21 May 2023

Content:

I. Portfolio update

II. When to sell a stock

III. Exciting time for Value Investing?

IV. New additions to the Library

I. Portfolio update

II. When to sell a stock

III. Exciting time for Value Investing?

IV. New additions to the Library

I. Portfolio update

I sold all my position in EPAM on 8 May at about $242 price, taking a small profit of about 15% in 14 months.

Here are the reasons behind my decision.

Original thesis

My original thesis was based on the belief that the company’s business model would not be disrupted by the war in Ukraine. To remind, Ukraine, Belarus, and Russia accounted for 21%, 16% and 15% of EPAM’s total personnel, respectively. The three countries hosted 30,738 employees at the end of 2021.

By March 2022, the stock was down 71% since the start of 2022.

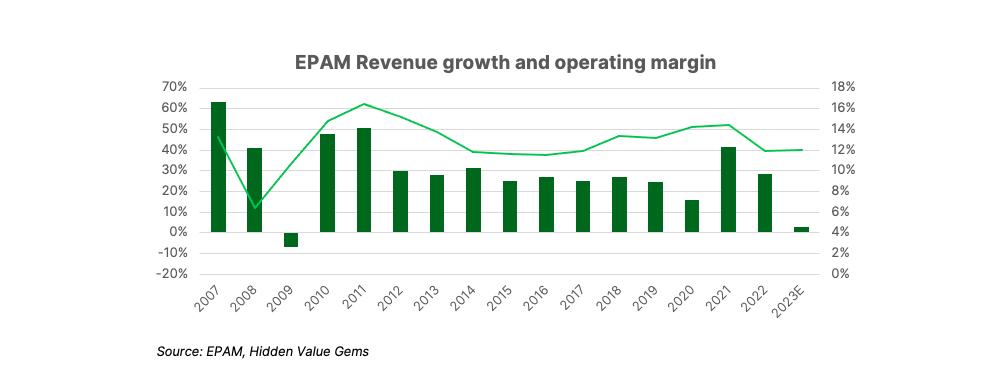

Yet, EPAM has been growing its revenue and earnings at 29% CAGR during 2010-21. On normalised earnings, the company was valued at about 15x PE multiple and a 10x PE based on 2025 earnings (assuming a 30% growth rate was maintained after 2022).

My edge was in having evidence that the EPAM operations were fairly robust.

I was proven right initially. In just six months, the stock was up over 100%.

By March 2022, the stock was down 71% since the start of 2022.

Yet, EPAM has been growing its revenue and earnings at 29% CAGR during 2010-21. On normalised earnings, the company was valued at about 15x PE multiple and a 10x PE based on 2025 earnings (assuming a 30% growth rate was maintained after 2022).

My edge was in having evidence that the EPAM operations were fairly robust.

I was proven right initially. In just six months, the stock was up over 100%.

You can read the entire thesis from 2022 here.

What has changed

While I cannot be 100% certain, there are signs that the business is not as robust as I thought. My original thesis was as follows: “A 30%-compounder available at 10-15x normalised PE due to issues that can be overcome.”

The new thesis is: “A business growing under 10% priced as a 30%-compounder.” I don’t have enough confidence to believe the business will return to its previous growth trajectory fast enough.

The new thesis is: “A business growing under 10% priced as a 30%-compounder.” I don’t have enough confidence to believe the business will return to its previous growth trajectory fast enough.

It looks like its personnel relocation led to some customer losses. The macro slowdown is definitely affecting EPAM.

I have not fully understood the business model, specific products, differentiating features, and why customers choose EPAM over alternative options. Without this knowledge, it becomes more of a gamble to me.

