15 October 2023

Today’s post is about a practical strategy that can boost your investment returns in certain situations. It is straightforward and requires no human judgment.

Can a range-bound stock generate 186% gains?

Let me ask you if you would invest in the following company (let’s call it Company A).

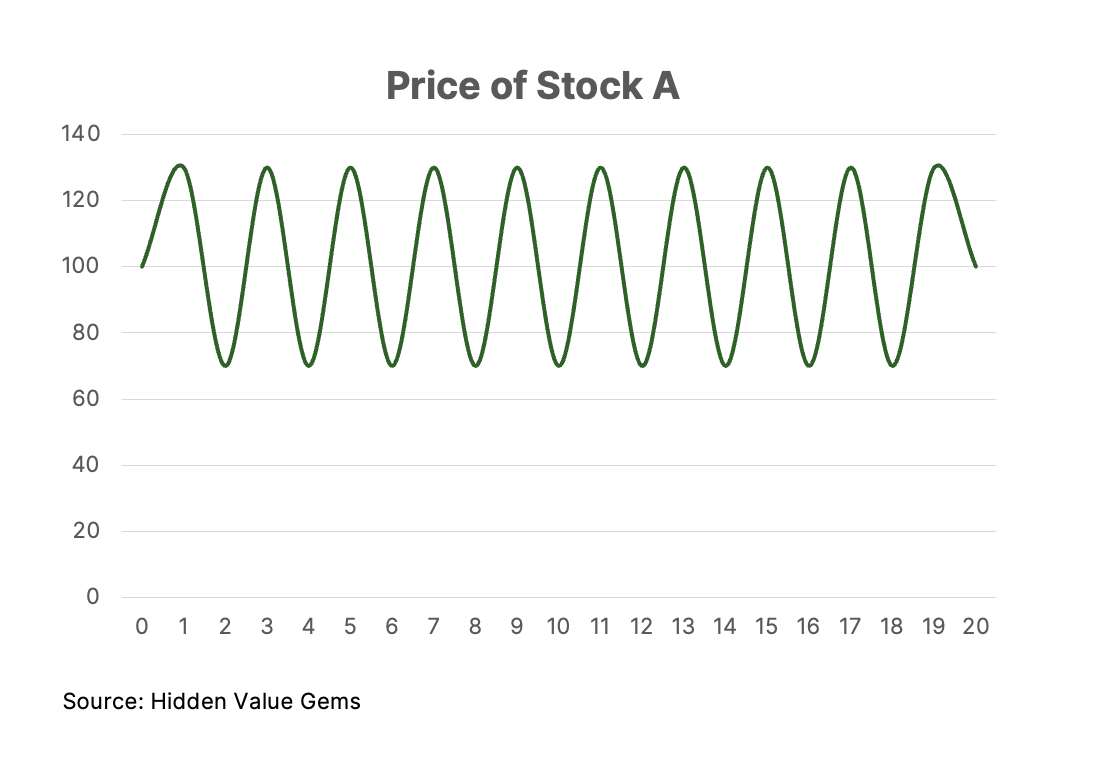

The stock has been range-bound for 20 years, stuck between $70 and $130. You can also think about the performance of an underlying business in a similar way (its sales and profits were fluctuating without a clear trend).

“Such a stock could attract a ‘speculator’, not a true long-term investor”, - a value investor inside you may have commented. (A ‘specular’ is a curse word among value investors who use it to refer to those trying to anticipate the next price move of an asset. By the way, I suspect there are a few such ‘speculators’ among value investors).

Now, have a look at the following chart, which shows the change in the value of a portfolio that is partially invested in such a security.

“Such a stock could attract a ‘speculator’, not a true long-term investor”, - a value investor inside you may have commented. (A ‘specular’ is a curse word among value investors who use it to refer to those trying to anticipate the next price move of an asset. By the way, I suspect there are a few such ‘speculators’ among value investors).

Now, have a look at the following chart, which shows the change in the value of a portfolio that is partially invested in such a security.

