20 October 2024

Investors like themes. They sound exciting and add logic to otherwise random market moves. I am generally much more cautious when it comes to thematic investing. Since shares are pieces of real businesses, in the long term, their prices will reflect the performance of those businesses. Many great companies operated in slow-growing sectors (e.g. US auto parts), while the world’s fastest economies had many poorly performing companies (remember BRICS).

Besides, thematic investing shifts your attention from what matters (business performance and returns on capital) to just ‘stories’.

With this disclaimer out, I would nevertheless take the risk of sharing a theme I expect to have long-term consequences for investors.

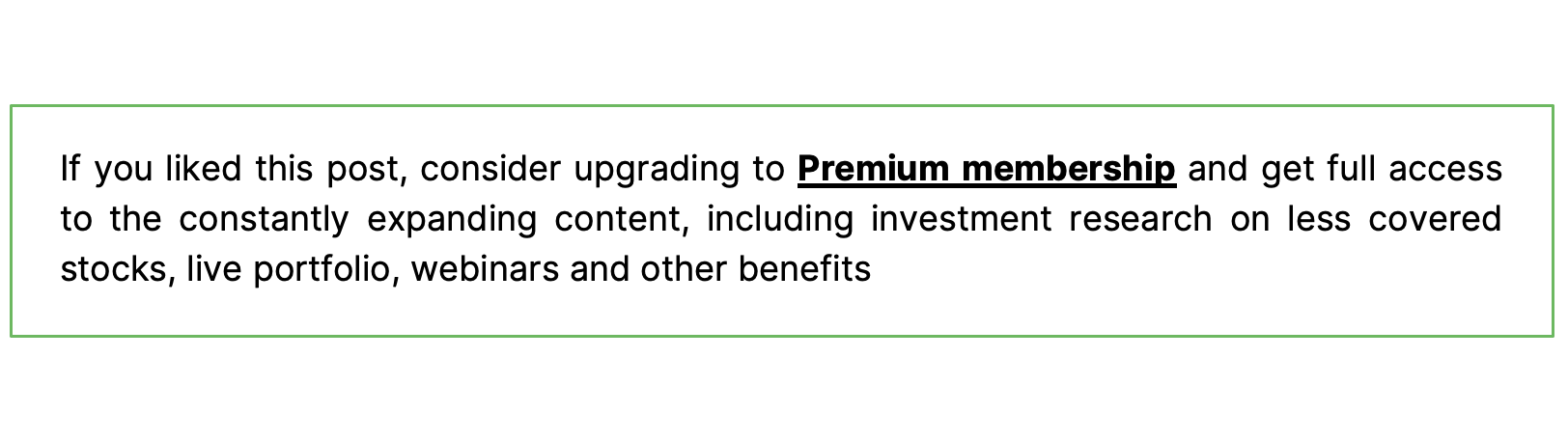

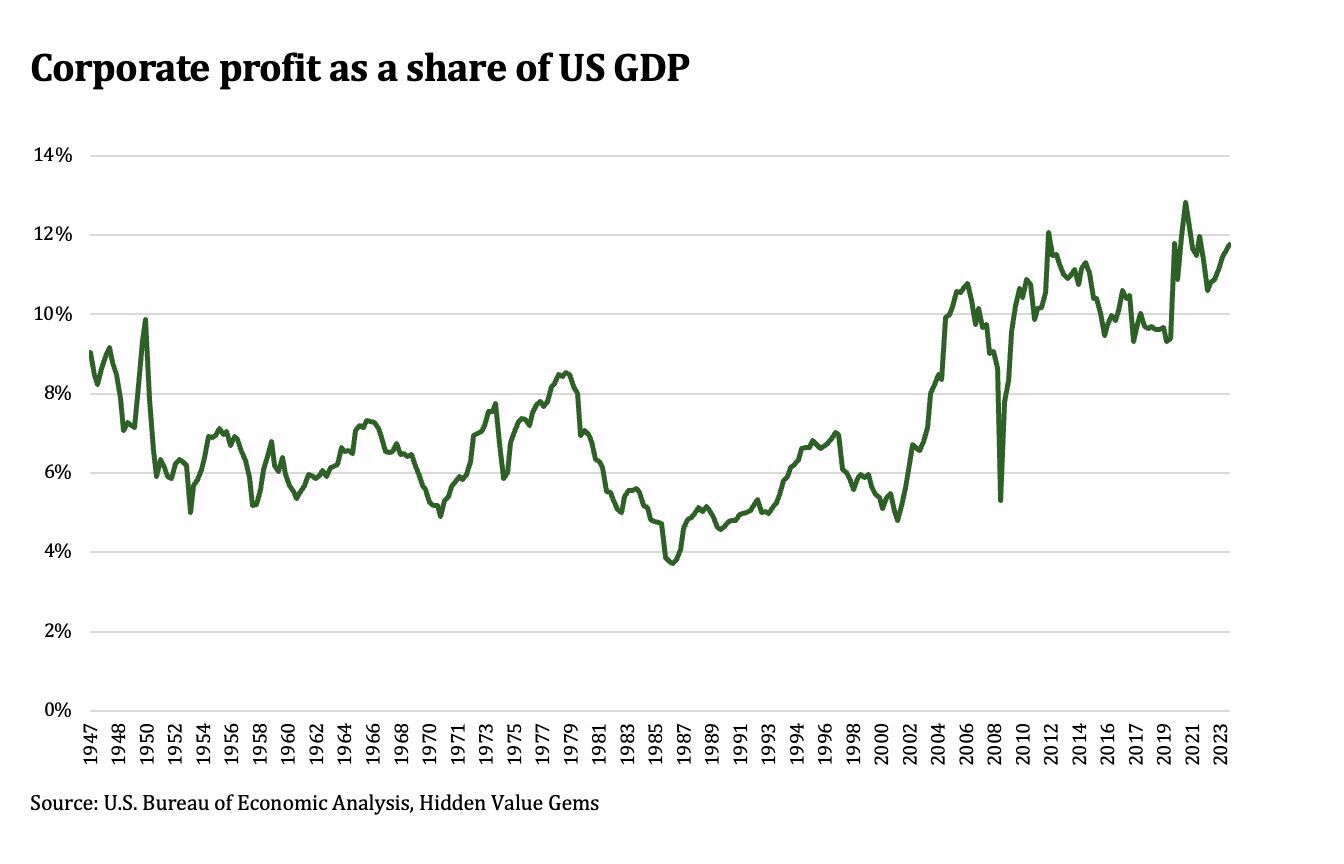

This theme is a more persistent inflation in the future. It can have significant consequences for investors. The last four decades have been, in many years, exceptional for the US market: interest rates were falling, as did the effective tax rate, while corporate profit margins were expanding.

Besides, thematic investing shifts your attention from what matters (business performance and returns on capital) to just ‘stories’.

With this disclaimer out, I would nevertheless take the risk of sharing a theme I expect to have long-term consequences for investors.

This theme is a more persistent inflation in the future. It can have significant consequences for investors. The last four decades have been, in many years, exceptional for the US market: interest rates were falling, as did the effective tax rate, while corporate profit margins were expanding.

One big driver behind this trend was low inflation. The factors behind it have been discussed many times: globalisation, market liberalisation, productivity growth.

What has not been discussed that often is whether these factors are still intact or have actually reversed and what that means for investors.

I can see at least 9 reasons why higher inflation will likely be a permanent feature for many years to come.

What has not been discussed that often is whether these factors are still intact or have actually reversed and what that means for investors.

I can see at least 9 reasons why higher inflation will likely be a permanent feature for many years to come.

