This is why I regularly review my old positions and analyse what went wrong and what mistakes I made. I plan to share my past mistakes on this website - hopefully, this would help me make less of them in the future and might even help others do better in their investment process.

I have discovered over time that selling too early is one of such mistakes. This is what I am going to discuss today. I also recommend a book - The Art of Execution - where selling too early is discussed (You can find my review of that book here).

Back in 2017, I bought Buckle at about $18 as a ‘Turnaround case’. The stock had fallen from over $40 back in 2011-2015 over 50%, was paying a regular annualised dividend of $1 (over 5% yield) + introduced special dividend ($1) partially to optimise its capital structure. It was earning just under $2 per share, so the regular dividend was well covered. The company had no financial debt and about $240mn in surplus cash.

About five years before, the company earned over $3 per share and grew sales by 5% per year. From 2015, sales started to decline at about the same rate. As a result, sales went back to $900mn in 2017 (same level as 2009).

My thesis in summer 2017 was that this was not a permanent decline. I thought the worst case would be that I would earn about 10% in cash returns (regular + special dividend) if management could not figure out how to turn things around. If they did, I could earn additional capital appreciation as earnings start growing again, and PE would expand from about 10x (or 7x excluding cash) to a more reasonable 15x. Possibly a 100% return coming from earnings growth, PE expansion and dividend yield.

The fact that a founder and top management owned 43% of the company gave me additional hope. I also liked the fact that the company’s market cap was under $1bn - too small for many professional (’smart’) investors to even consider this company. It was equally exciting to hear just 3-4 analysts during quarterly earnings calls compared to sometimes 10-20 analysts asking questions on calls organised by blue-chip names.

The problem was that the company’s like-for-like sales continued to decline almost every month and every quarter since I bought the shares. Initially, the stock started to go up to $25-28 by the summer of 2018 as the special dividend was maintained and probably the market was willing to give some benefit of the doubt, but then the stock went down again to $18 in early 2019 and fell further to $15 in summer 2019.

Having been receiving regular negative operating updates and also reading and listening about broader problems in traditional retail (‘death from Amazon’), I started challenging my assumptions. Perhaps, the scale of the problem was much bigger and the future much darker than I thought.

In the end, I sold my position at about the same price I bought it for, earning just over 15% from dividends that I received while holding the stock.

First, I thought it was the right decision as Buckle continued to deliver weak operating results, its stock touched $15 in summer 2019 and almost hit $14 in March 2020, but then things started to turn. By the end of 2020, the company’s sales growth (including on a like-for-like basis) turned positive and reached almost 10%. Management raised both - regular dividend to $1.2 (on an annualised basis) and a special dividend to $2.

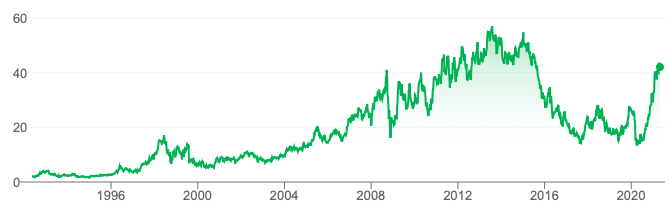

The stock closed at $41.94 on 30 April 2021 - 133% higher (over 170% return if dividends are included).

So my original thesis turned out to be correct, but the actual results were much worse compared to what I could have earned if I stayed with my thesis.

Buckle share price ($)

The straightforward conclusion from this is that I did not have enough patience to stick to my position faced with negative news and opinions of others. However, in a different situation, patience was exactly the reason that led to a 90% loss.

My thesis on the second company (an offshore oil rig company) was that the price was very attractive and reflected an extremely pessimistic view - the replacement cost of the company’s assets was almost 10x higher than the market capitalisation. I also reasoned that continuous reduction in CAPEX across the oil industry would eventually lead to supply issues, pushing the oil price and especially drilling rates higher. So the company which I owned a piece of would eventually be able to earn adequate returns on its capital. I first bought the stock in 2017 but then sold it in early March 2020 with about a 90% loss. The company remains in administration as I write this post.

The second example made me aware that patience can be dangerous if you hold the ‘wrong’ stock or stock in the ‘wrong’ sector.

So the question I started asking myself was this: Is it really lack of patience in the first case and bad luck in the second case (i.e. Pandemic was almost impossible to predict - and that was the final trigger for the oil rig company to go bust)? What if luck played a role in both cases (i.e. how could I know in advance that Buckle would be able to turn things around)? How probable was it for Buckle to go into administration the way many other retailers did in the past five years?

Of course, there are obvious differences between the two cases in hindsight. In the first one, there was a large founding shareholder; the company had a net cash position and attractive margins (gross margins of 40%+, net income margin of over 10%). So even with declining sales, it did not face immediate liquidity problems or financial losses.

The second company was quite leveraged, had high operating leverage (i.e. its earnings were very sensitive to changes in sales), practically no insider ownership and was operating in a much more cyclical / commodity industry. It was a price taker, and there was little it could do about the downturn. Cost-cutting was not sufficient. Management started acquiring competitors to consolidate the sector, but it was a little too late.

So at least in terms of probabilities, I could say that I had more chances in the first case than in the second one.