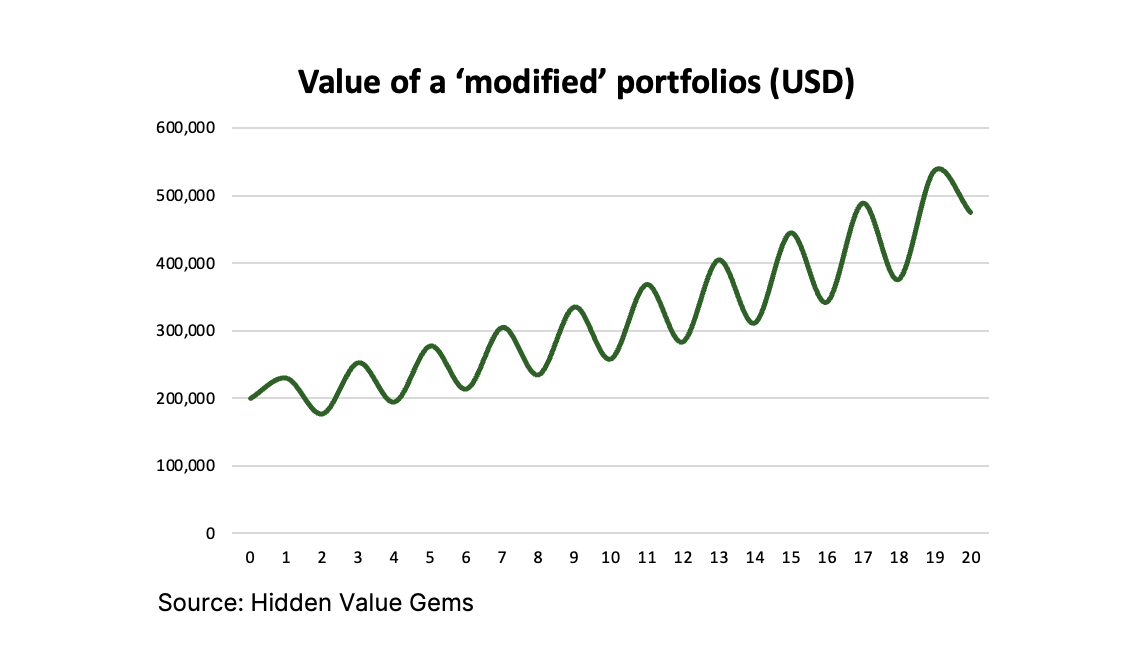

You may wonder what else is in the portfolio. The answer is Cash. This magic portfolio has a 50% weight in cash and another 50% in this one volatile stock.