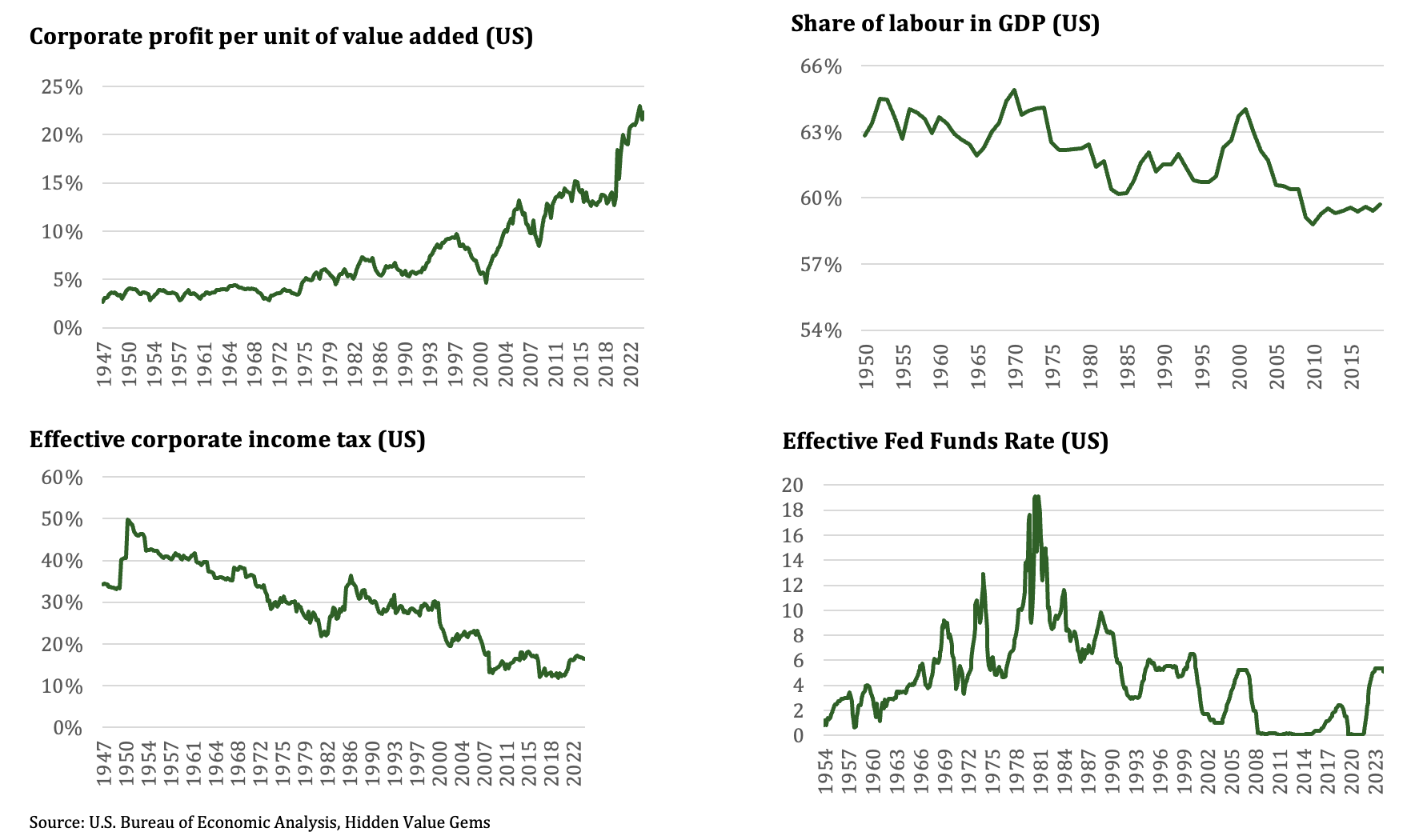

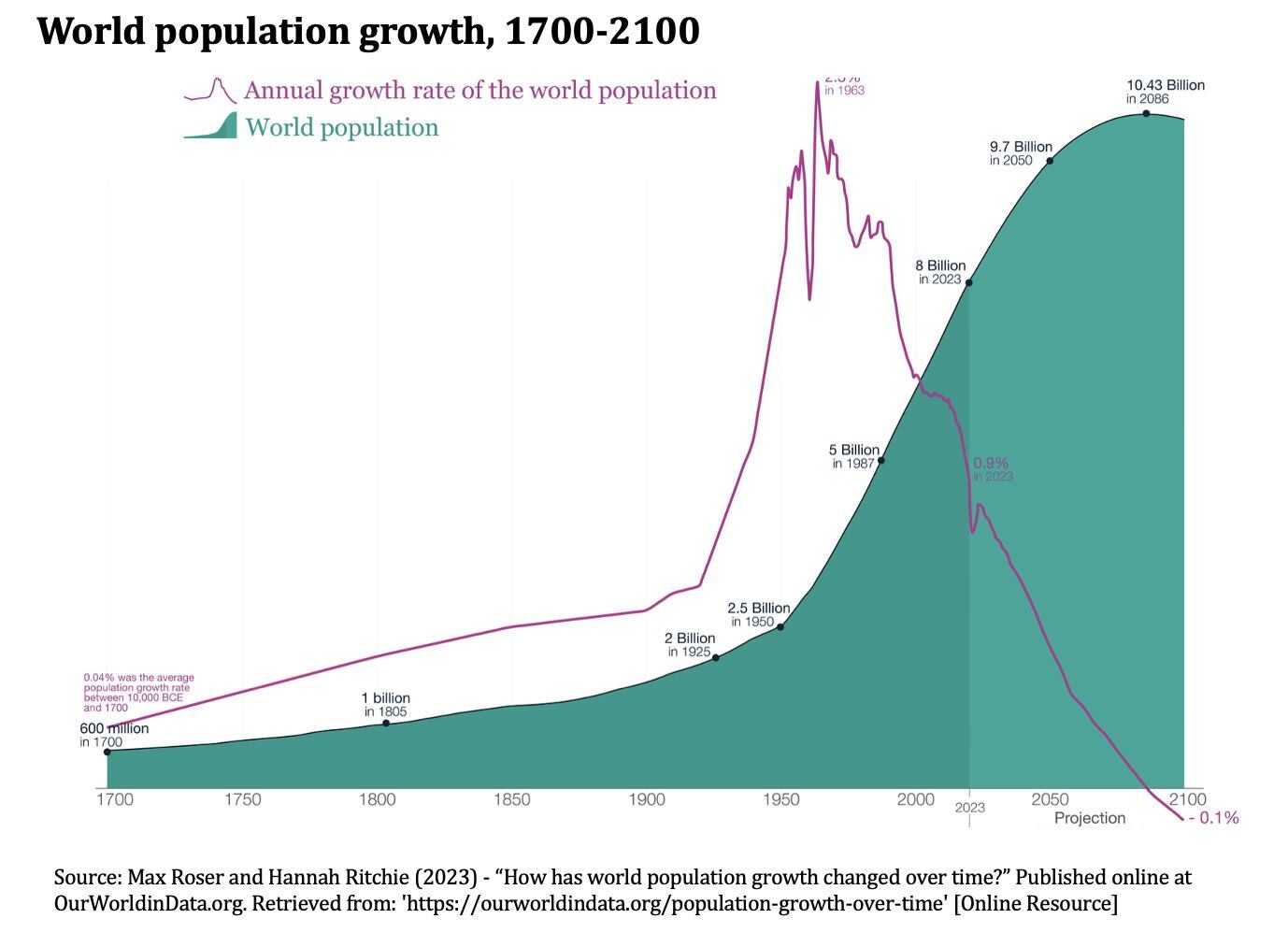

Reason 1. Falling birth rates

Global population growth has materially slowed down from the peak of 2% in the 1960s to less than 1% in 2023. In absolute terms, this means that we have passed the peak growth rates: in 1990, there were 92.8 million more people on the planet than in the previous year, but this incremental growth has since dropped to 64.7 million in 2021.

