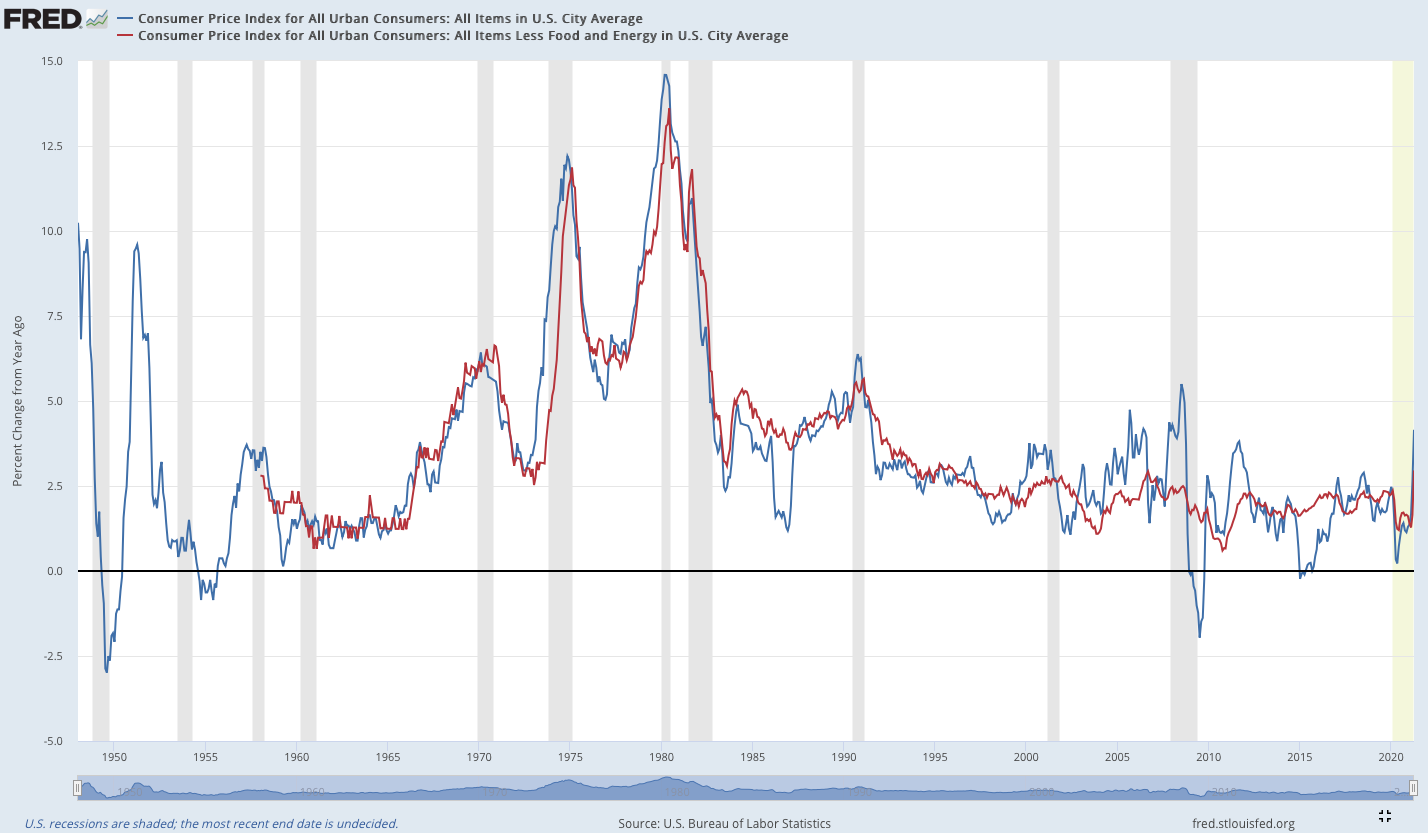

1. Inflation is picking up.

The factors behind inflation seem to be quite diverse, which makes it harder to stop it. There are both - supply-side as well as demand-side factors. For example, labour shortages in certain segments are pushing companies to raise salaries to find new employees. This is partially due to COVID-related financial aid that disincentivises workers from going back to work (or just health concerns). There are bottlenecks in the production of chips as well as certain commodities. Push for decarbonisation is displacing cheaper and dirtier energy sources raising overall electricity costs.

