6 April 2025

HVG portfolio has outperformed broad indices

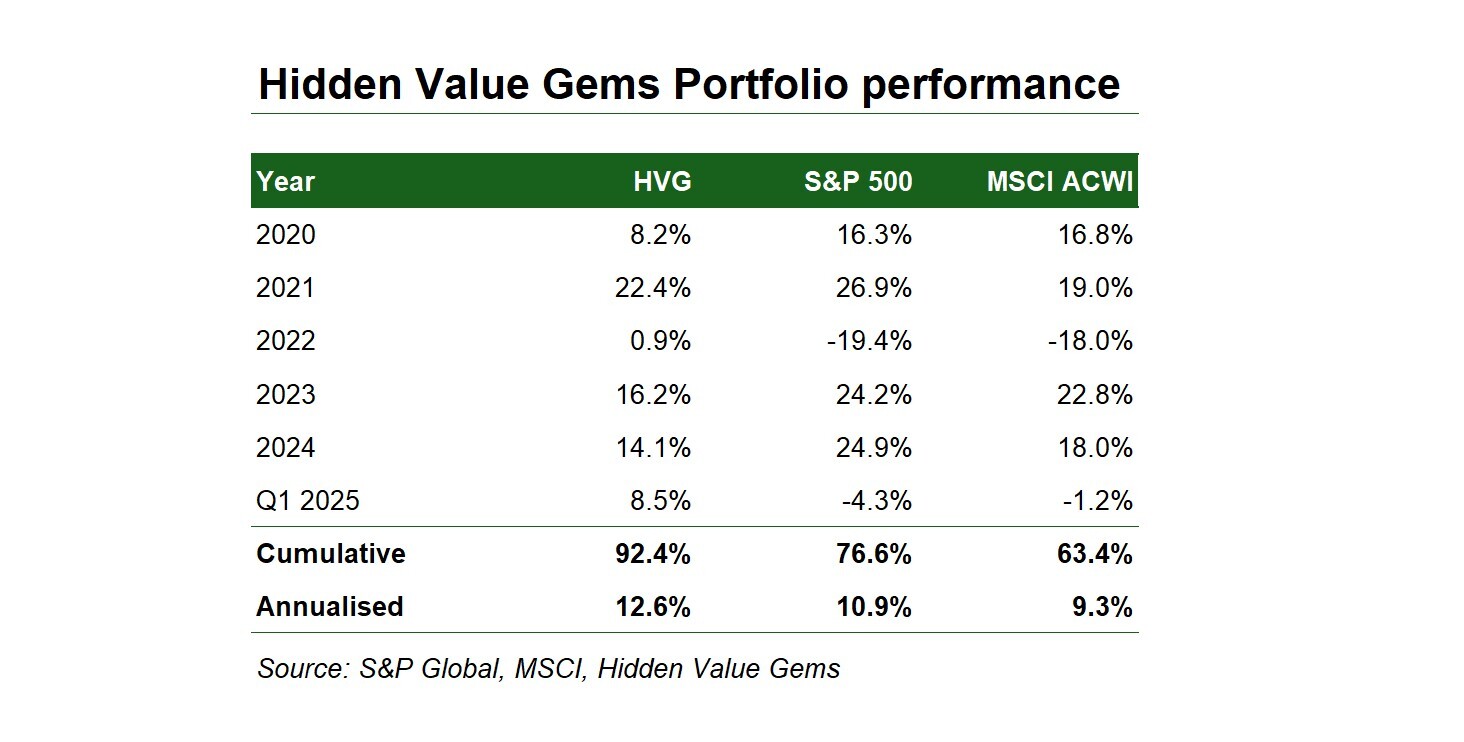

The HVG portfolio delivered a 8.5% total return in Q1 2025, significantly outperforming both the S&P 500 (-4.3%) and MSCI World ex-US (-1.2%).

Long-time readers may be familiar with the more defensive approach of the HVG portfolio, which tends to do better during weaker market conditions. Our preference for capital allocators, insurance, international stocks, and above-average cash position contributed to the outperformance.