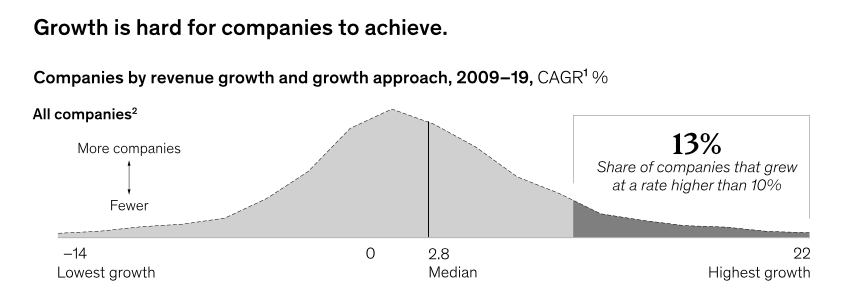

Finally, I should note that historically, very few companies can sustain sales growth above the 10% level for a long time. McKinsey estimates that the median annual growth rate for 5,000 companies they have studied was just 2.8%! And only 13% of companies grew faster than 10% during 2009-19. High growth is not a norm.

I have not fully understood the business model, specific products, differentiating features, and why customers choose EPAM over alternative options. Without this knowledge, it becomes more of a gamble to me.

Finally, I should note that historically, very few companies can sustain sales growth above the 10% level for a long time. McKinsey estimates that the median annual growth rate for 5,000 companies they have studied was just 2.8%! And only 13% of companies grew faster than 10% during 2009-19. High growth is not a norm.

Such growth is really an exception, and holding EPAM in light of the current slowdown would require me to have strong reasons to argue why EPAM is not like most other companies. I am afraid I lack the critical edge to do it.

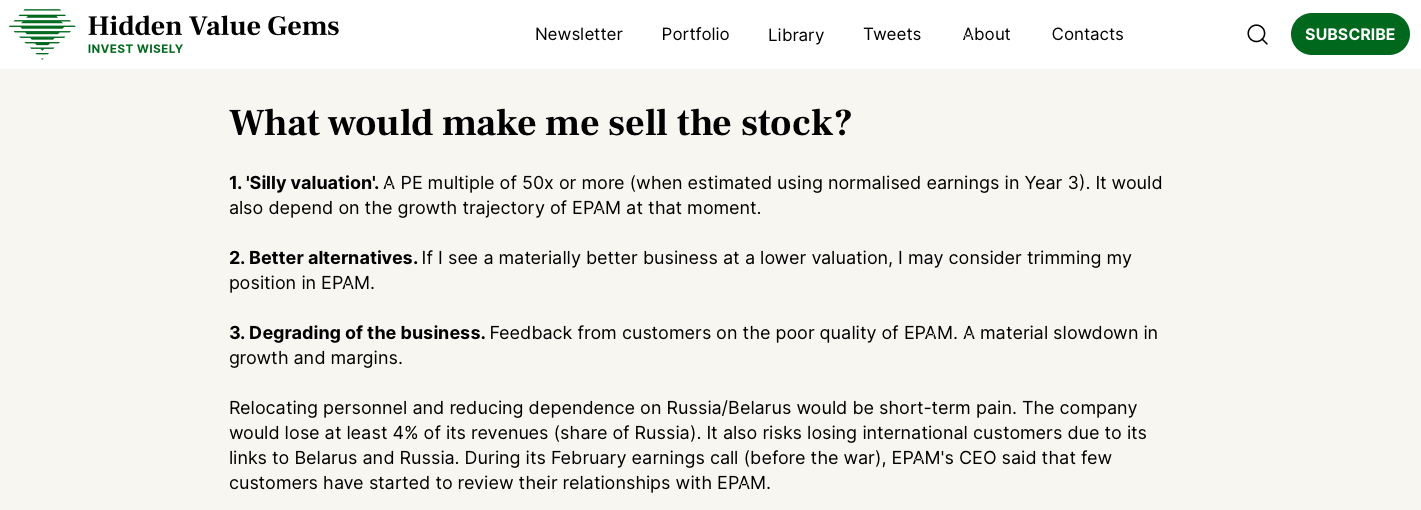

For reference, I listed eight conditions that would make me sell the stock in my original thesis.

The third condition was the Degrading of the business:

For reference, I listed eight conditions that would make me sell the stock in my original thesis.

The third condition was the Degrading of the business:

This discussion is a good reason to review the key points about when to sell a stock.