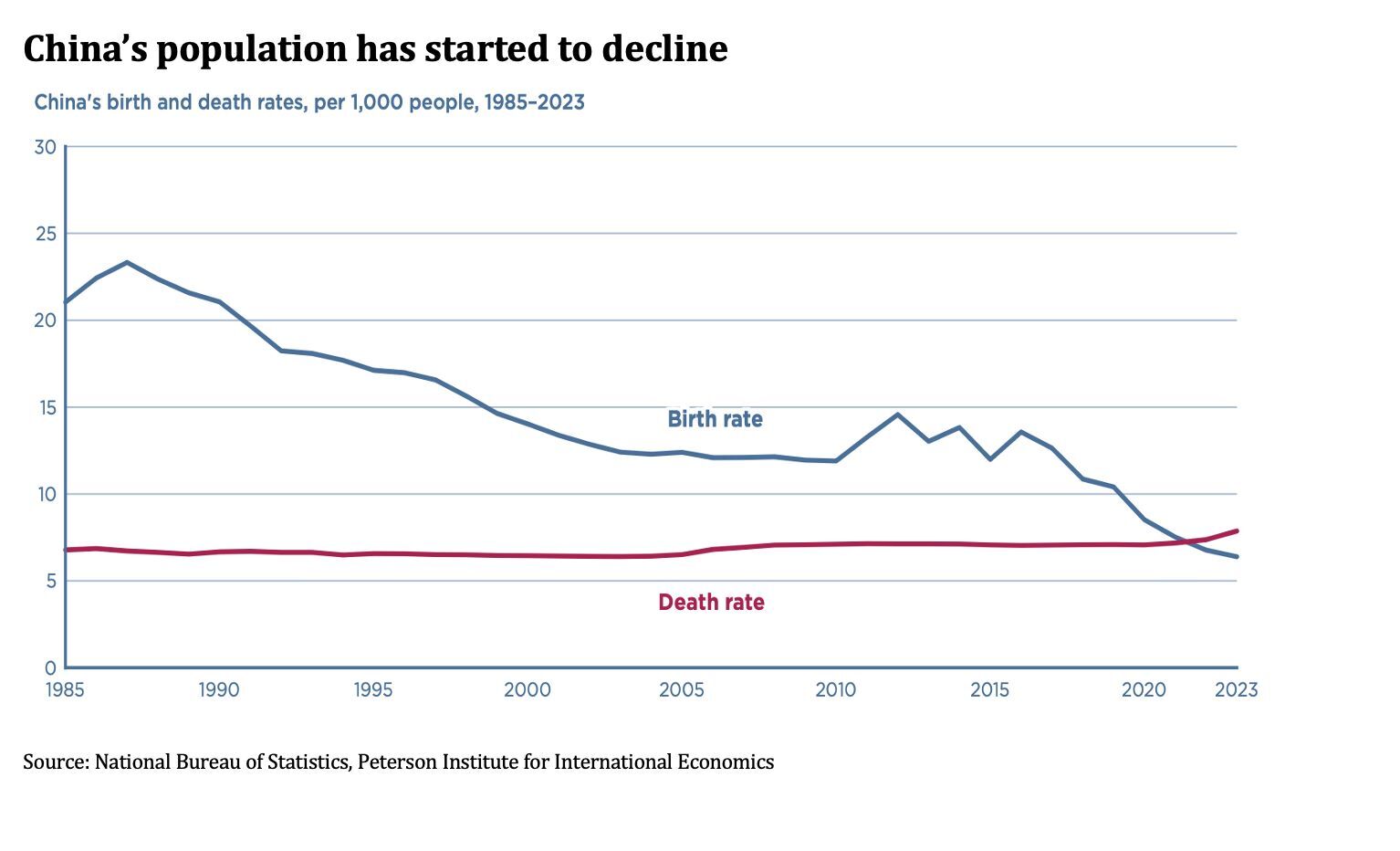

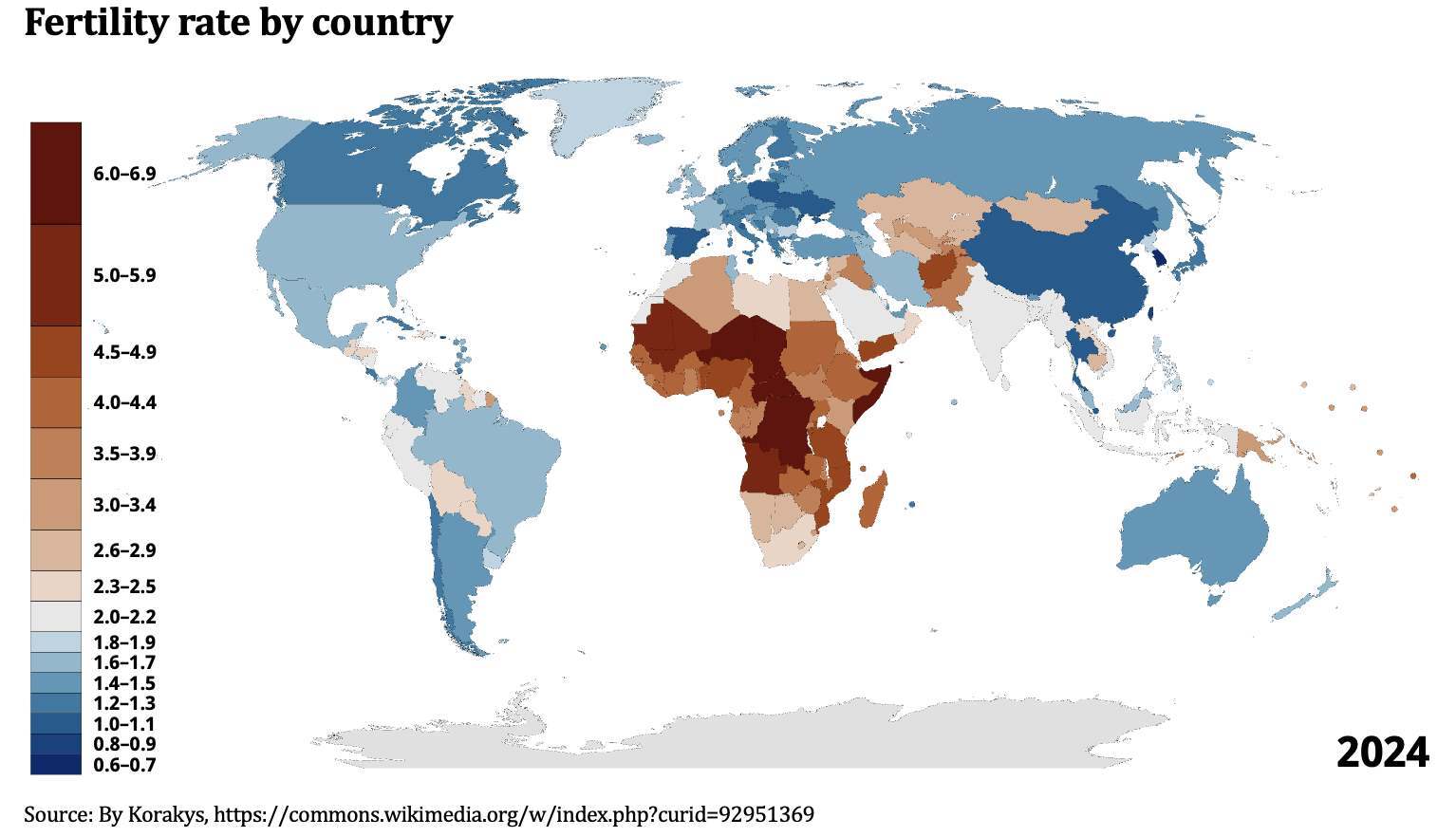

The core driver has been the falling fertility rate (number of children per woman), which has declined from 5.3 in 1963 to 2.3 in 2021. This level is close to the critical 2.1 rate, after which the population starts declining. Many large economies have already entered a de-population phase. China is the most prominent example. Its population has been in decline since 2022, shrinking by 2 million people last year. Other countries facing population decline are Japan, Korea, Italy, Ukraine, Russia and several others.

The lower the birth rate in a country, the less resources are available in its labour market making.

Reason 2. Ageing population

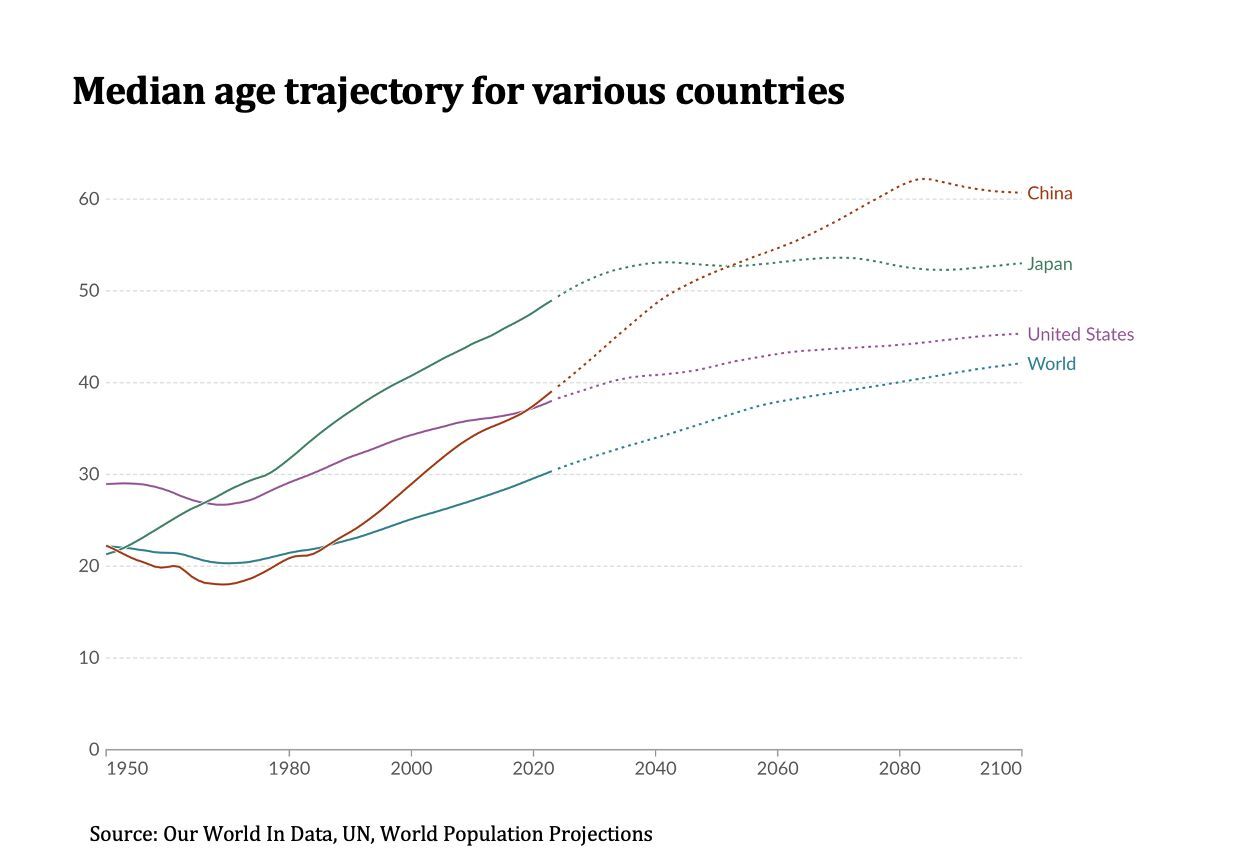

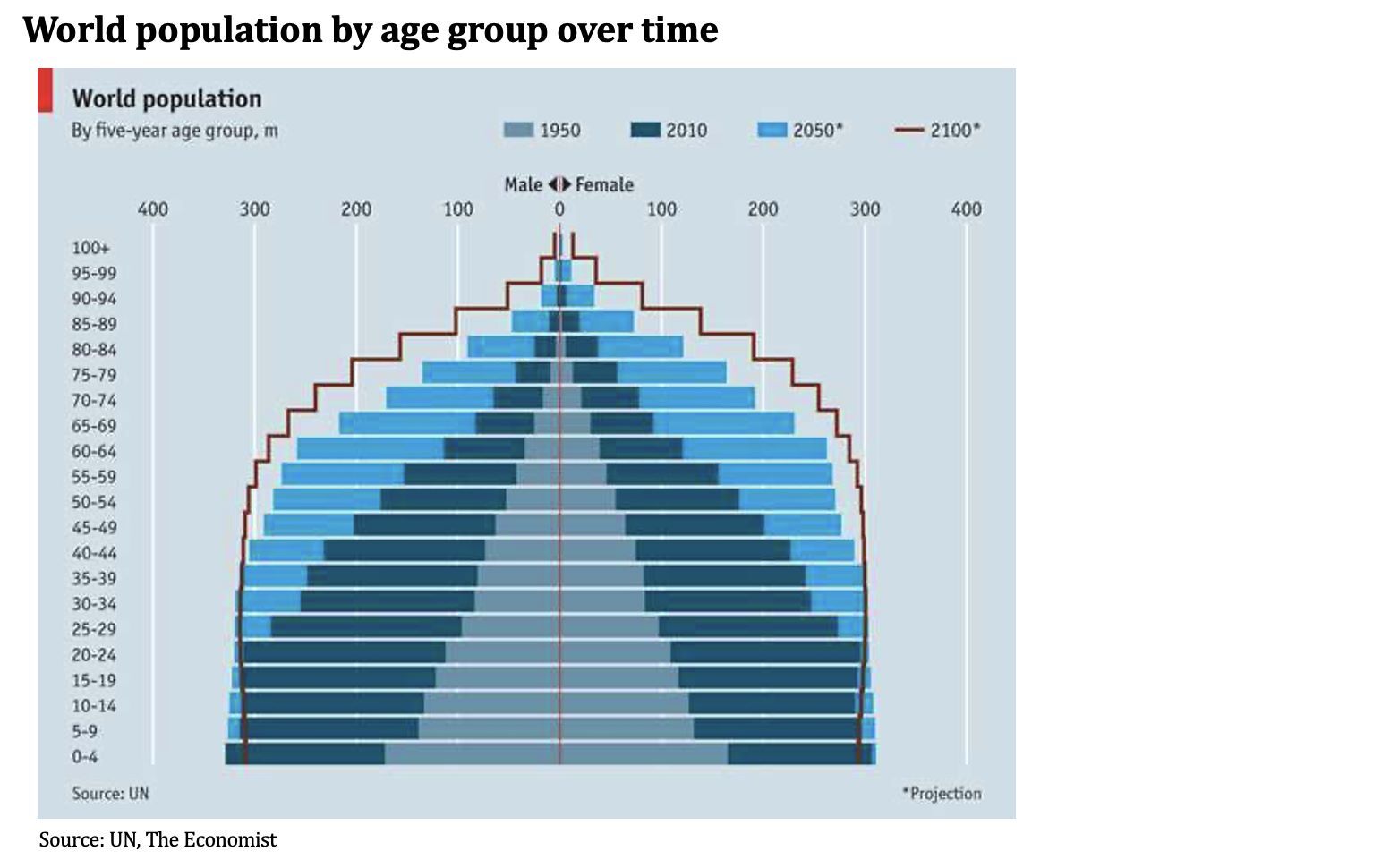

In addition to slowing the labour pool, many countries are now facing a higher dependency ratio as there are more retirees per worker today than 20-30 years ago. The average age of the population was just 22 years in 1950. It is now 30 years, and the UN expects it to reach 42 years by 2100. In most large economies, the age is much higher.