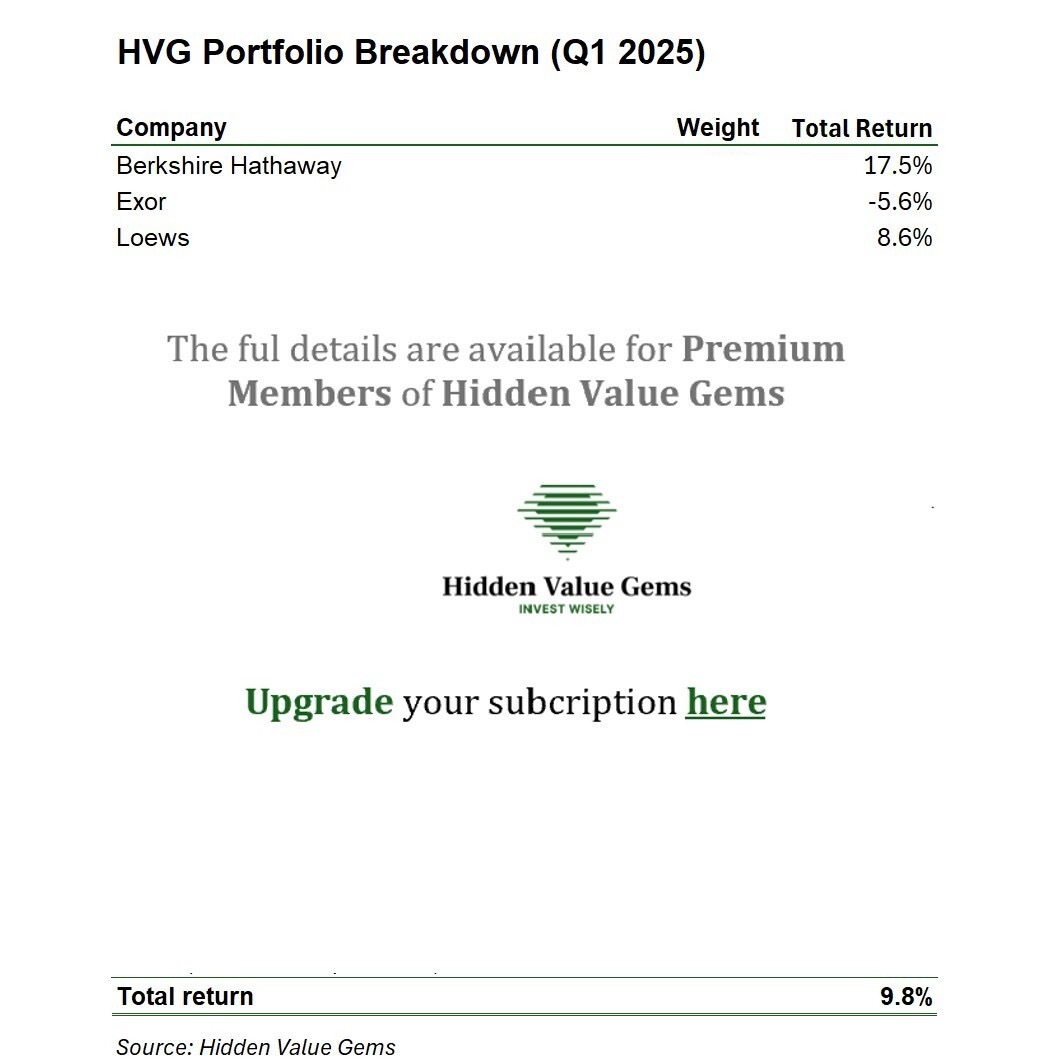

Here are the HVG portfolio positions with Q1 performance and weights.

Here are the HVG portfolio positions with Q1 performance and weights.

What to do now

The magnitude of the tariff changes introduced by the new US administration is staggering. The worrying issue is that the changes seem to be based on deep conviction that the US is ‘exploited’ by its trading partners and the need to ‘rebalance’ global trade.

The scale of potential changes reminds me of 2020 and even 2008. The good news is that markets recovered from both crises reasonably quickly. But it was quite painful for a few months. Leveraged investors could not survive, failing just like some businesses (e.g. Lehman Brothers).

I am sure this is what most investors are asking themselves today:

Of course, a lot depends on your circumstances and temperament. I thought tapping into the insights of some of the greatest investors could provide some ideas of what one can do today. I will briefly share my strategy at the end.