In the end, Central banks (including FED) will have to start raising interest rates which would change the discount rate for evaluating stocks and reduce their estimated values.

One of the best investors globally, Stanley Druckenmiller, believes that FED could raise rates quite quickly, which would trigger a meaningful market correction.

US Inflation after World War II

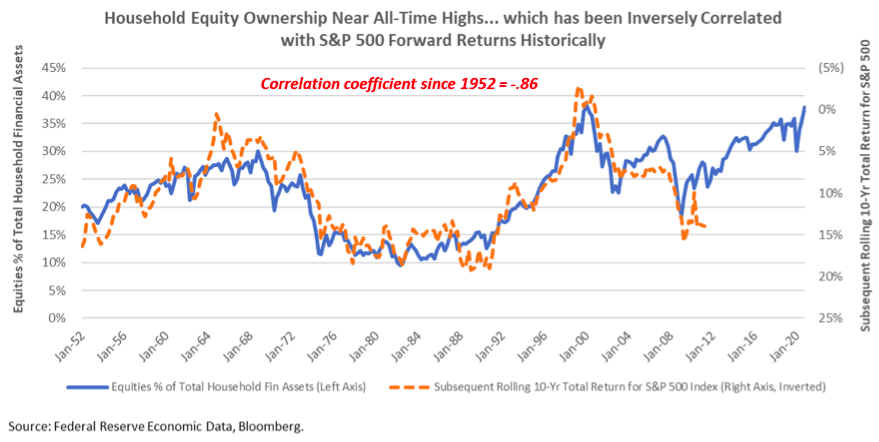

2. Retail participation has risen.

Rising stock prices have finally piqued the interest of retail investors who have generally remained cautious since the 2008 financial crisis. There are famous stories of how small investors squeezed ‘smart’ money in names like GameStop.

Equities now account for the highest share of US household assets (similar to the late 1990s)

I borrowed the chart above from Smead Capital Blog.

3. Valuation of at least the US market is high.

Not all markets are expensive, but at least the US market is when measured by traditional PE metrics. Even if we adjust for the fact that the market is dominated by Tech companies that deserve a higher PE multiple and earnings may be depressed due to COVID, it is hard to ignore that valuation levels for the US market are not attractive. Other markets rarely do well when US markets go into correction.

S&P 500 PE multiple over time

4. Euphoric behaviour.

Dramatic rise of SPACs, crypto-currencies and other market behaviour point to the fact that more market participants do not take into account fundamentals and often act irrationally, mostly anticipating higher prices tomorrow. SPACs are hard to analyse simply due to their nature. You only know the amount of capital such an entity would hold, but whether management would use this capital wisely and create value or overpay for an asset is very hard to know in advance. Yet, prices were rising by dozens of percent within the first days after SPACs went public.

5. Tension in US / China relations is rising.

Not much to say here as it is quite self-evident.

On top of that, some of the world’s best investors are warning of a likely market correction coming (e.g. Druckenmiller, Grantham, Mason Hawkins).

So what is the best course of action now?

I think it is quite simple. If you are retired, and you heavily rely on your investment income, then it makes sense to reduce your allocation to equities. Most likely, such people would not have high exposure to equities anyway.

For most other type of investors, I don’t think there is anything to do provided that they own high-quality companies which are not trading at crazy valuations.