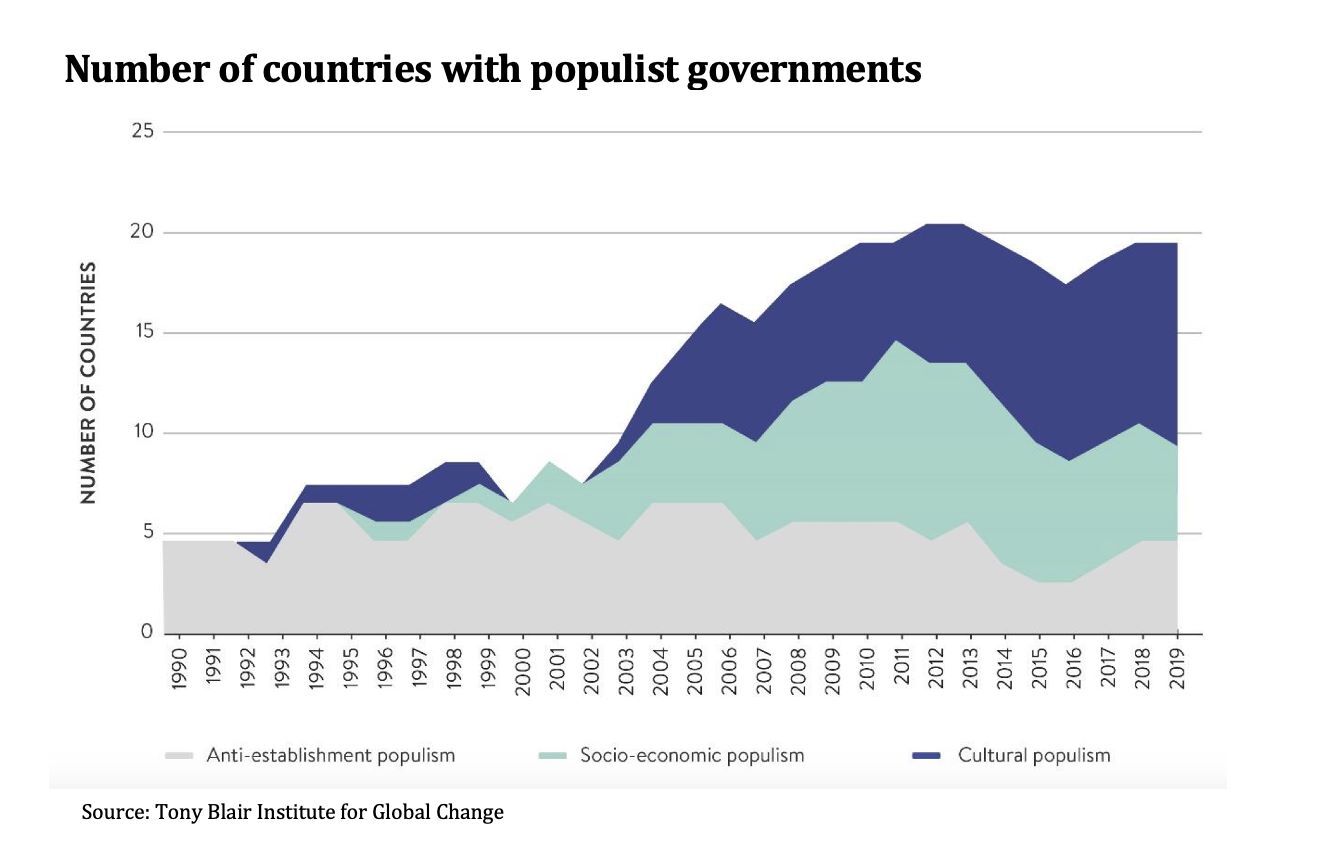

Reason 3. Populism, social agenda, unions

The radicalisation of politics started quite some time ago and it does not seem to stop. More people are willing to take more radical views with fewer standing in the middle. Historically, such periods have led governments to spend more and generally follow less conservative fiscal and monetary policy (the German experience in the 1920s is the most striking). This has inevitably led to higher inflation.

Most governments are bringing more social security payments like Universal Credit in the UK.

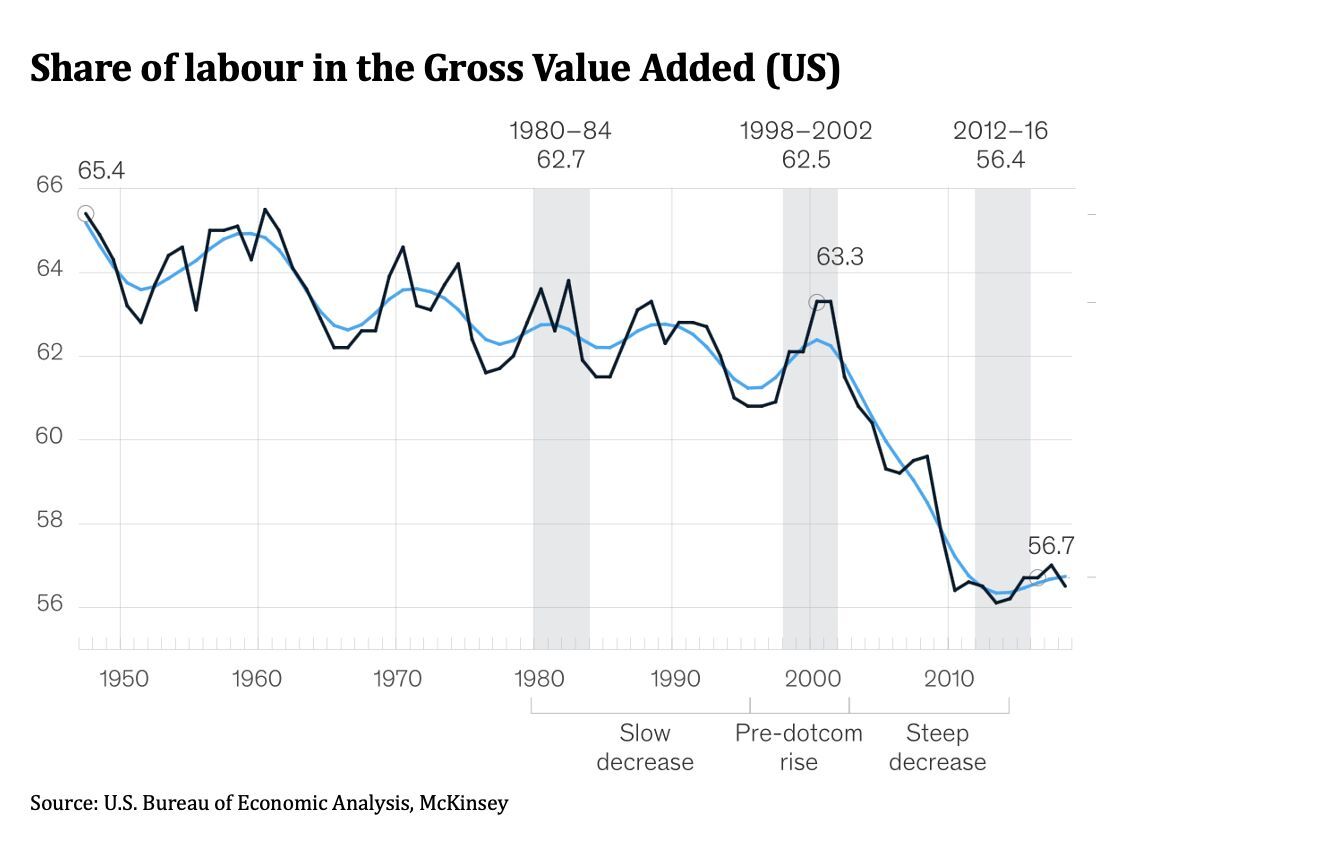

Unions are becoming more powerful, pushing for higher wages and more rights for workers.

In light of these developments, it is unlikely that corporate margins will stay at the historically high levels that were achieved recently.

Unions are becoming more powerful, pushing for higher wages and more rights for workers.

In light of these developments, it is unlikely that corporate margins will stay at the historically high levels that were achieved recently.