The scale of potential changes reminds me of 2020 and even 2008. The good news is that markets recovered from both crises reasonably quickly. But it was quite painful for a few months. Leveraged investors could not survive, failing just like some businesses (e.g. Lehman Brothers).

I am sure this is what most investors are asking themselves today:

- Should I reduce my equity exposure to avoid further losses and have dry powder to buy stocks cheaper?

- Should I switch between stocks (e.g. sell Growth companies, buy more Value)?

- Is there a case for adding other asset classes (e.g. bonds and commodities/gold)?

- Is ‘sitting tight’ and doing nothing the right course of action?

Of course, a lot depends on your circumstances and temperament. I thought tapping into the insights of some of the greatest investors could provide some ideas of what one can do today. I will briefly share my strategy at the end.

Learning from the Greats

Stanley Druckenmiller

Perhaps the best macro trader, Druckenmiller’s core strength is his ability to instantly change his opinions when he learns new facts or markets present different opportunities. The common perception is that he analyses the global macro picture and then makes several concentrated bets which deliver outstanding returns. I think the reality is slightly different. He may deliver mediocre or negative returns for most of the year until he stumbles on one or two exceptional opportunities that make up for the losses and provide all the performance.

Speed and concentration when the opportunity presents itself are crucial for this approach. In hindsight, most of the great trades looked easy and obvious, but few people executed them because it was much harder in real-time.

I personally know successful investors who shorted the S&P 500 back in February 2020 on the premise that COVID was a serious issue (based on evidence from China, Italy, and other countries). Yet the market had just made an all-time high and was trading at a reach valuation multiple.

Some were also shorting oil.

I am sure they have a few shorts today, as the downside to most stocks seems more significant than the upside.

One of the key skills required in this approach is to change the view quickly. As Druckenmiller often once said, ‘Successful investing requires strong opinions, lightly held”. It is actually much harder than it appears.

His story about the challenges of investing during the Tech bubble is quite telling: He first shorted some Internet stocks, then went long almost at the market top. Finally realising his mistakes, he pivoted and ended the year making over 40% returns.

Here is a short version of this story and a long one.

Speed and concentration when the opportunity presents itself are crucial for this approach. In hindsight, most of the great trades looked easy and obvious, but few people executed them because it was much harder in real-time.

I personally know successful investors who shorted the S&P 500 back in February 2020 on the premise that COVID was a serious issue (based on evidence from China, Italy, and other countries). Yet the market had just made an all-time high and was trading at a reach valuation multiple.

Some were also shorting oil.

I am sure they have a few shorts today, as the downside to most stocks seems more significant than the upside.

One of the key skills required in this approach is to change the view quickly. As Druckenmiller often once said, ‘Successful investing requires strong opinions, lightly held”. It is actually much harder than it appears.

His story about the challenges of investing during the Tech bubble is quite telling: He first shorted some Internet stocks, then went long almost at the market top. Finally realising his mistakes, he pivoted and ended the year making over 40% returns.

Here is a short version of this story and a long one.

Peter Lynch

Peter Lynch is another investment legend with a completely different approach. While he was predominantly a stock picker, he navigated his portfolio during various economic conditions by rebalancing different stock types.

So, for example, he categorised stocks into groups like stalwarts, cyclicals, fast and slow growers, turnarounds/asset plays, each suited to different phases of the economic cycle. The weight of each group of stocks at any point depended on a mix of macro indicators and relative performance.

For example, if, following an extended period of outperformance, the valuation of growth stocks became stretched, he would trim those positions and increase the weight of stalwarts and slow growers as their weight dropped following a period of underperformance.

The benefit of this approach is that his portfolio remained fully invested at all times. Lynch did not take explicit market views on when to sell stocks and go into cash and when was the bottom to re-enter the market.

While not directly timing the market, Lynch managed to indirectly position its portfolio depending on the market phase.

Personally, I met several investors who were deliberately buying non-discretionary companies like Nestle at the start of the year as they saw them undervalued and a good hedge against potential market drop.

So, for example, he categorised stocks into groups like stalwarts, cyclicals, fast and slow growers, turnarounds/asset plays, each suited to different phases of the economic cycle. The weight of each group of stocks at any point depended on a mix of macro indicators and relative performance.