II. When to sell a stock

For me, the time to sell a stock is when the fundamental case has changed or when I find a new opportunity with better prospects and a more attractive price. The worst reasons are “When a stock reaches your price target” or “When you expect markets to go down.”

The concept of a price target assumes that you can predict the future and that it is constant.

Selling because you expect markets to go down is an equally lousy reason. It can be relevant when your personal circumstances are challenging (e.g. you lose a job in a crisis). But this is a forced sale that could be prevented by refraining from using excessive leverage and building enough savings during sunny days.

While this may sound easy, the reality, as always, is quite more complex.

The crux of the issue is knowing when the business fundamentals have really changed as opposed to a temporary headwind. Many biases prevent us from recognising the changes in the fundamental case. I have talked about some of them in the past (here and here) and plan to cover them in the future. My strong conviction is that it is more than just a lack of information but how we use available data and treat the new signals that lead us to sub-optimal decisions.

At the latest London Value Investor Conference that I attended this week, a famous value investor, David Einhorn, was asked how he decides when to sell a long position.

This is what he said:

The concept of a price target assumes that you can predict the future and that it is constant.

Selling because you expect markets to go down is an equally lousy reason. It can be relevant when your personal circumstances are challenging (e.g. you lose a job in a crisis). But this is a forced sale that could be prevented by refraining from using excessive leverage and building enough savings during sunny days.

While this may sound easy, the reality, as always, is quite more complex.

The crux of the issue is knowing when the business fundamentals have really changed as opposed to a temporary headwind. Many biases prevent us from recognising the changes in the fundamental case. I have talked about some of them in the past (here and here) and plan to cover them in the future. My strong conviction is that it is more than just a lack of information but how we use available data and treat the new signals that lead us to sub-optimal decisions.

At the latest London Value Investor Conference that I attended this week, a famous value investor, David Einhorn, was asked how he decides when to sell a long position.

This is what he said:

III. Exciting time for value investing?

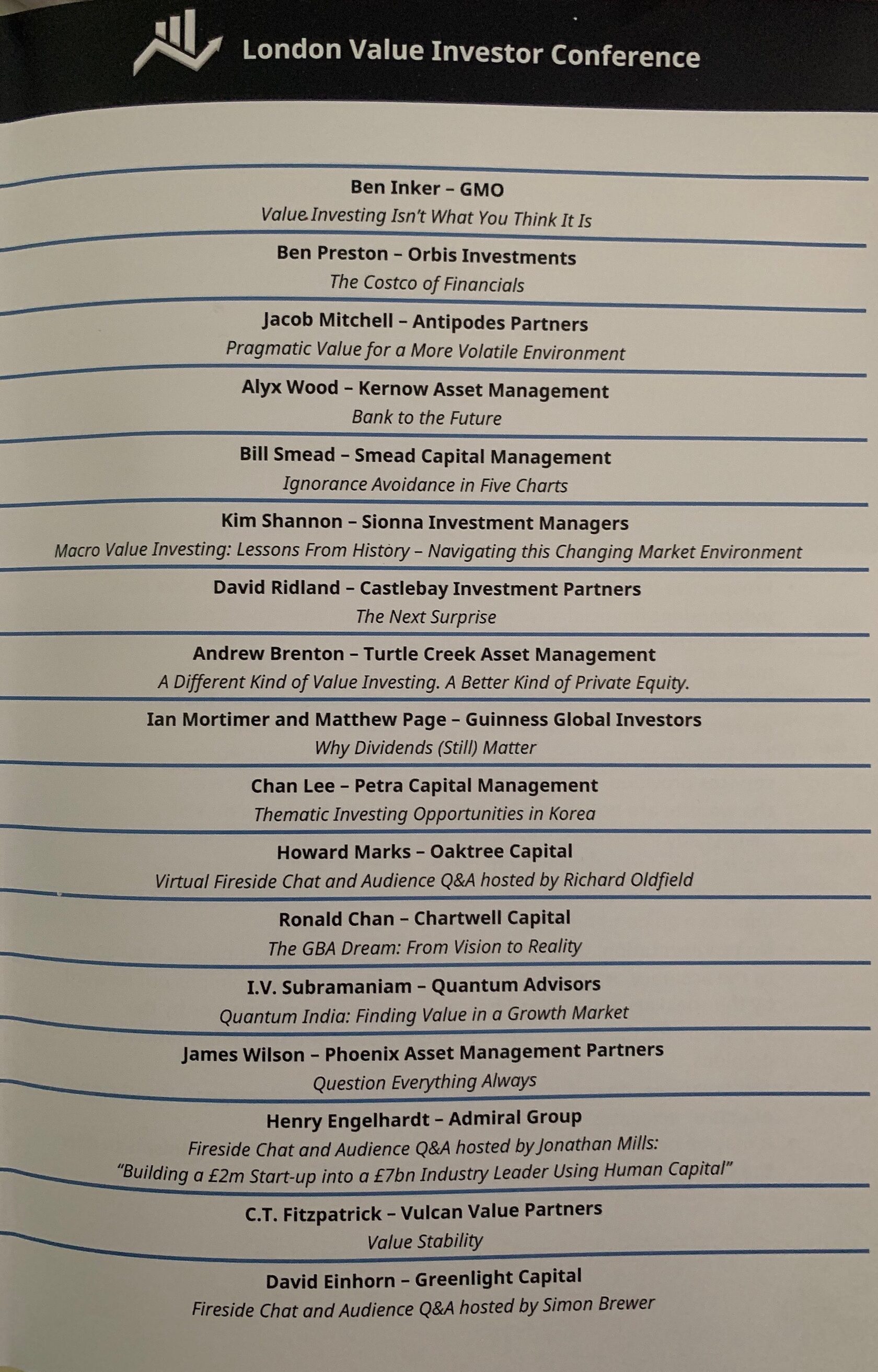

This was my fifth attendance at the London Value Investor Conference this year (never as a speaker so far, but who knows).

Apart from the price (about £900 or a little less if you book in advance), it is a good forum to learn about top picks from 17 speakers, hear their thoughts on the current market conditions and just meet new like-minded people. I need to work on the last point, though. Value investors are almost by default contrarian, who prefer to read and think rather than talk. So networking does not come easy, at least in my case, but I am working on it.

This year, the list of speakers was inspiring, with a few big names including Howard Marks, David Einhorn, and Ben Inker. I was also delighted to listen to a fire chat with Henry Engelhardt, the founder of Admiral Group, the UK's largest auto insurer, often referred to as the GEICO of Britain.

Apart from the price (about £900 or a little less if you book in advance), it is a good forum to learn about top picks from 17 speakers, hear their thoughts on the current market conditions and just meet new like-minded people. I need to work on the last point, though. Value investors are almost by default contrarian, who prefer to read and think rather than talk. So networking does not come easy, at least in my case, but I am working on it.

This year, the list of speakers was inspiring, with a few big names including Howard Marks, David Einhorn, and Ben Inker. I was also delighted to listen to a fire chat with Henry Engelhardt, the founder of Admiral Group, the UK's largest auto insurer, often referred to as the GEICO of Britain.

Here are some common themes flagged at the conference:

1. Most participants agreed we were in a new era of permanently high inflation and interest rates. This is a huge change compared to the past 40 years.

2. Such conditions bode well for commodities, including oil & gas, metals and agricultural products.

3. ESG and a long period of under-investment make the energy sector particularly interesting, especially in light of major capital allocation shift among corporates (from drilling to buybacks).

4. Canada was mentioned a few times as a market that was traditionally valued at a discount to the US and with a large number of commodity producers.