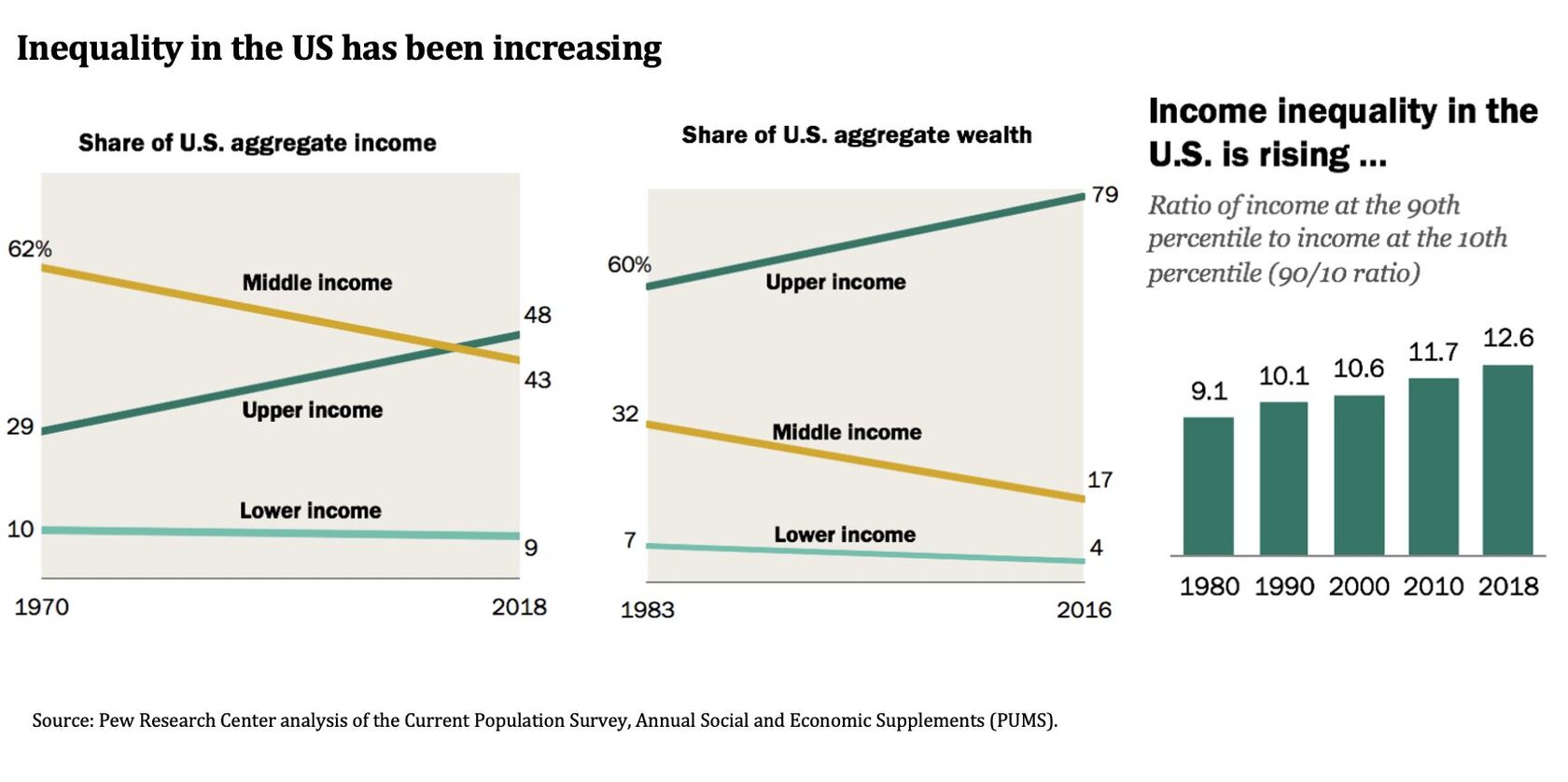

Reason 4. Rising inequality

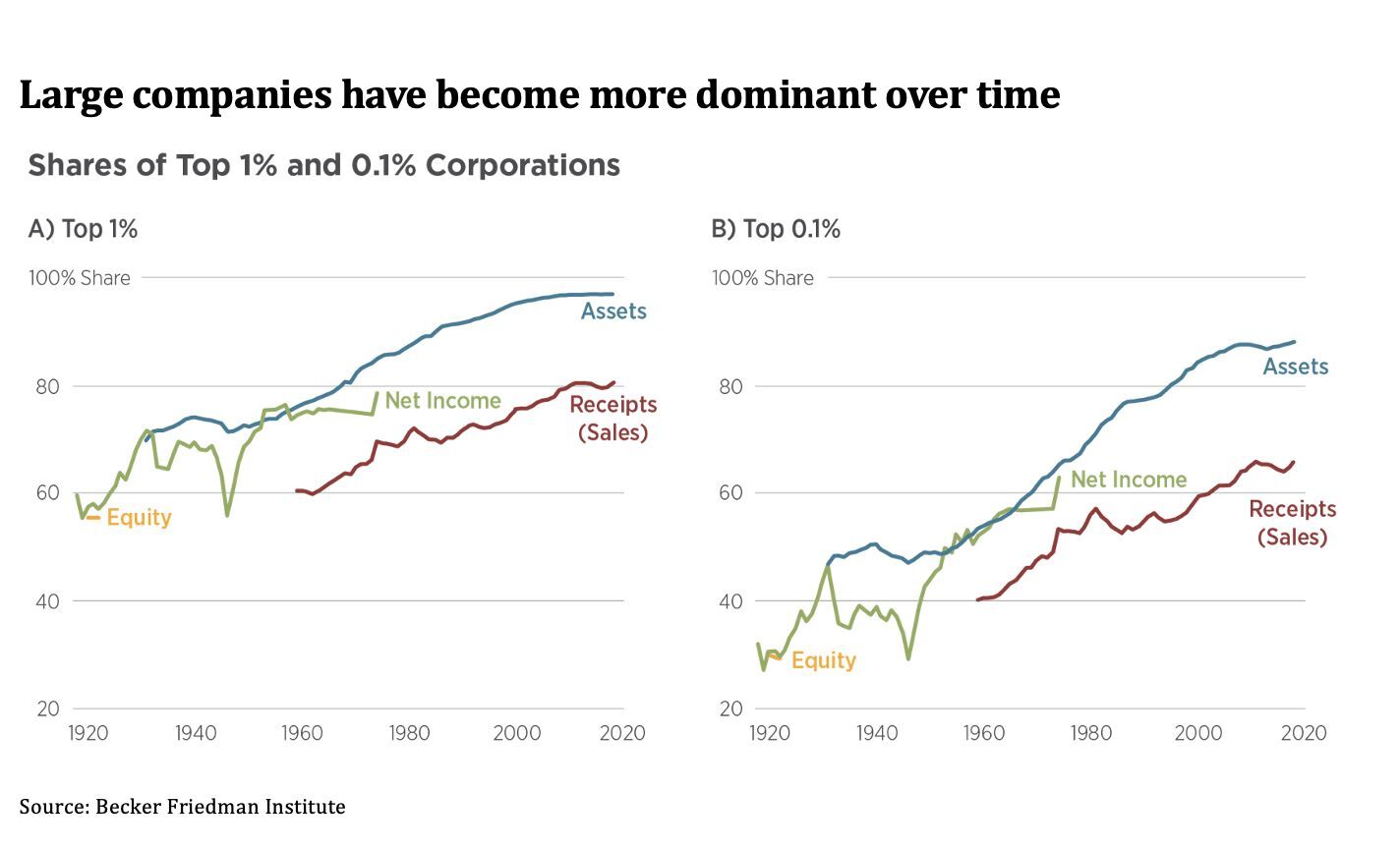

This issue has been discussed multiple times. The rich get richer faster as can be evidenced from the following charts. The trend has gotten especially clear since 2009, when low interest rates inflated asset prices, benefiting those who held them (shareholders, investors) at the expense of workers.