For example, if, following an extended period of outperformance, the valuation of growth stocks became stretched, he would trim those positions and increase the weight of stalwarts and slow growers as their weight dropped following a period of underperformance.

The benefit of this approach is that his portfolio remained fully invested at all times. Lynch did not take explicit market views on when to sell stocks and go into cash and when was the bottom to re-enter the market.

While not directly timing the market, Lynch managed to indirectly position its portfolio depending on the market phase.

Personally, I met several investors who were deliberately buying non-discretionary companies like Nestle at the start of the year as they saw them undervalued and a good hedge against potential market drop.

Claude Shannon

While hardly an investment legend, Claude Channon is often viewed as the father of the Information Theory. Yet, in a wonderful and little-known book on Uncertainty and Risk (The Fortune’s Formula), William Poundstone described how Channon proposed a strategy that generated positive gains from a randomly changing stock without a clear direction.

Here is how Channon’s strategy (also known as Channon’s Demon) works:

By following Shannon’s strategy, the investor can turn market’s wild swings into his favour. By sticking to a disciplined strategy - keeping a set amount in cash and regularly rebalancing - you’re effectively buying the dips and selling during the spikes, which can add up to positive returns over time even if the market seems directionless.

And the really cool part is the math behind it: even if a stock is just bouncing around randomly, those ups and downs create opportunities. When you rebalance, you're capturing the "free lunch" that volatility offers (buying low and selling high) - turning what looks like unpredictable chaos into a consistent edge.