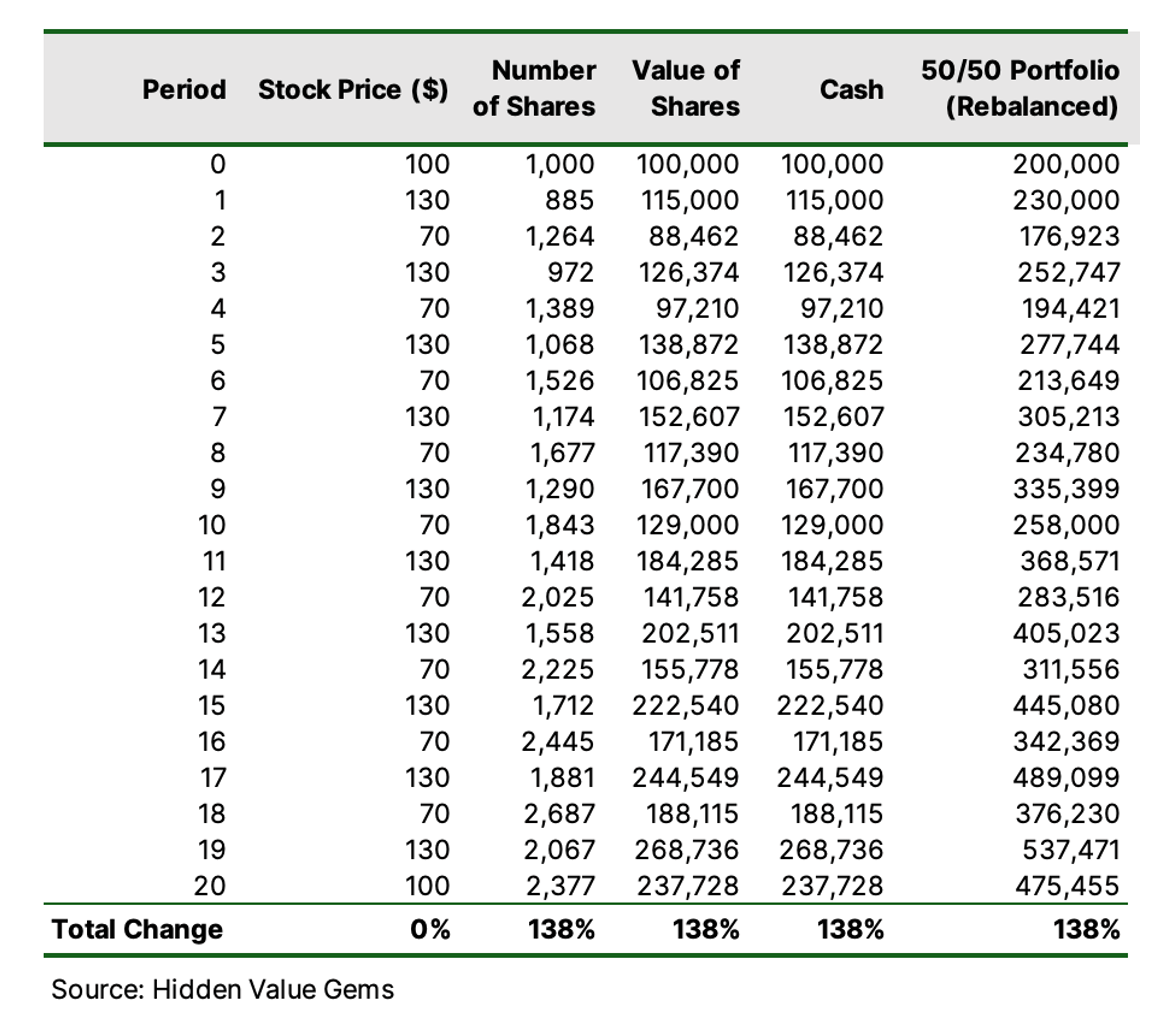

The secret behind this spectacular performance is a very basic strategy. At the start, the fund is invested equally in stocks and cash (50/50). Then, at the end of each period, the portfolio is rebalanced back to 50/50.

So, if the price of a stock goes up 30% (to $130), the weight of equity in the portfolio rises to 57%, while cash drops to 43%. The strategy would sell 115 shares (out of 1,000) for $130. The value of stock holdings will then be $115,000, the same as cash.

In the next period, the stock drops to $70. The market value of our equity holdings declines to just $61.9k. while the overall portfolio is now $176.9k (compared to $230k before).

We have to buy more shares this time. To match equity and cash, we buy 379 shares at $70, increasing the value of our stocks to $88.5k.

The process continues each time, rebalancing shares and cash by either selling some shares or buying more of them.

Note that we buy more shares at a lower price without doing any valuation work. We also sell more shares at a higher price, again disregarding P/E or other metrics.

After 20 iterations, the value of our portfolio rises to $475.5k, gaining 138% (2.4x).

The secret behind this spectacular performance is a very basic strategy. At the start, the fund is invested equally in stocks and cash (50/50). Then, at the end of each period, the portfolio is rebalanced back to 50/50.

So, if the price of a stock goes up 30% (to $130), the weight of equity in the portfolio rises to 57%, while cash drops to 43%. The strategy would sell 115 shares (out of 1,000) for $130. The value of stock holdings will then be $115,000, the same as cash.

In the next period, the stock drops to $70. The market value of our equity holdings declines to just $61.9k. while the overall portfolio is now $176.9k (compared to $230k before).

We have to buy more shares this time. To match equity and cash, we buy 379 shares at $70, increasing the value of our stocks to $88.5k.

The process continues each time, rebalancing shares and cash by either selling some shares or buying more of them.