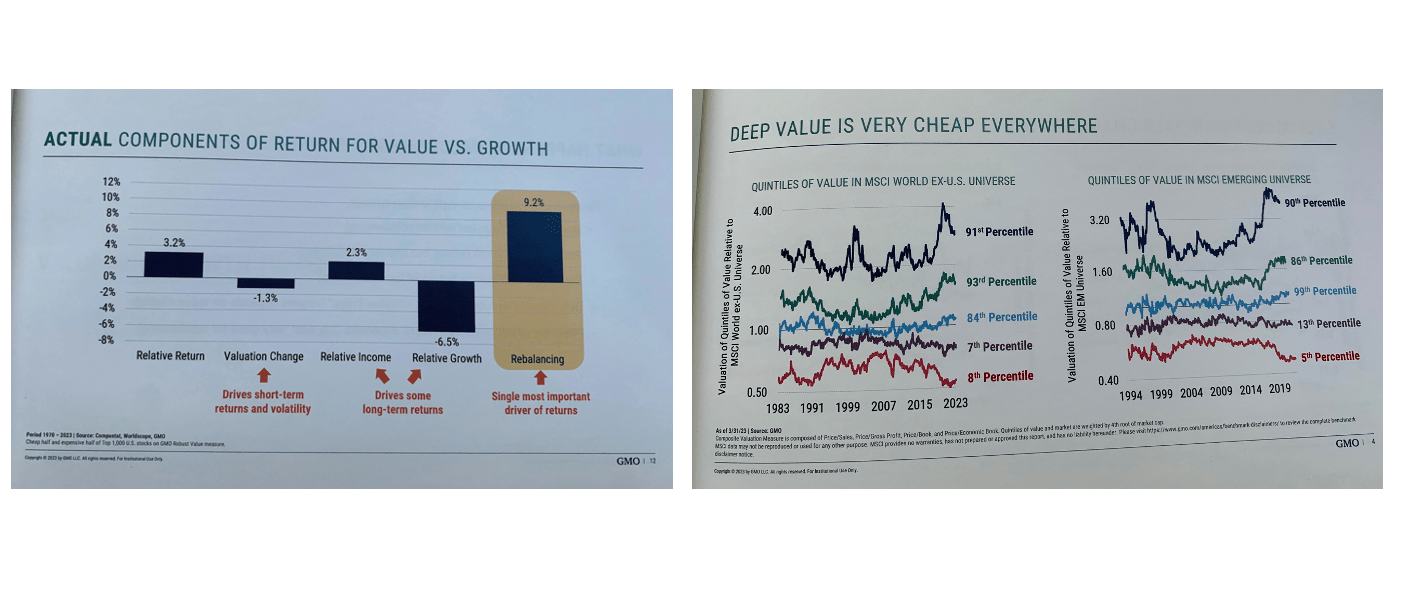

5. ‘Shallow value’, the stocks that are just a little cheaper than the market, is not cheap enough, according to Ben Inker, co-head of the Asset Allocation team at GMO. Two messages stuck with me from his presentation.

1. Most participants agreed we were in a new era of permanently high inflation and interest rates. This is a huge change compared to the past 40 years.

2. Such conditions bode well for commodities, including oil & gas, metals and agricultural products.

3. ESG and a long period of under-investment make the energy sector particularly interesting, especially in light of major capital allocation shift among corporates (from drilling to buybacks).

4. Canada was mentioned a few times as a market that was traditionally valued at a discount to the US and with a large number of commodity producers.

5. ‘Shallow value’, the stocks that are just a little cheaper than the market, is not cheap enough, according to Ben Inker, co-head of the Asset Allocation team at GMO. Two messages stuck with me from his presentation.

- ‘Deep value’ is really cheap today by all historical measures. As Ben put it, “this is at least 1-in-20 event.” And this is true across the world.

- The critical driver of returns of a value portfolio is ‘rebalancing’ when you systematically sell stocks that are not cheap and buy much cheaper alternatives. One of Ben’s conclusions was that “Value is not a buy-and-hold cheap stocks activity”.

IV. New materials added to the Library

Some housekeeping before I finish this note.

Here are the five new items that I have recently added to the Library:

Here are the five new items that I have recently added to the Library:

- Stan Druckenmiller presentation on the fiscal challenges faced by the US and implications for investors

- A collection of speeches, letters and interviews by Charlie Munger since 1978 (1,192 pages)

- Notes from Joel Greenblatt’s Class at Columbia Business School

- A free copy of Ed Yardeni’s book “In Praise of Profits”

- McKinsey Problem Solving Test (with answers)

Thank you for reading this piece. I hope it was useful. Please consider sharing it with your friends who may also benefit from this.