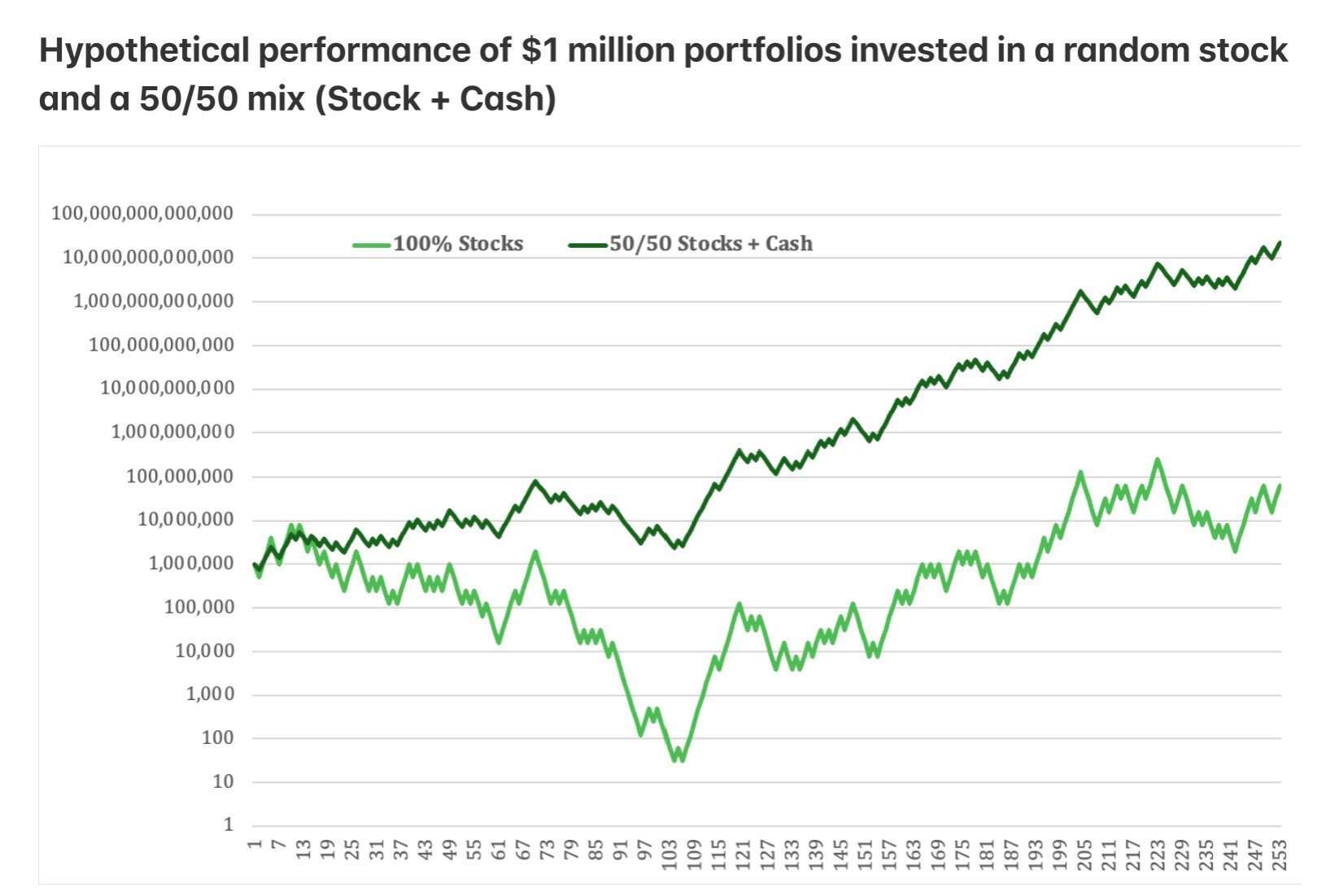

I have reconstructed a hypothetical performance of such a portfolio in Excel. Here is

Here is how Channon’s strategy (also known as Channon’s Demon) works:

- Constant Weight Allocation: The investor splits his portfolio into cash and a random stock equally. He then maintains equal weight between the two assets.

- Rebalancing Mechanism: As the stock price fluctuates, the allocation naturally deviates from the predetermined weights. If the stock rises, its share in the portfolio increases; if it falls, its share decreases. The investor then rebalances—selling a portion when the stock is high and buying more when it is low—to return to the original allocation.

- Harvesting Volatility: This periodic rebalancing creates a “buy low, sell high” effect. Even if the stock's average return over time is zero (i.e., it moves randomly without a clear trend), the systematic rebalancing can generate positive returns. The rebalancing profit comes from the volatility rather than any directional movement of the stock.

By following Shannon’s strategy, the investor can turn market’s wild swings into his favour. By sticking to a disciplined strategy - keeping a set amount in cash and regularly rebalancing - you’re effectively buying the dips and selling during the spikes, which can add up to positive returns over time even if the market seems directionless.

And the really cool part is the math behind it: even if a stock is just bouncing around randomly, those ups and downs create opportunities. When you rebalance, you're capturing the "free lunch" that volatility offers (buying low and selling high) - turning what looks like unpredictable chaos into a consistent edge.

I have reconstructed a hypothetical performance of such a portfolio in Excel. Here is

Source: Hidden Value Gems

Applying this concept to today’s market, one would have been selling strongly performing equities last year and reversing this year as the share of equities dropped.

Young Warren Buffett

Warren Buffett, who needs no introduction, has two distinct periods in his investment career. In his early years, when he operated with a small amount of money and in more recent decades, when his company, Berkshire Hathaway, exceeded $1 trillion in total assets.

In very simple terms, the young Warren Buffett was all about balance sheets, income statements and special situations (work-outs). With much less information readily available in the 1950s and 1960s, his relentless search for undervalued companies trading at single P/Es and with extraordinary cash positions generated superb results.

To the frustration of many value investors today, he keeps repeating that he could make a ’50% a year on $1 million’ today.

More recently, he talked about arbitrage and market inefficiencies in less-covered stocks that few investors know of.

Given the recent sharp sell-off, more inefficiencies should arise in the market, which is good news for value investors.

In very simple terms, the young Warren Buffett was all about balance sheets, income statements and special situations (work-outs). With much less information readily available in the 1950s and 1960s, his relentless search for undervalued companies trading at single P/Es and with extraordinary cash positions generated superb results.

To the frustration of many value investors today, he keeps repeating that he could make a ’50% a year on $1 million’ today.

More recently, he talked about arbitrage and market inefficiencies in less-covered stocks that few investors know of.

Given the recent sharp sell-off, more inefficiencies should arise in the market, which is good news for value investors.

Warren Buffett Today

Buffett looked out of sync throughout 2024 when he was a net seller of stocks, notably cutting Berkshire’s Apple investment in half while the stock continued to rally.