Reason 5. Government debt

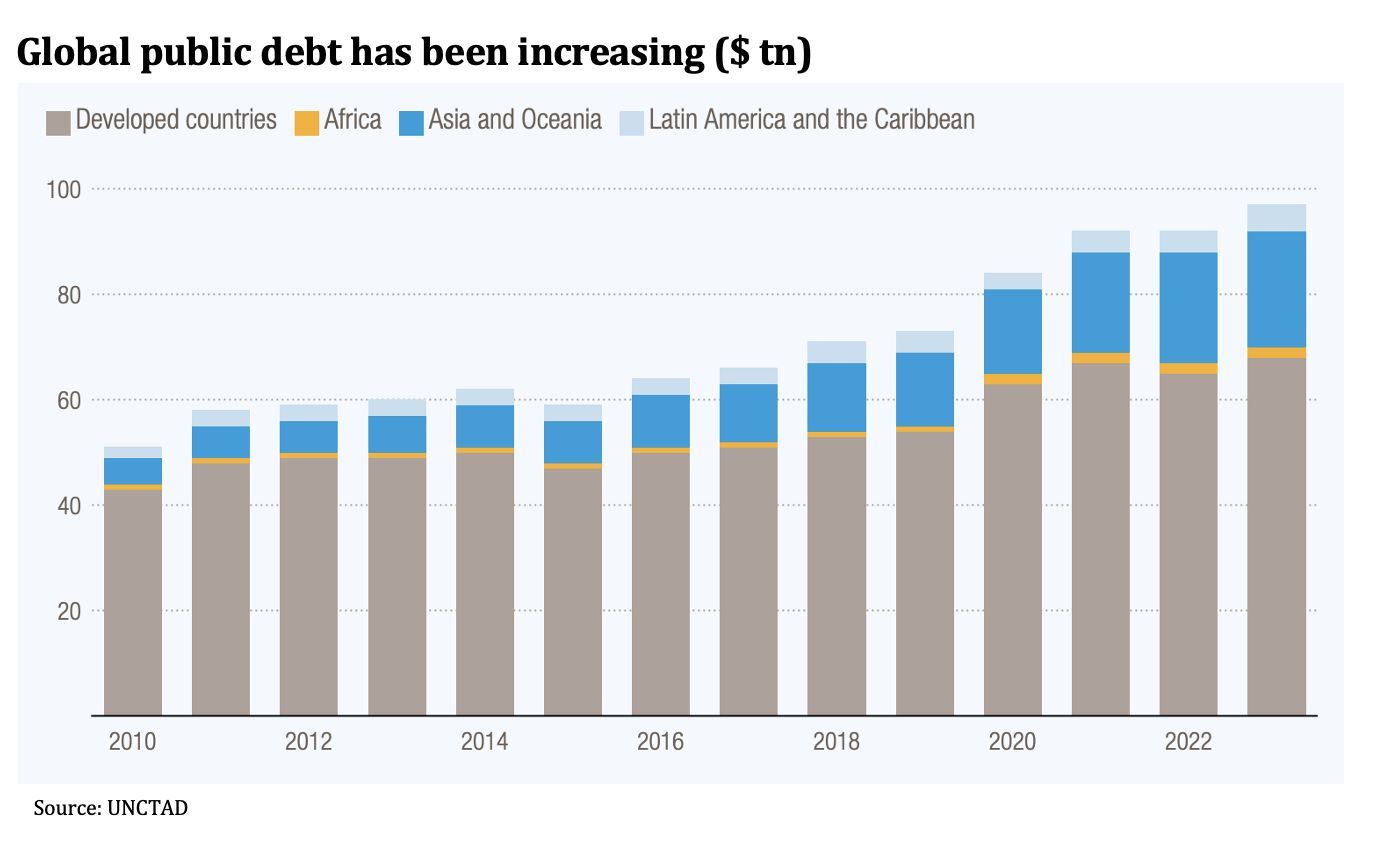

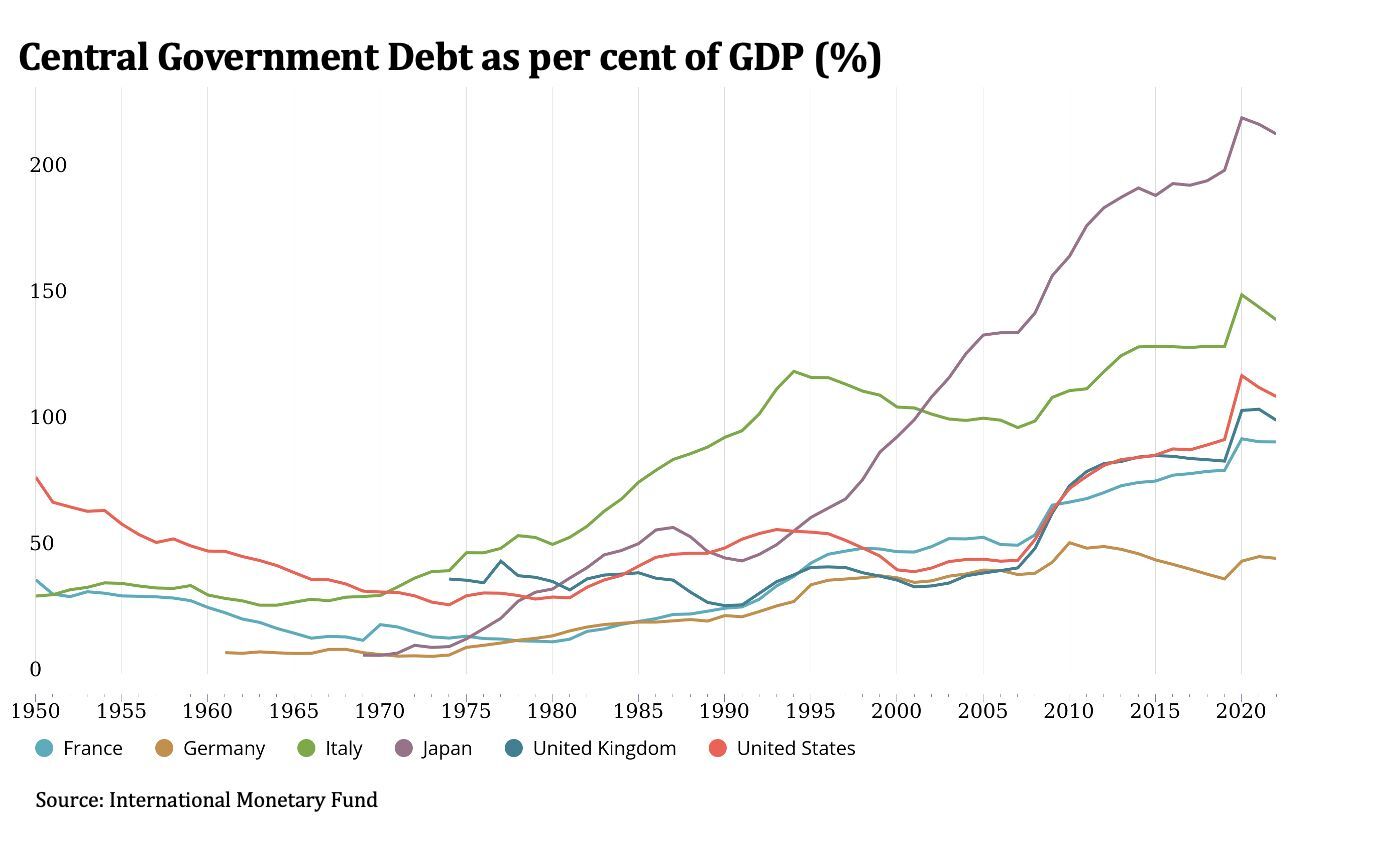

With few exceptions, government debt has risen relative to GDP, especially in large economies like the US. Global government debt has reached $100tn this year, accounting for 100% of the GDP.

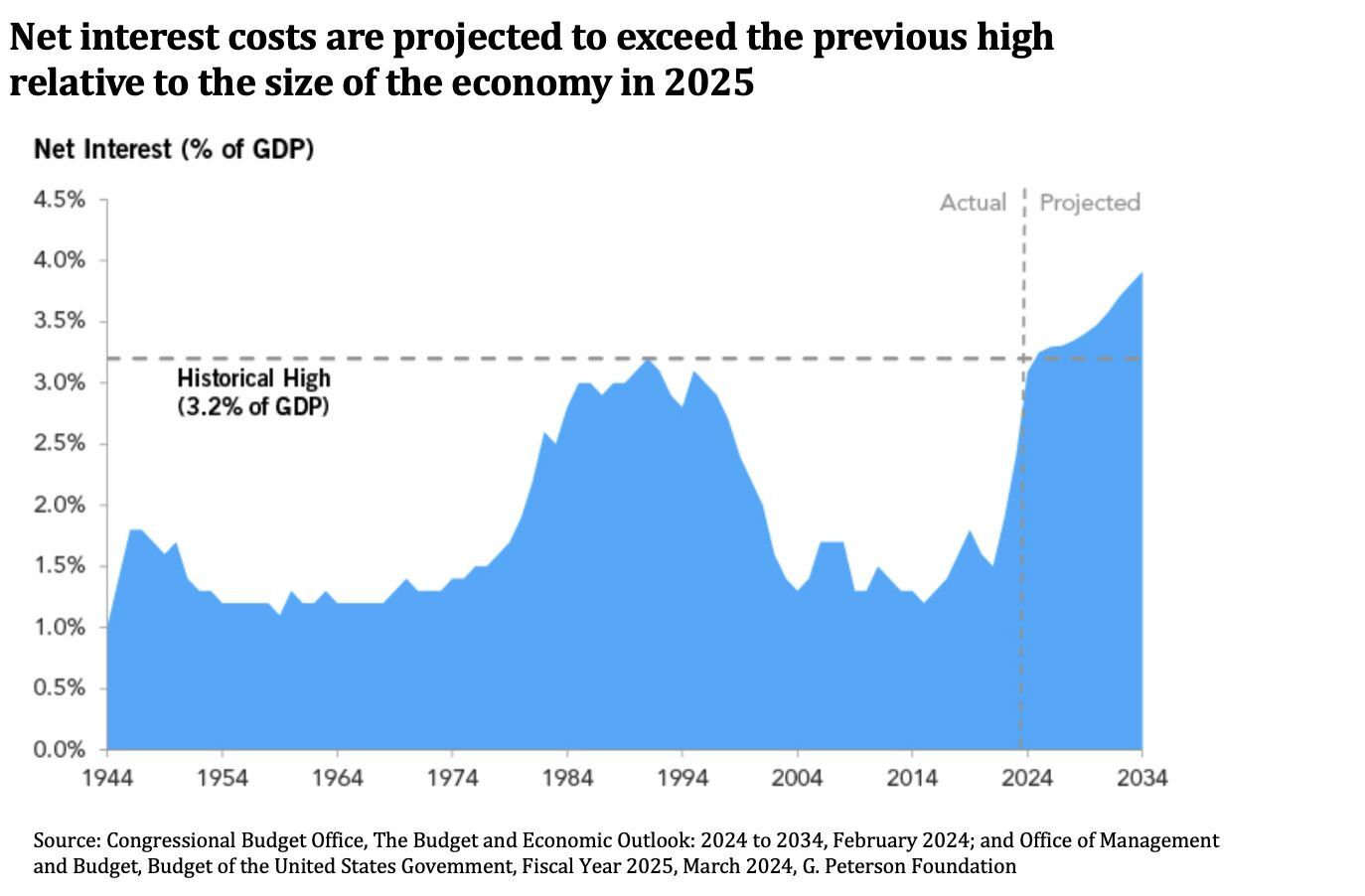

As interest rates have increased, servicing this debt will cost more and require higher government spending just for interest payments.

The US Federal government spent $658bn on net interest costs in 2023, representing 2.4% of the GDP. The total budget deficit in the same year was 6.2%, suggesting that 39% of the budget deficit was related to interest payments. More alarming is the projected budget spending for 2024. With the budget deficit estimated at 5.6% of GDP this year, the US government interest payments ($892bn) could account for about half of the deficit.