Note that we buy more shares at a lower price without doing any valuation work. We also sell more shares at a higher price, again disregarding P/E or other metrics.

After 20 iterations, the value of our portfolio rises to $475.5k, gaining 138% (2.4x).

So, the beauty here is that a cyclical stock that remains range-bound for a long time can help you achieve 138% total returns.

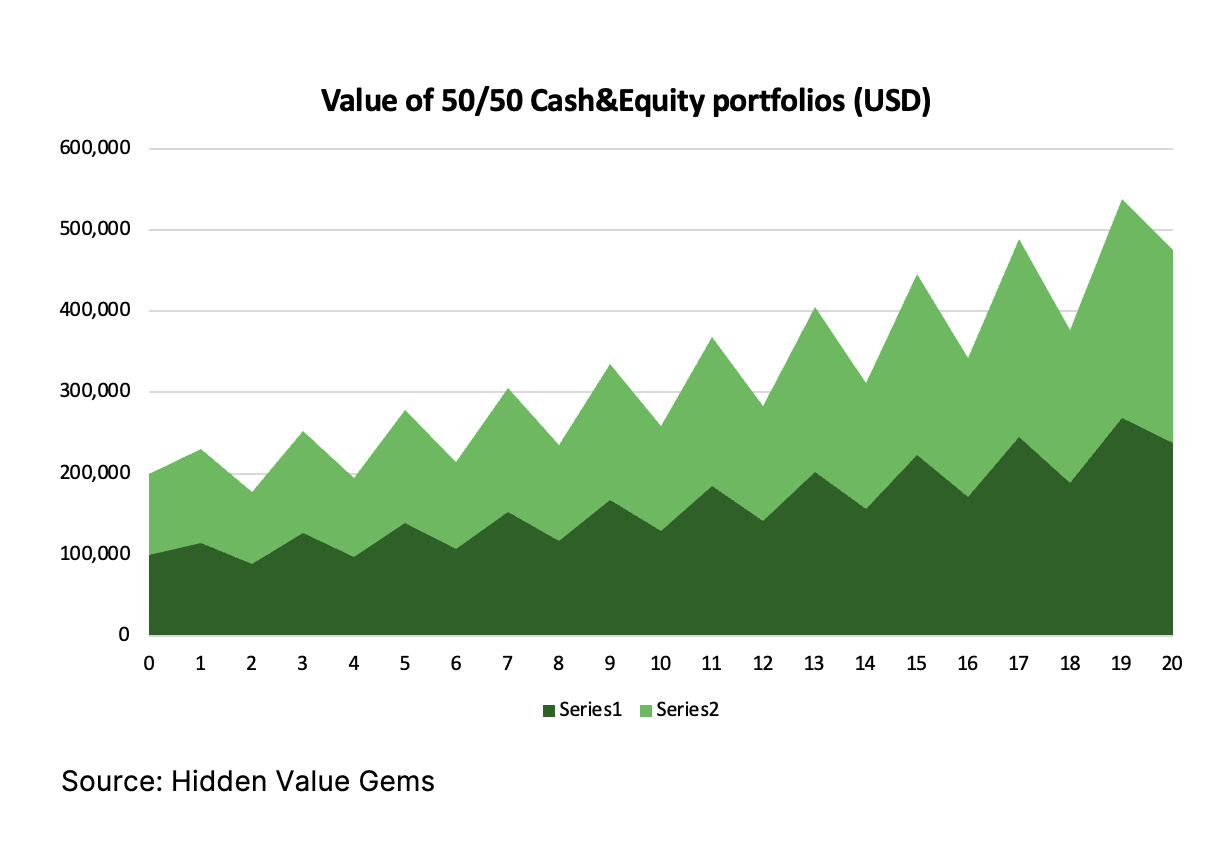

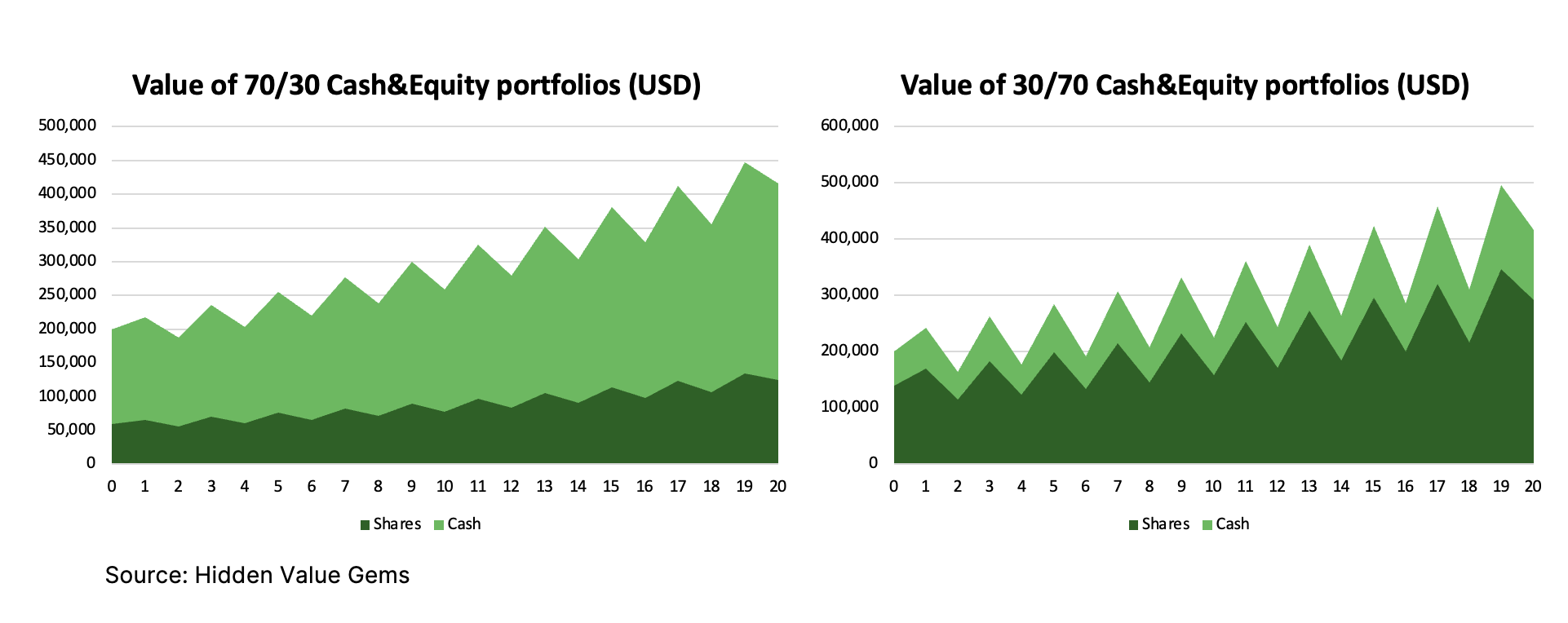

In case you wonder what happens if you follow a 30/70 or 70/30 allocation, here is the chart:

In case you wonder what happens if you follow a 30/70 or 70/30 allocation, here is the chart:

Actionable points

I think there are several points that you can apply in practice from the example above.

- It pays off to build a position in a stock gradually. For example, if you want to hold 10% of your portfolio in Berkshire, it is better to spread your purchases over 3-4 transactions rather than a single one. Every stock is volatile. At a minimum, there are external factors, such as macro and sentiment. Besides, from a probability perspective, you cannot be 100% sure that you picked the bottom for the stock. Hence, you will get the chance to buy the same price at a lower price later.

- If you deal with a cyclical business, periodic rebalancing (once a year, for example) could improve your results.

- Such a strategy doesn’t require special skills. In fact, it can even be executed automatically. A simple rule delivers better results than human judgment.

- Holding some cash is always good as it adds resilience to your portfolio and your life. By the way, Ray Dalio has switched from calling cash “trash” to “cash is now good”. Although his logic is based on the current bonds, stocks and cash yields. So his view may change again in the future.

As you can see, alternative weights decrease the final results. I still like that with a much smaller allocation to shares (30%), you can achieve the same result as with a 70% weight in shares. You can access more liquidity at any time and enjoy much lower volatility of your portfolio, and still more than double your money.

When the system does not work?

No system is perfect, of course. The system will fail if you deal with a secular-growth company or a business in a permanent decline. Imagine you buy Google in 2010 and then sell it a year after. You would have been selling the stock almost every year as it continued to grow all the way to 2023.

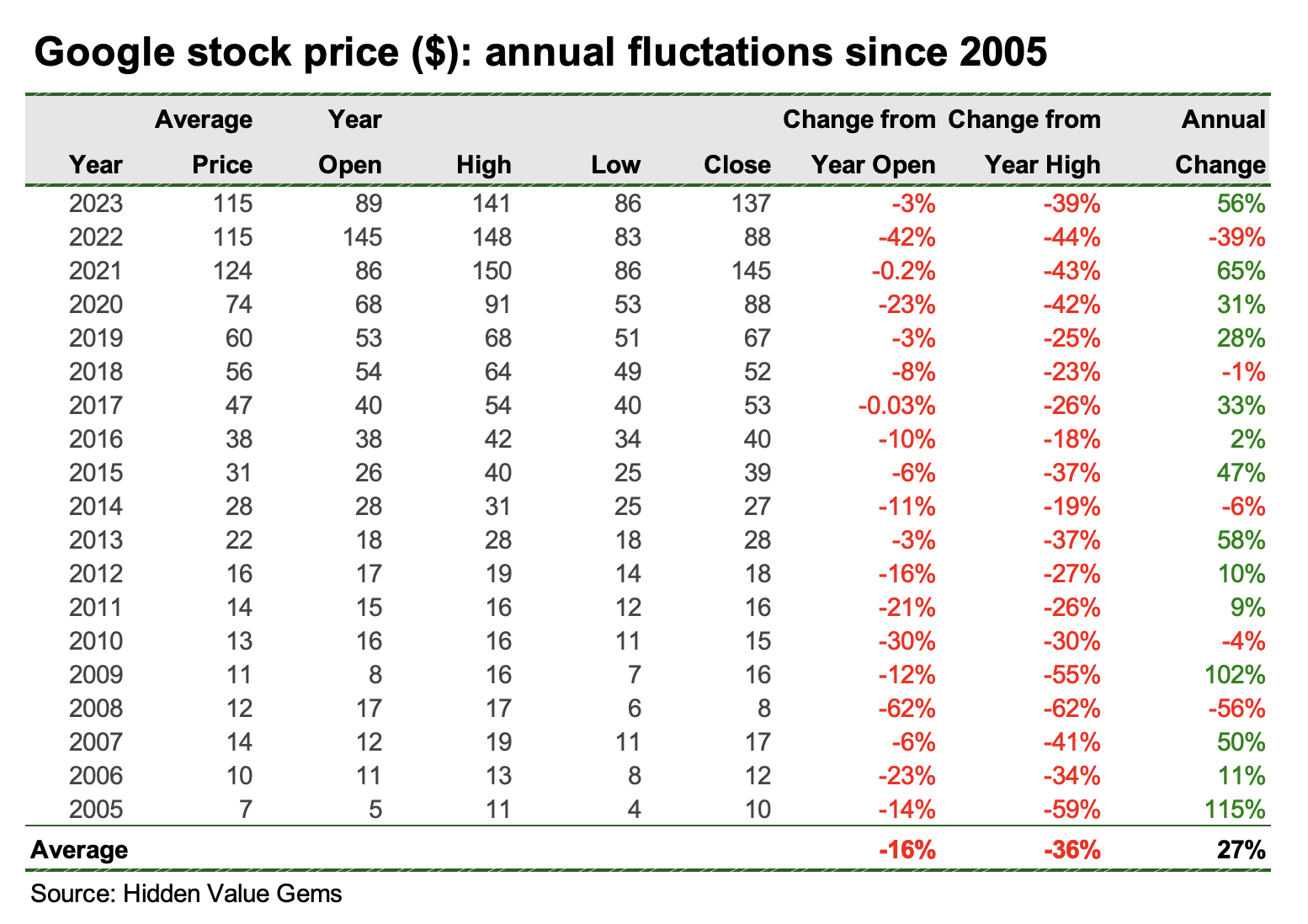

To be honest, the actual results depend on what weight you assign to equities and how often you want to rebalance your portfolio. Before publishing this post, I looked at Google’s price fluctuations throughout the year.

The results are pretty interesting.

Every year since Google went public (2005), its stock traded lower than at the start of the year. The average drop from the start of the year has been -16%. But if we track declines from the highest prices achieved every year, the average drop is already -36%. This is the drop in the same year.

To be honest, the actual results depend on what weight you assign to equities and how often you want to rebalance your portfolio. Before publishing this post, I looked at Google’s price fluctuations throughout the year.

The results are pretty interesting.

Every year since Google went public (2005), its stock traded lower than at the start of the year. The average drop from the start of the year has been -16%. But if we track declines from the highest prices achieved every year, the average drop is already -36%. This is the drop in the same year.

The worst results come from adding to a losing position if a company is in a permanent decline (e.g. Sears), although they will still be better than a simple buy-and-hold strategy.

So, how do we avoid these situations?

First, the companies that continue to grow for decades are a true exception. The probability that a stock you bought turns out to be the next Amazon or Apple is extremely low. There is a higher chance that the company will continue to shrink until it disappears.

To avoid that latter, I cannot think of anything better than focusing on the six key questions:

In an ideal case, the stock drops because of poor macro or sentiment. Yet, with a strong balance sheet, strong operating margins, its operations remain profitable. If the market cap approaches the value of the cash position, then you probably have low downside risks and significant upside potential.

Franklin Templeton, a US-listed asset manager, may be a good example. It is not the best business, but it has been run with a net cash position by the founding family.

So, how do we avoid these situations?

First, the companies that continue to grow for decades are a true exception. The probability that a stock you bought turns out to be the next Amazon or Apple is extremely low. There is a higher chance that the company will continue to shrink until it disappears.

To avoid that latter, I cannot think of anything better than focusing on the six key questions:

- Product: is it a good product that customers really like? Do competitors offer much better or cheaper products?

- Business economics: does the business generate returns above its cost of capital?

- Leverage: any issues paying the interest? What happens if sales drop 10%? Any hidden liabilities, fixed operating costs?

- Management: are they honest, experienced and have ‘skin in the game’?

- Capital allocation: how has the company allocated capital between maintenance of operations, new growth opportunities and returning cash to shareholders?

- Valuation: is the stock expensive? More expensive than peers? What is the required growth rate to justify current valuation multiples?

In an ideal case, the stock drops because of poor macro or sentiment. Yet, with a strong balance sheet, strong operating margins, its operations remain profitable. If the market cap approaches the value of the cash position, then you probably have low downside risks and significant upside potential.

Franklin Templeton, a US-listed asset manager, may be a good example. It is not the best business, but it has been run with a net cash position by the founding family.

In 2020, its stock dropped to $15, which was roughly the same as its market cap. I bought it thinking I had little downside. I sold it in 2021.

Post Scriptum

While I discussed the benefits of regular rebalancing in this post, I do not advocate for regular profit-taking. If you can buy stocks and forget about them for 20 years, you will likely outperform the majority of investors (buying a broad-market ETF is probably even better). However, if you are like me and want to try to add value to the process by proactively searching for new ideas, the strategy I discussed has some merits.

- Firstly, keeping some cash adds resilience.

- Secondly, purchasing a stock through a series of transactions over time (a few months, for example) is also worth considering.

- Thirdly, if a company operates in a cyclical industry (e.g. commodities), reducing your position after a strong run and not being afraid to buy after a big drop (provided that the balance sheet remains solid + other factors mentioned earlier) can also improve your returns. In general, introducing rules that force you to act and reduce your judgment is also something worth considering.

- Other interesting rules to consider include buying not more than 5 new stocks every year (Buffett even said that he could “improve your ultimate financial welfare by giving you a ticket with only 20 slots in it so that you had 20 punches — representing all the investments that you got to make in a lifetime.”)

Thank you for reading this article. If you found it useful, I would appreciate it if you could share it with your friends.