Berkshire Hathaway seems to be ideally positioned to face today’s markets as the company was following a price discipline and avoided buying expensive stocks.

It is pretty hard to remain disciplined as bull markets often last longer than anyone expects, but if one adheres to this strategy of not buying stocks when they seem expensive and keeps a higher portion of assets in cash, the current sell-off would be a welcome development rather than a crisis.

In fact, the same price discipline looked like an act of genius back in 1969 when he closed his Partnership and kept a higher-than-usual amount of cash as he patiently waited for better opportunities.

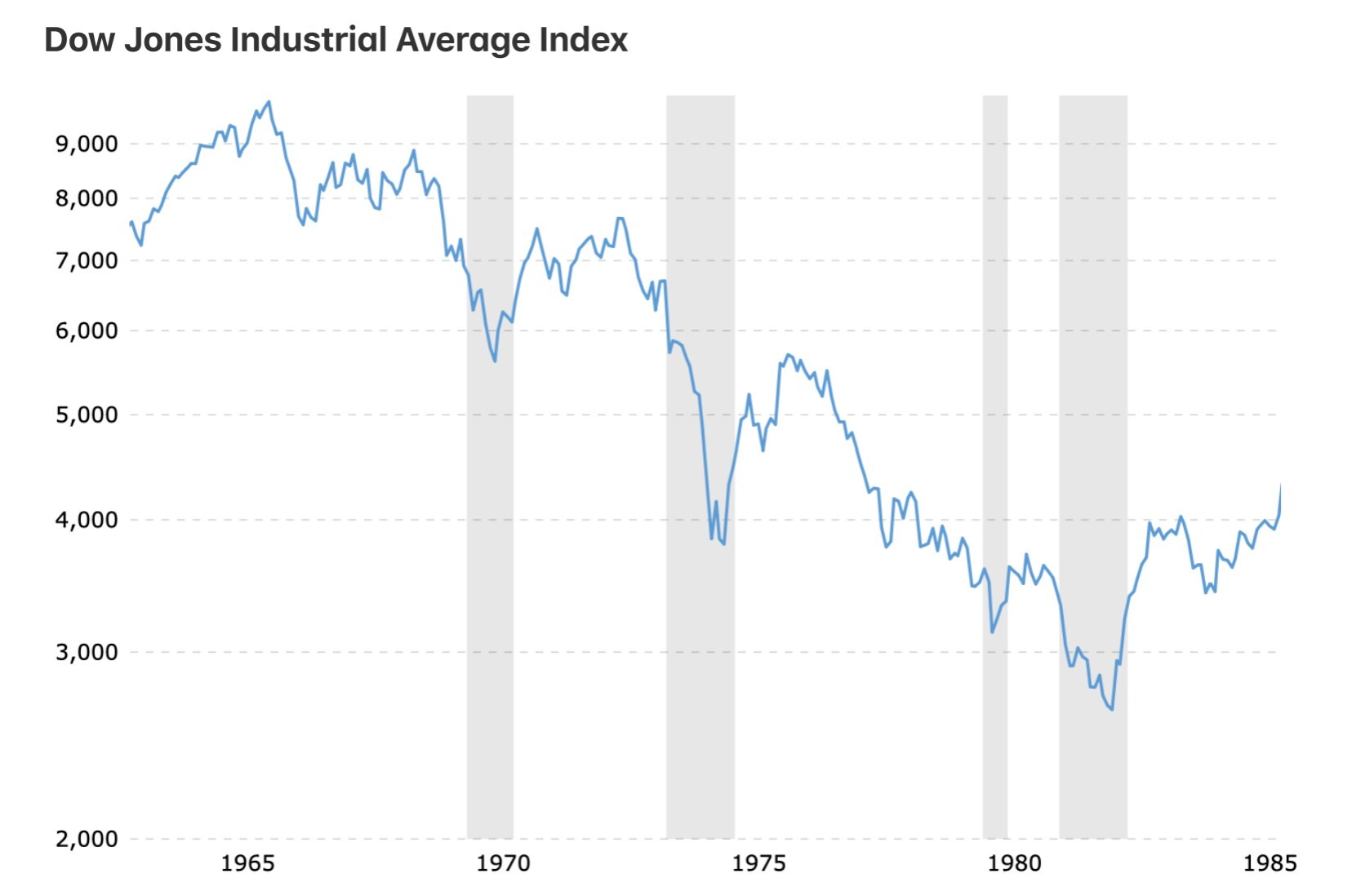

Here is how Dow Jones performed between the 1960s and 1970s when Buffett went on a ‘buyer’s strike’.