I added to My Checklist points about Leverage, Ownership structure, Operating leverage and nature of the industry (cyclical or not, barriers to entry, commoditised or with differentiated products). I hope I have learnt some lessons from those mistakes.

But I also think there is one more takeaway from them with three possible solutions.

In his book The Most Important Thing, Howard Marks discusses the concept of taking risks that you cannot observe, which creates an illusion of safety. For example, you need to cross the jungles either by river or the forest. You choose the woods and come out safe, but your friend picks the river and is attacked by a crocodile. Later, you learn that there were 10 lions and 40 snakes in a forest, but you were lucky to pass them, while the only crocodile that usually lives in another part of the river happened to notice your unlucky friend. You picked the riskier route but were lucky despite that.

In one of the first books, Fooled by Randomness, Nassim Taleb discussed a similar concept of luck in various parts of life, which we often confuse with skill (e.g. we try to explain a person’s rise to the role of CEO by his personal qualities and underestimate the role of chance that could have helped him in his career). Since I am on the subject of relevant books, I should also mention Anne Duke’s Thinking in Bets book (should be in my Library quite soon).

So the takeaway is that the method of picking undervalued stocks was correct, but it does not always lead to profitable investments. It is important to differentiate between the technique and its results. Unsatisfactory results from a few stocks do not automatically mean that the overall method is wrong.

Here, I would like to make a clear distinction between two investing methods which I plan to cover in more detail in a separate post. The first one is more focused on the price paid relative to the company’s assets and earnings. The second method is focused more on the business and where it can be in 5-10 years. In the first method, an investor hopes to make money by paying the price lower than the company’s fair value. Returns are earned when the discount (between market price and company’s intrinsic value) ceases to exist as price reaches value.

The idea behind the second method is that in the long-term, stock’s return matches returns of the underlying business (e.g. if a company continues to invest its capital at 30% for 30 years, the stock would generate a return of about 30% p.a. over that period, with little difference between what price you paid initially - 20x PE or 40x PE).

I think it is important to be clear from the beginning which of the two methods you are following. The first method does not focus so much on one individual stock, but rather a group of stocks. The idea is that you stack probabilities in your favour so that over time if you continue following this method you should generate quite attractive returns (10% or more). Patience in holding a single stock is less relevant in this method, what counts is consistency and being able to stay in the game long enough. This means diversification is important, so having more than 5% of your portfolio may be a bit too risky, 20-40 stocks with 2-5% weight could be a reasonable level of diversification.

In the second method, you make a bet on a specific company, so knowing it much better than an average investor and having high conviction in your assumptions about management, product, industry, competitors and customers is crucial.

In both cases that I described I originally followed the first method, but increased the weight of a drilling company to about 10% of my portfolio - as if it was my high-conviction idea in the second method.

So there are three main practical takeaways from my mistakes.

Firstly, make sure you buy only a small position of a company that you do not have a real edge on and especially if it has high debt and it is operating in a cyclical commodity industry. As long as you bet on a systematic approach (on a group of stocks) - just keep following the process, consistency is more important than individual stock selection. But to have the ability to run this process over a long period of time, you need staying power which you could lose if you bet too much on one single stock (using this first method of investing).

My second conclusion is that you need to be convinced that the business is doing well and any headwinds are temporary if you follow the second approach. It takes a lot of time and effort to get an edge in a particular sector or company, so if you invested a lot of your time in this - make sure you have enough of the stock in your portfolio to make these efforts worthwhile. Having at least 10% of your portfolio in a high-conviction idea looks reasonable. Patience is key with such types of companies. For example, shareholders of Netflix endured an 80% drawdown that lasted 16 months in the 2010s, Apple and Amazon shareholders experienced 79% and 91% drawdowns, respectively, that lasted 36 months in the case of Apple and 19 months in Amazon’s case. I cannot find exact data, but I remember seeing such statistics that Netflix stocks spent about 60% of their time trading below its all-time high suggesting that in the short-term there were higher chances of you losing money in Netflix at any point right after you bought its shares. According to professor Bessembinder, the 100 most successful companies in terms of shareholder wealth creation were associated with an average drawdown of 51.6% during the prior decade.

And finally, my third conclusion is that it helps to change the weight of your position depending on new information (specifically, developments in the sector and the company). If you put just 5% of your capital into a company that you think you understand very well and see prospects for 20-30% returns on capital over many years ahead, make sure you add to your position as long as you get more confirmation of company’s strengths and even more important when you get evidence that your original concerns and perceived risks are not valid.

This also suggests that it could also be helpful to reduce your position gradually, in stages, rather than immediately. If you bought a strong business but over time nothing gives you confidence that this is an exceptional business capable of growing at 20-30%, while the stock goes up 50% a year for three years in a row, you may sell part of your position (20-30%) initially.

To conclude, avoiding the mistake of selling too soon, consider 1) investing only a small share of your portfolio in a stock initially (so you can hold through long enough); 2) make sure you have a deep understanding of the business which should give you more confidence to stick to your position; 3) exit your positions gradually, selling in parts over time.

Did you find this article useful? If you want to read my next article right when it comes out, please subscribe to my email list.