Reason 6. Military spending

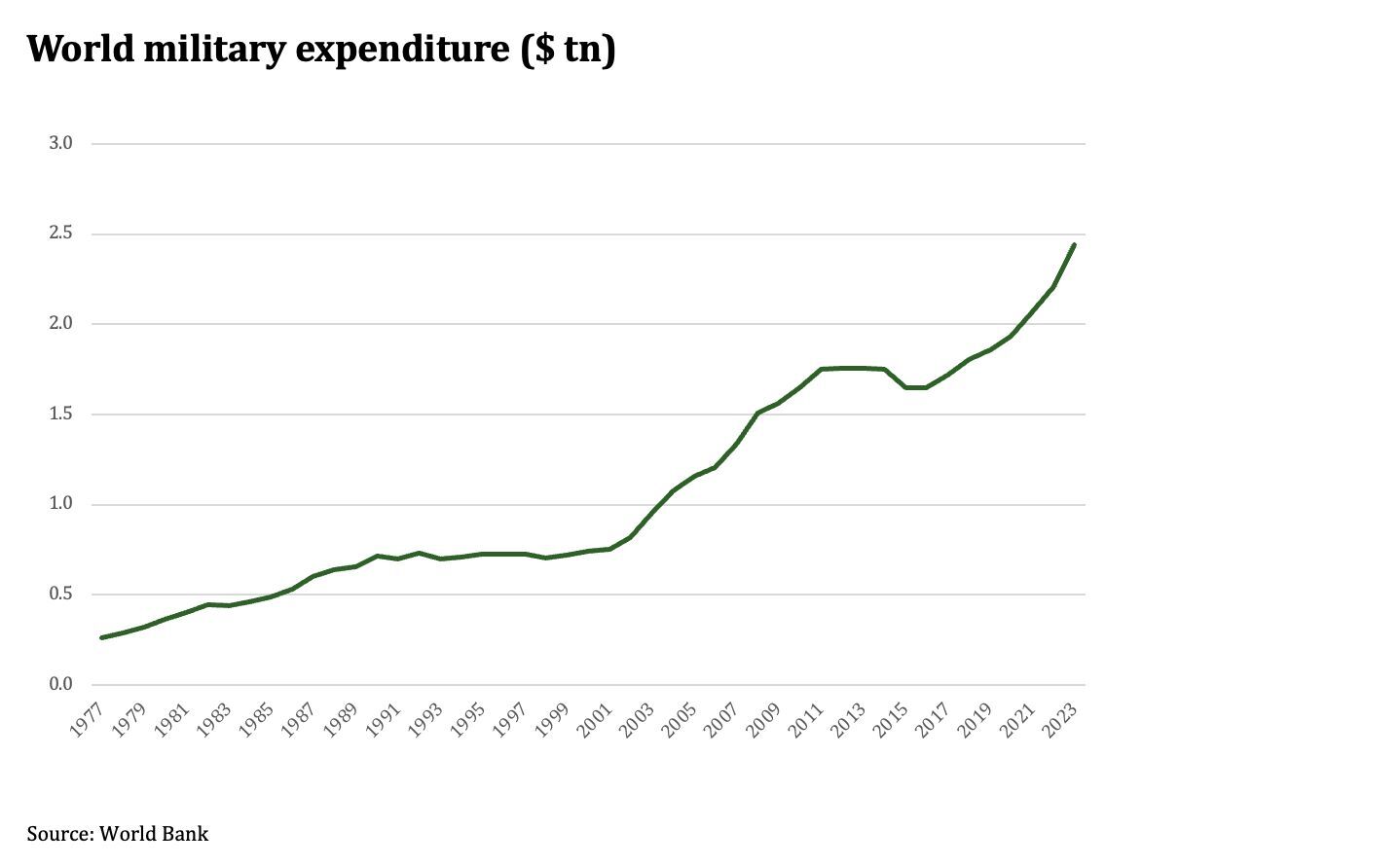

Higher debt and interest payments happen during growing military spending, especially in Europe. After the end of the Cold War, global military spending remained stable at $0.7tn. However, from 2000, defence expenditure started to rise and accelerated since 2022, increasing 18% in two years (2021-2023).

Military spending boosts demand in the economy, particularly for materials and creates more jobs, but it does not lead to higher economic output. More demand with the same supply eventually leads to higher prices.

Reason 7. Deglobalisation

With geopolitical tensions rising, companies are no longer willing to rely too much on offshore supply chains. This is partly driven by increasing prosperity in China, which pushes labour costs higher. The growing trend for ‘re-shoring’ and ‘near-shoring’ leads to higher spending on new facilities and supply chains. Without a corresponding increase in total output, such processes push expenditures and, consequently, inflation higher.

Often, national security concerns outweigh economic factors, leading companies to prefer higher costs over the vulnerability of their supply chains.

With higher inequality fuelling nationalistic and populist ideas, more trade barriers are emerging.

All this is pushing inflation higher.

Often, national security concerns outweigh economic factors, leading companies to prefer higher costs over the vulnerability of their supply chains.

With higher inequality fuelling nationalistic and populist ideas, more trade barriers are emerging.

All this is pushing inflation higher.

Reason 8. Higher barriers to entry, monopolisation of various sectors

As the economy becomes more driven by intangibles, traditional laws of diminishing returns do not always apply. Many sectors follow winner-take-all models, as businesses benefit from strong network effects and high barriers to entry. As a result, sector concentration has been increasing in many parts of the economy, as evidenced by the growing share of the top 10 companies in the global stock indices.

Reason 9. Energy transition

The world has broadly acknowledged the need to limit future emissions to avoid climate catastrophe. While there are still debates on the best strategy to achieve this, there is little doubt about introducing more renewable power and other apparent measures, such as building insulations and other energy-saving technologies, electrifying industrial processes, etc.

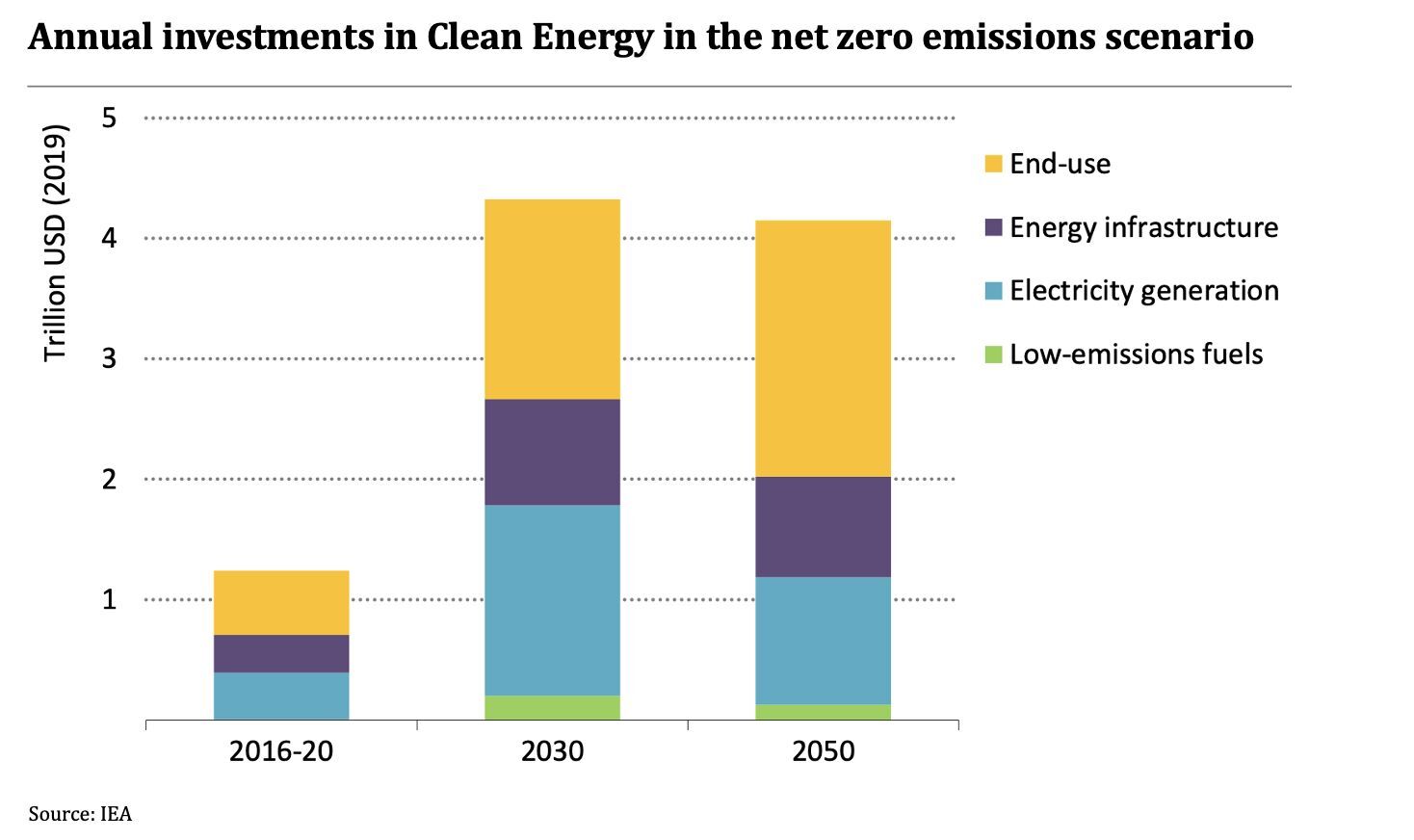

IEA does not always produce the most accurate forecasts, but as one of the leading authorities in the energy sector, its opinion counts. One of its latest reports on the energy transition estimated that the world would need to more than triple annual investments in clean energy to achieve net zero emissions by 2050 (see chart). This does not automatically mean higher inflation, but it does support lower prices even less.

IEA does not always produce the most accurate forecasts, but as one of the leading authorities in the energy sector, its opinion counts. One of its latest reports on the energy transition estimated that the world would need to more than triple annual investments in clean energy to achieve net zero emissions by 2050 (see chart). This does not automatically mean higher inflation, but it does support lower prices even less.

Implications for investors

The critical question is, what does this all mean for investors?

Firstly, the overall market returns may be materially lower than investors have experienced over the past 15 years. Higher inflation means higher interest rates and lower valuation multiples.

However, the opportunities for stock pickers may actually improve compared to recent times. As access to capital becomes more complicated, with higher interest rates and potential pressure on margins, companies with unsustainable business models will no longer be able to fund their operations and will have to leave.

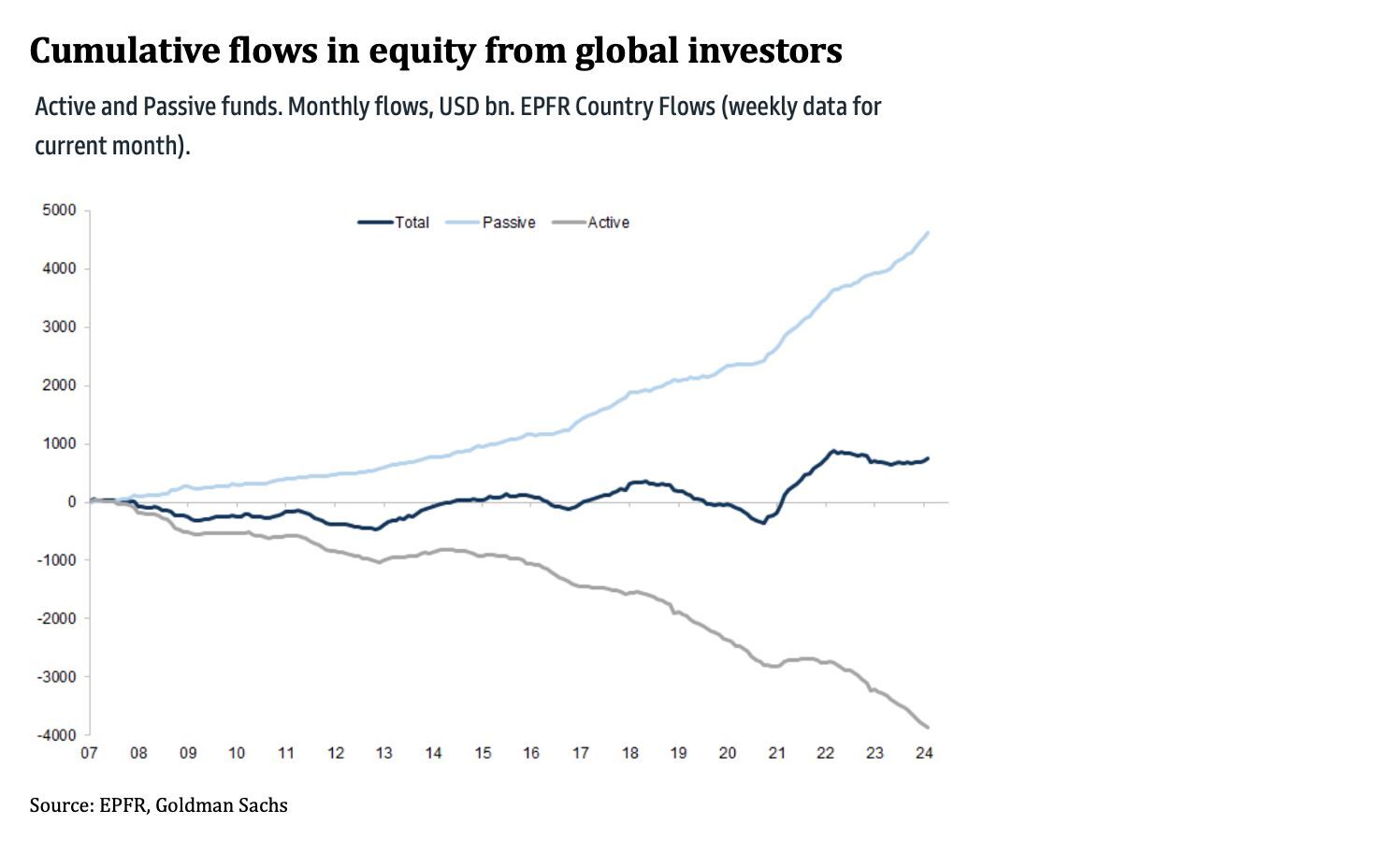

I expect more differentiation between outstanding and average businesses that mask themselves as good (e.g., by 'buying' growth through M&A, issuing new shares to fund loss-making operations and to pay employees, etc.). I do not think passive investing, which allocates more capital simply based on companies' market cap, will be able to differentiate between these different models. Or at least, a diligent investor should have an excellent opportunity to stay ahead of the curve.

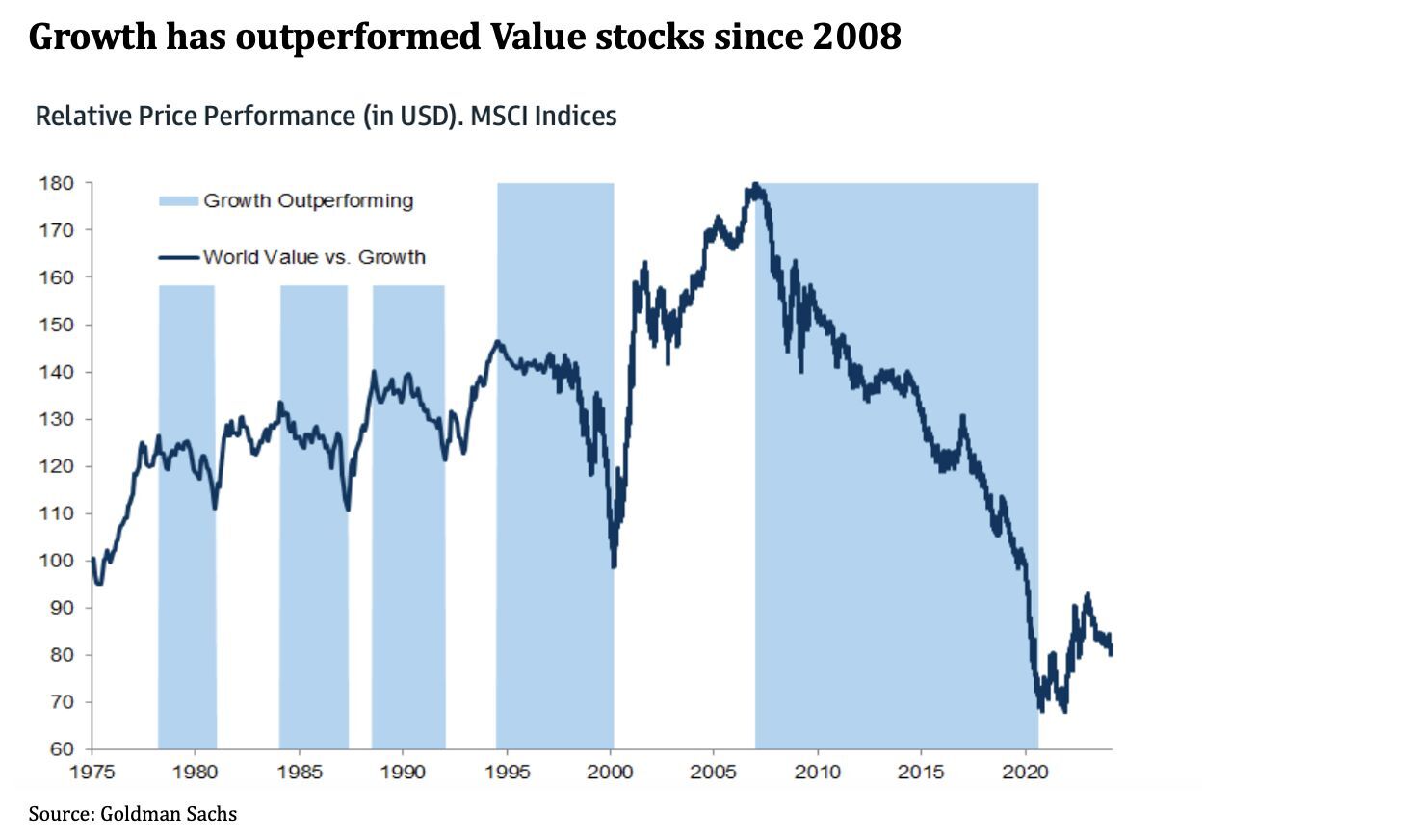

I am also sceptical about the prospects of passive investing. Many studies have tried to explain the phenomenon of passive investing leading to self-fuelled momentum partially driven by lower interest rates. If the rate environment looks materially different in the future, this may also break the current momentum in the so-called growth stocks.

Firstly, the overall market returns may be materially lower than investors have experienced over the past 15 years. Higher inflation means higher interest rates and lower valuation multiples.

However, the opportunities for stock pickers may actually improve compared to recent times. As access to capital becomes more complicated, with higher interest rates and potential pressure on margins, companies with unsustainable business models will no longer be able to fund their operations and will have to leave.

I expect more differentiation between outstanding and average businesses that mask themselves as good (e.g., by 'buying' growth through M&A, issuing new shares to fund loss-making operations and to pay employees, etc.). I do not think passive investing, which allocates more capital simply based on companies' market cap, will be able to differentiate between these different models. Or at least, a diligent investor should have an excellent opportunity to stay ahead of the curve.

I am also sceptical about the prospects of passive investing. Many studies have tried to explain the phenomenon of passive investing leading to self-fuelled momentum partially driven by lower interest rates. If the rate environment looks materially different in the future, this may also break the current momentum in the so-called growth stocks.

I would not embrace 'cheap' stocks, though, as ultimately, the price of a stock reflects business performance. There may be some upside from stock re-rating, but over the long term, most returns come from the growth of the business.

Despite common opinion, I also do not think asset-heavy businesses will do well in a higher-inflation scenario. Such companies usually face high reinvestment needs and may need to spend considerably more to maintain the same production base. Unless they are monopolies, they usually lack pricing power and cannot pass on higher capital costs to their consumers. As a result, their return on capital deteriorates.

Capital-light companies with unique products or services and high returns on capital that do not rely on external funding may actually do much better. Companies with strong capital allocation track records, like Berkshire Hathaway, should equally do well. Berkshire has been outbid by more aggressive private equity funds a few times recently, but it may find fewer competitors if financial conditions tighten. It has the additional benefit of owning large utility and railroad businesses with a better hedge against inflation.

AerCap could also benefit from higher inflation as its fleet can be leased at higher rates, reflecting higher new aircraft prices. Fixed long-term debt used to fund that fleet would also benefit its margins.

Companies with negative working capital, like Amazon or float (e.g. insurance), should equally do well in high inflation. Payment companies usually have low fixed costs to operate the system and naturally enjoy higher payment volumes with higher inflation (e.g. Corpay).

There will be other winners, but most importantly, many more opportunities for prudent active stock pickers.

Despite common opinion, I also do not think asset-heavy businesses will do well in a higher-inflation scenario. Such companies usually face high reinvestment needs and may need to spend considerably more to maintain the same production base. Unless they are monopolies, they usually lack pricing power and cannot pass on higher capital costs to their consumers. As a result, their return on capital deteriorates.

Capital-light companies with unique products or services and high returns on capital that do not rely on external funding may actually do much better. Companies with strong capital allocation track records, like Berkshire Hathaway, should equally do well. Berkshire has been outbid by more aggressive private equity funds a few times recently, but it may find fewer competitors if financial conditions tighten. It has the additional benefit of owning large utility and railroad businesses with a better hedge against inflation.

AerCap could also benefit from higher inflation as its fleet can be leased at higher rates, reflecting higher new aircraft prices. Fixed long-term debt used to fund that fleet would also benefit its margins.

Companies with negative working capital, like Amazon or float (e.g. insurance), should equally do well in high inflation. Payment companies usually have low fixed costs to operate the system and naturally enjoy higher payment volumes with higher inflation (e.g. Corpay).

There will be other winners, but most importantly, many more opportunities for prudent active stock pickers.