Berkshire Hathaway seems to be ideally positioned to face today’s markets as the company was following a price discipline and avoided buying expensive stocks.

It is pretty hard to remain disciplined as bull markets often last longer than anyone expects, but if one adheres to this strategy of not buying stocks when they seem expensive and keeps a higher portion of assets in cash, the current sell-off would be a welcome development rather than a crisis.

In fact, the same price discipline looked like an act of genius back in 1969 when he closed his Partnership and kept a higher-than-usual amount of cash as he patiently waited for better opportunities.

Here is how Dow Jones performed between the 1960s and 1970s when Buffett went on a ‘buyer’s strike’.

Source: Macro Trends

Ben Graham

Ben Graham, the father of Value Investing, introduced the concept of 'net-nets', encouraging investors to focus on margins of safety and pay extra attention to the prices they pay when they buy businesses.

However, he has also paid quite considerable attention to the general market conditions. In later editions of The Intelligent Investor, he discussed market valuations and some outlook for investment returns.

In my earlier reviews of his book, I summarised some of Graham’s strategies and typical investor mistakes. Surprisingly, too many of his comments are very relevant today.

However, he has also paid quite considerable attention to the general market conditions. In later editions of The Intelligent Investor, he discussed market valuations and some outlook for investment returns.

In my earlier reviews of his book, I summarised some of Graham’s strategies and typical investor mistakes. Surprisingly, too many of his comments are very relevant today.

John Templeton

Another investment legend, John Templeton had a unique approach to market timing by rotating his portfolio across global markets driven by valuation and a contrarian approach of buying at a point of maximum pessimism. For example, he started allocating personal capital to Japan in the 1950s and began investing clients’ capital in the country in the 1960s. By 1970, approximately 60% of his portfolio was composed of Japanese equities. He was selling most of the US stocks simultaneously, which looked like a perfect market call as US stocks peaked in the 1960s and went through a protracted decline during the 1970s.

However, as Japanese stocks became more popular and valuations increased in the 1970s, Templeton began reducing his exposure to them. He shifted focus back to U.S. stocks, which were at historical lows during that period.

In essence, Templeton’s genius was his disciplined global perspective — always guided by value, never by popular sentiment. He embraced uncertainty, confident that careful analysis and courage to stand apart would yield superior returns in the long run.

However, as Japanese stocks became more popular and valuations increased in the 1970s, Templeton began reducing his exposure to them. He shifted focus back to U.S. stocks, which were at historical lows during that period.

In essence, Templeton’s genius was his disciplined global perspective — always guided by value, never by popular sentiment. He embraced uncertainty, confident that careful analysis and courage to stand apart would yield superior returns in the long run.

Peter Cundill

Peter Cundill embodied the true spirit of a global value investor, guided by his fundamental principle that "there is always something to do." Even when markets seemed bleak and pessimism dominated, Cundill calmly hunted for undervalued opportunities, confident that bargains could always be found — often in overlooked regions or unpopular sectors.

For instance, during the deep market downturn of the early 1980s, Cundill took bold positions in distressed Latin American debt, recognising exceptional value where others saw only risk. In the late 1980s, he invested aggressively in Swedish equities after their sharp collapse, accurately judging the market's pessimism as temporary. Similarly, amid Japan’s economic slump of the 1990s, he patiently acquired deeply discounted stocks, anticipating an eventual recovery.

Cundill’s disciplined, global approach — always seeking undervalued assets — enabled him to consistently profit from challenging market conditions, demonstrating that even in the toughest markets, there truly is always something to do.

For instance, during the deep market downturn of the early 1980s, Cundill took bold positions in distressed Latin American debt, recognising exceptional value where others saw only risk. In the late 1980s, he invested aggressively in Swedish equities after their sharp collapse, accurately judging the market's pessimism as temporary. Similarly, amid Japan’s economic slump of the 1990s, he patiently acquired deeply discounted stocks, anticipating an eventual recovery.