I provide a list of reasons why I think the best course of action is to do nothing even if you are convinced that correction is coming:

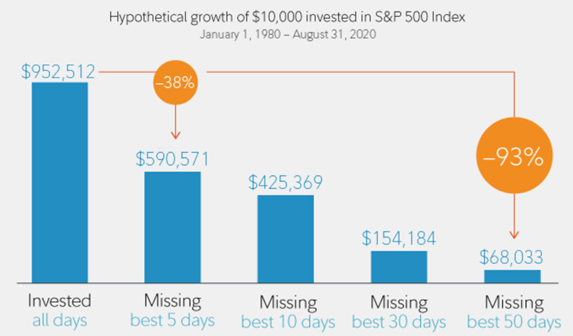

1. It is impossible to predict what markets will do next. Even Druckenmiller himself admits that he changes his view very often, so the fact that in May 2021, he was expecting correction does not mean he still expects it in June or September. The best example is to ask yourself what would you do if somebody told you about the upcoming pandemic in early 2020 (and consequent deaths, lockdowns, disruptions in the global economy). You would probably sell most of your holdings. If you just did nothing instead, you would have earned about 18% (at least this is how much S&P 500 gained in 2020, including dividends). Another related problem is that you can miss the turnaround since timing markets is impossible. If you sold stocks in early 2020, how would you know when to buy again? If you missed just 10 best days (when the market delivered the best returns) during the 1980-2020 period, your total return would have been just half compared to a fully-invested portfolio during all the time (I borrowed this chart from Fidelity):

2. Corrections occur regularly, but in the long-term, markets continue to move higher. During 1980-2018, there were 37 market corrections during which S&P 500 declined on average by 15.6%, according to Investopedia. Yet, during the same period, the stock market appreciated by 64.8x (or 11.3% per year). So if you put $1,000 into the index at the beginning of 1980, you would be sitting on a $64,814 portfolio at the end of 2018. To be clear, I think chances for the S&P 500 to generate the same level of returns in the next 20-30 years are much lower because we now deal with record-low yields, higher valuations and some issues with globalisations/protectionism. But, there are still opportunities at the level of individual companies.

3. Stock prices follow earnings in the long term. Great businesses are able to generate superior earnings. If you owned Wall-Mart or McDonalds, or other businesses from the early days, it would have been foolish to sell them in anticipation of market correction and risk of not buying again if you miss the bottom. Crises generally help great businesses to strengthen their market positions which in the long-term helps to generate higher returns on capital. Think about Berkshire and Warren Buffett, who currently struggles to deploy his $145bn cash position as most things are expensive, and he is competing against aggressive buyers with access to cheap funds (and these buyers earn based on deployed capital, so they are incentivised to spend faster as they are not paid on pure capital commitments/cash). Buffett could also accelerate buyback should Berkshire stock fall more, which would create more value than buying back stock at current prices. I sometimes think of stocks like boats in a sea race. A well-built boat with the great captain in charge will be the fastest to reach its destination, while weather conditions can occasionally slow it down but occasionally help her to sail faster. The key is to choose the most robust boat that would not crash during the storm and the most experienced, trustworthy crew that would do their best to avoid the wreckage.

3. Key risk is permanent loss of capital, not market volatility. If you own a business that goes bust, is involved in major fraud, has a product that becomes obsolete (e.g. Kodak) or simply trades at a ridiculously high valuation multiple (100x EV/Sales), then your risks of permanent loss of capital are very high. In most other cases, you should not worry too much about possible market corrections.

4. Inflation is a big risk for cash. Another problem with selling stocks due to expected market correction is that the value of your cash position may be eroded by inflation; in other words, you cannot preserve your purchasing power. If we indeed face higher inflation, then owning strong consumer brands that can relatively easy pass inflation to consumers and do not need to invest more into their business (don’t run large fixed assets). I also recommend to re-read Buffett’s 1977 article, which I have in My Library.

So, what I plan to do now is to review my holdings to make sure that leverage does not create problems and that businesses are generally doing fine. It is essential to get rid of stocks that you hold only because you hope to sell them at a higher price to someone else in the future. This can apply to ‘value’ stocks narrowly defined - a company that is trading at a low P/E with business in decline and run by weak management. In a rising market, you could have benefited from expanding multiples or stronger macro that could have supported the performance of ailing businesses. But in a period of economic stress, this becomes just a pure hope.

Otherwise, I plan to focus on finding great companies that are attractively priced, learning more about various sectors and managers — just as I have been doing before—and spending little time trying to guess about the market's next move. I think the returns on my time spent researching businesses and sectors would be much higher compared to time spent worrying and guessing.

Did you find this article useful? If you want to read my next article right when it comes out, please subscribe to my email list.