Cundill’s disciplined, global approach — always seeking undervalued assets — enabled him to consistently profit from challenging market conditions, demonstrating that even in the toughest markets, there truly is always something to do.

HVG Strategy Today

Out of many lessons I have learned over the years, two are particularly relevant today.

1. You earn higher returns over the long term by minimising losses than maximising upside. A portfolio that generates 40% in Year 1 and again in Year 2 but loses 50% in Year 3 may look good with an average return of 10%, but in reality, it would be loss-making after three years (-2%).

2. The best investments are made during crises when valuations are depressed and the economy is at the bottom of its cycle. The challenge, however, is to have dry powder to exploit these opportunities. Simply sitting in cash for 5-10 years waiting for a crisis has too high opportunity costs.

I am not good at making macro forecasts. Sometimes, I am right, but many times I am wrong. Instead, I try to implement macro forecasts indirectly into my portfolio or make it more immune to macro stress.

For example, following the two points above, I have aimed to always hold some cash to take advantage of market volatility and as a hedge against unpredictable market moves. I don’t need to predict the next market crash, but when it comes - the 8-10% cash position suddenly is worth a lot.

Secondly, I hold several companies with strong capital allocation skills, where I can benefit from the expertise of other managers (e.g., Berkshire Hathaway, Exor, Loews). They have the resources to take advantage of market volatility. I can outsource part of my portfolio to well-known allocators.

Thirdly, I own a few insurance companies that are not correlated to the general macro environment. People and businesses buy insurance policies regardless of the economic cycle.

Fourth, I use Five Criteria when searching for new investments, focusing on Business Quality and Strong Balance Sheets. Companies with a net cash position, strong profit margins, and sought-after products usually benefit from crises by expanding their market share even if their share prices drop temporarily.

1. You earn higher returns over the long term by minimising losses than maximising upside. A portfolio that generates 40% in Year 1 and again in Year 2 but loses 50% in Year 3 may look good with an average return of 10%, but in reality, it would be loss-making after three years (-2%).

2. The best investments are made during crises when valuations are depressed and the economy is at the bottom of its cycle. The challenge, however, is to have dry powder to exploit these opportunities. Simply sitting in cash for 5-10 years waiting for a crisis has too high opportunity costs.

I am not good at making macro forecasts. Sometimes, I am right, but many times I am wrong. Instead, I try to implement macro forecasts indirectly into my portfolio or make it more immune to macro stress.

For example, following the two points above, I have aimed to always hold some cash to take advantage of market volatility and as a hedge against unpredictable market moves. I don’t need to predict the next market crash, but when it comes - the 8-10% cash position suddenly is worth a lot.

Secondly, I hold several companies with strong capital allocation skills, where I can benefit from the expertise of other managers (e.g., Berkshire Hathaway, Exor, Loews). They have the resources to take advantage of market volatility. I can outsource part of my portfolio to well-known allocators.

Thirdly, I own a few insurance companies that are not correlated to the general macro environment. People and businesses buy insurance policies regardless of the economic cycle.

Fourth, I use Five Criteria when searching for new investments, focusing on Business Quality and Strong Balance Sheets. Companies with a net cash position, strong profit margins, and sought-after products usually benefit from crises by expanding their market share even if their share prices drop temporarily.

Where does this leave me?

I think I will be reducing my cash position in the next few weeks and months depending on how fast stocks drop and what new economic decisions the US and other countries make in the future.

I may use some of the better-performing stocks, like Berkshire and Loews, to buy smaller companies with more significant upside, but I am not in a rush to do so right now.

I expect most of my positions to continue declining in the near term, but I do not plan to materially cut any of them as it is a little late. Re-entering may be harder as the market bottom is always known post-factum.

You may find my 2021 post also interesting:

I may use some of the better-performing stocks, like Berkshire and Loews, to buy smaller companies with more significant upside, but I am not in a rush to do so right now.

I expect most of my positions to continue declining in the near term, but I do not plan to materially cut any of them as it is a little late. Re-entering may be harder as the market bottom is always known post-factum.

You may find my 2021 post also interesting: