24 March 2024

As some of you already know, I attended the Value Spain conference two weeks ago. It is always inspiring to meet like-minded investors, not to mention 20+ weather and lots of sun in Madrid. I also had very interesting meetings with top management of some owner-operator companies. I even bought a stock of one of the companies I met, CTT (I summarised my thesis for the Premium Subscribers here.

Among many smart fund managers pitching their ideas, there was one with the longest track record and quite impressive performance - Francois Rochon, the founder of Giverny Capital. He spoke previously at various events and podcasts, but I still thought his lessons were worth sharing, not least because of his track record and because they are quite similar to my own strategy, which I share in this newsletter.

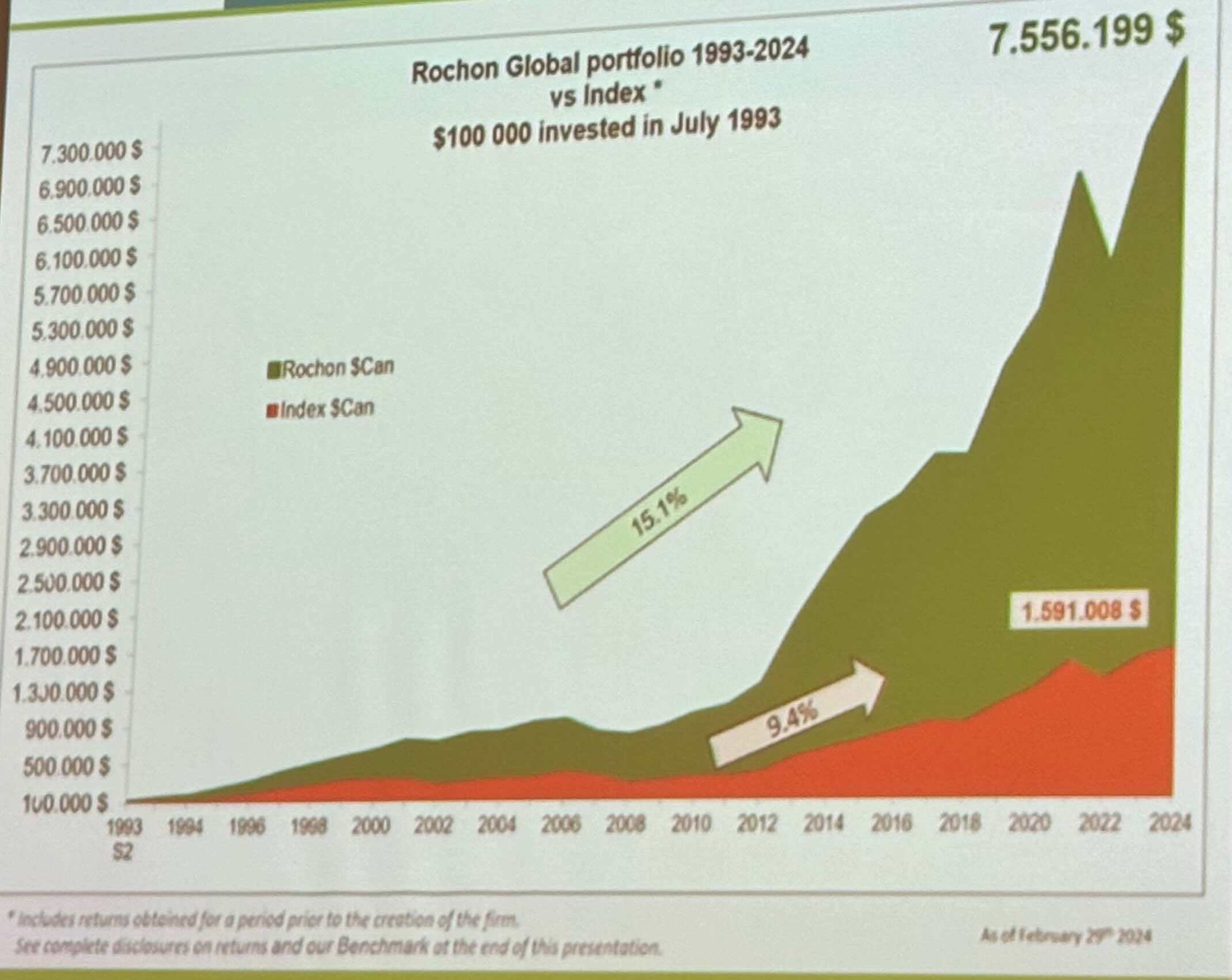

If you invested $100,000 in Francois Rochon's portfolio in July 1993, your investment would be worth $7,556,199 by the end of 2023. This impressive 75.6x growth translates into just 15.1% growth per year. A great example of the power of compounding and investing over the long term.

Among many smart fund managers pitching their ideas, there was one with the longest track record and quite impressive performance - Francois Rochon, the founder of Giverny Capital. He spoke previously at various events and podcasts, but I still thought his lessons were worth sharing, not least because of his track record and because they are quite similar to my own strategy, which I share in this newsletter.

If you invested $100,000 in Francois Rochon's portfolio in July 1993, your investment would be worth $7,556,199 by the end of 2023. This impressive 75.6x growth translates into just 15.1% growth per year. A great example of the power of compounding and investing over the long term.

You probably noticed that this performance is actually in Canadian dollars, but the exchange rate against the US dollar has practically remained the same (1.28 vs 1.36), so there was no impact from FX.

Five ways to underperform the market

Francois first used Munger’s method of inversion by highlighting how investors can underperform the market:

- Invest with the same time horizon as other investors (holding period less than a year)

- Own lots of companies so you don’t differ too much from the average

- Be certain not to be left out of the current fashion/fad/trend (crowd following)

- Believe that you are ‘smarter’ than others and can predict the stock market

- Keep some level of cash (that inevitably will underperform equities)

Five ways to outperform

- To be able to think differently from the others: look at stocks as businesses

- To avoid market predictions: act like an owner

- To own a few carefully selected companies

- To be impervious to market fluctuations: to have an undeterred long-term horizon

- To develop the right behaviours (rationality, humility and patience)

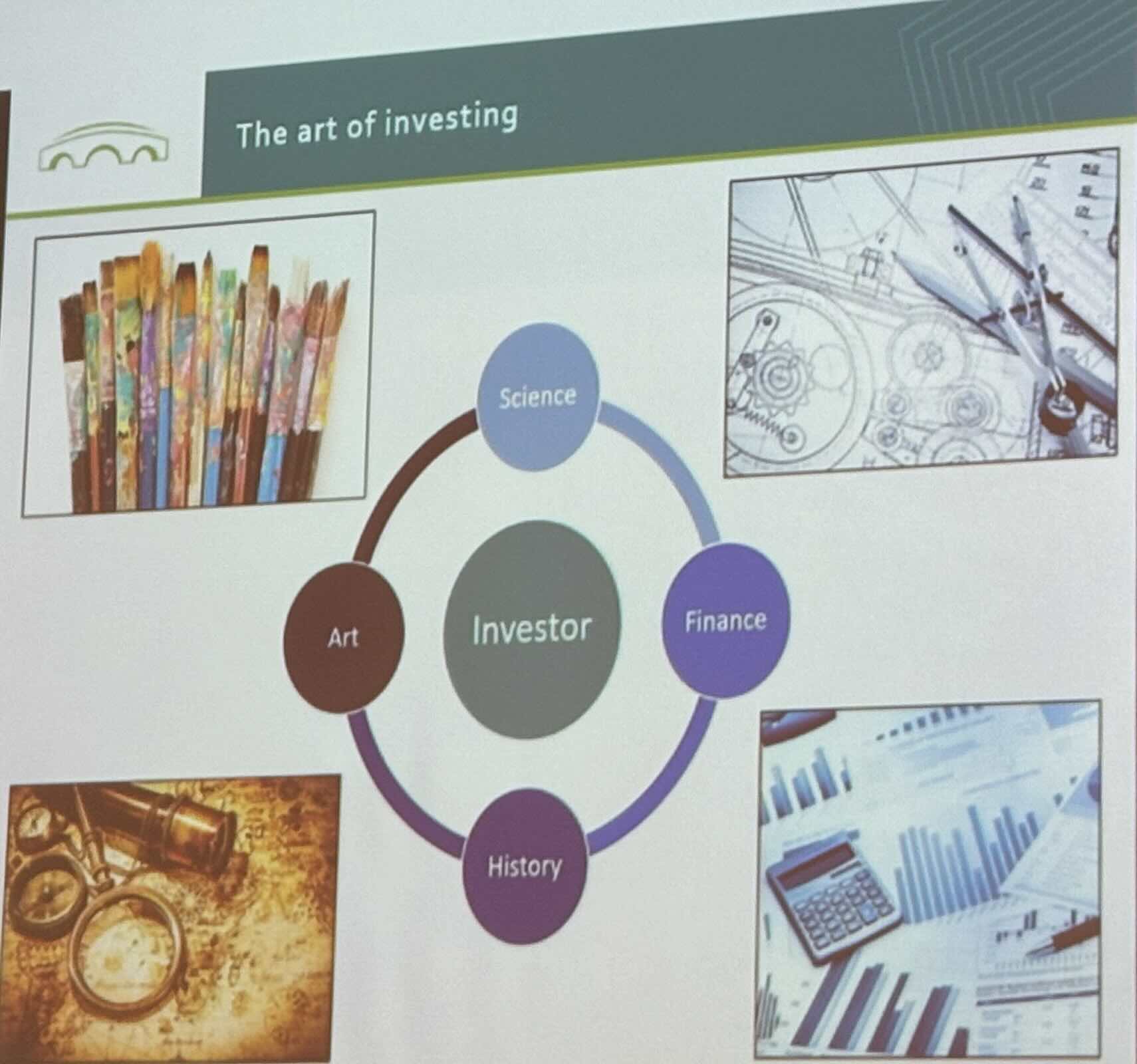

Investing: science, finance, history, and art

Francois then highlighted that investing lies at the intersection of the four different areas: Science, Finance, History and Art.

The last point is very important. To borrow from Francois, “Investing is about being imprecise and accepting to be wrong as often as 30-40% of the time”. Unlike in science, humans “do not behave like atoms”.

- Science is understanding the business and its product, collecting facts.

- Finance is understanding the financial performance of the business (how much it earns and how much capital it consumes).

- History (if I understood correctly) is understanding the evolution of the business and how similar businesses performed in the past.

- Finally, art is dealing with imprecise information and trusting your intuition about business qualities and management.

The last point is very important. To borrow from Francois, “Investing is about being imprecise and accepting to be wrong as often as 30-40% of the time”. Unlike in science, humans “do not behave like atoms”.

Francois Rochon’s Investment Process

I. Idea Generation

II. Quantitative Analysis

III. Qualitative Analysis

IV. Valuation

I thought the last point on valuation was quite interesting. It sounds simple, but it is not something many investors or analysts do. Rather than analyse how much you are paying for this year’s earnings, consider instead what the business could look like in five years and how much it could be worth.

Of course, you can only do this if you are dealing with a quality business outside of cyclical sectors or operating with high leverage. Those companies do not have high longevity or visibility.

Rochon also spoke about the behavioural edge, which had three pillars: Rationality. Humility and Patience.

Rationality is basically keeping a cool head during crashes and manias. There are many charts similar to the following one, but it sill amazes me how often markets go down and how much they ultimate go up in the longer term.

- Large watchlist of companies followed over many years

- Regular contact with a network of industry sources

- Multi-pronged approach using conference, screens, scuttlebutt

II. Quantitative Analysis

- High return on capital

- Significant free cash flow

- Avoidance of excessive leverage

III. Qualitative Analysis

- Business model: Unique assets, barriers to entry, brand awareness

- Management Team: Manager owner, value-creating capital allocation

- Inclusion of ESG consideration at the valuation phase

IV. Valuation

- 5-year valuation model

- Stock purchased at half its estimated value in 5 years (translates into c. 15% annualised return)

I thought the last point on valuation was quite interesting. It sounds simple, but it is not something many investors or analysts do. Rather than analyse how much you are paying for this year’s earnings, consider instead what the business could look like in five years and how much it could be worth.

Of course, you can only do this if you are dealing with a quality business outside of cyclical sectors or operating with high leverage. Those companies do not have high longevity or visibility.

Rochon also spoke about the behavioural edge, which had three pillars: Rationality. Humility and Patience.

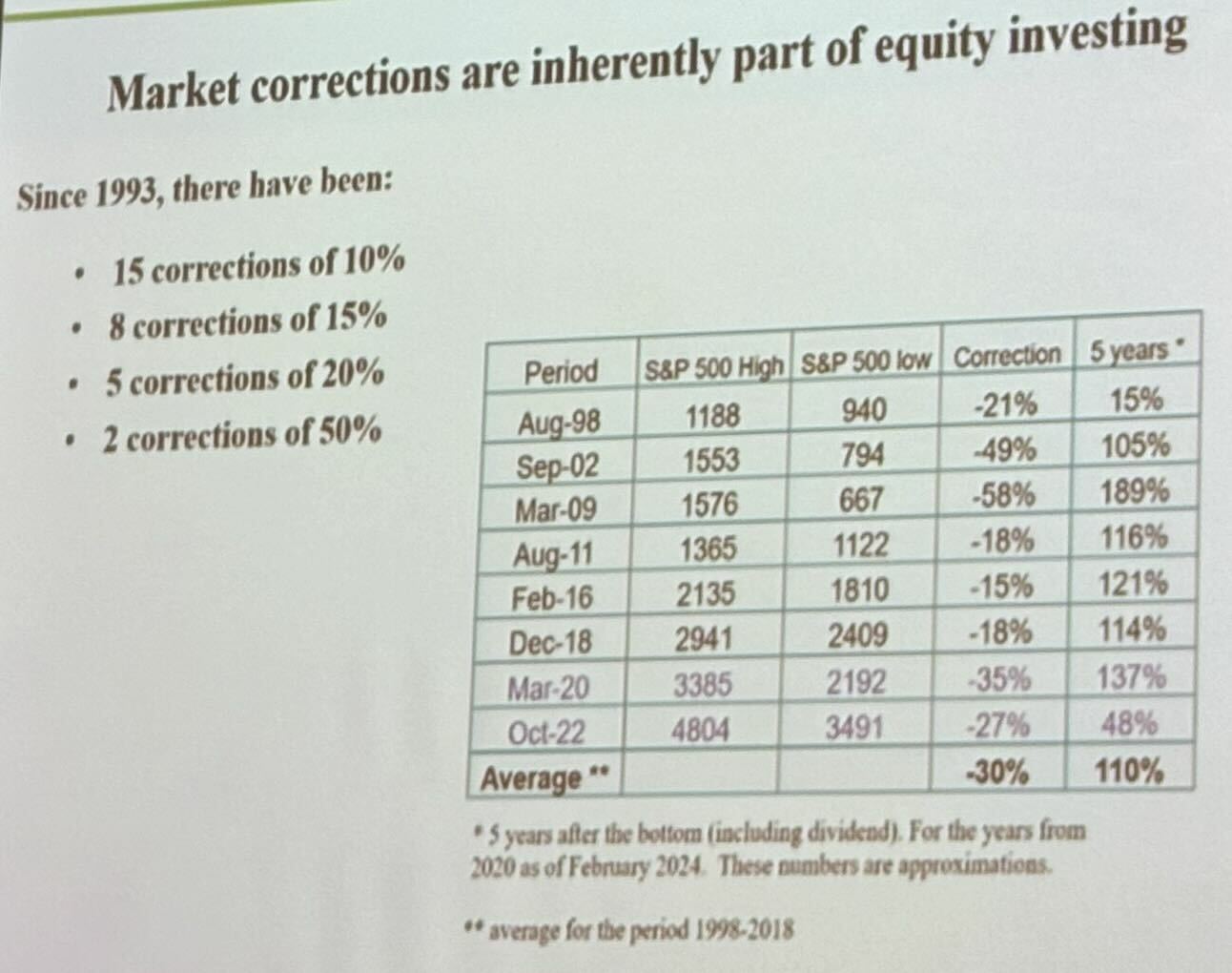

Rationality is basically keeping a cool head during crashes and manias. There are many charts similar to the following one, but it sill amazes me how often markets go down and how much they ultimate go up in the longer term.

Essentially, since 1993, an average market correction was 30% and 5-year performance after that was 110%, on average. A 10% correction happens once every two years (so every year, investors face a 50% chance of losing 10% if they invest in the broad market index).

Dramatic declines of 50% happened twice in the past 30 years - around 7% probability, not something that can be completely ignored, but equally not the reason to stay fearful and avoid investing in stocks.

My favourite part was on Patience. I have come to the same conclusion, and I see many investors still making the same mistake I made more often in the past.

Dramatic declines of 50% happened twice in the past 30 years - around 7% probability, not something that can be completely ignored, but equally not the reason to stay fearful and avoid investing in stocks.

My favourite part was on Patience. I have come to the same conclusion, and I see many investors still making the same mistake I made more often in the past.

"Holding on to a company that is reporting bad results or going through serious troubles is not patience. It is denial.”

- Francois Rochon

I know that buying a great business during a temporary hick-up is a good strategy. But I think more money has been lost when investors did not take the first signs of trouble too seriously.

Patience is needed when you hold a great business that takes time to fully reach its potential, and the stock may lag the company's underlying performance. It is similar to a gardener who patiently looks after his plants and watches them grow and blossom over many years and decades.

Patience is needed when you hold a great business that takes time to fully reach its potential, and the stock may lag the company's underlying performance. It is similar to a gardener who patiently looks after his plants and watches them grow and blossom over many years and decades.

We don't try to time the stock market. We expect to be fully invested in most environments. Stocks outperform other asset classes over time.

- Francois Rochon

Sell guidelines

This topic has been well discussed by other investors, but it is always great to remind ourselves the following four points:

The first point is the hardest to follow, especially for those who make their views public. The second point requires making an important distuingish between short-term issues and serious problems with long-term consequences.

As for ‘overvaluaiton’, it is the hardest in my view. Costco, for example, looked expensive so many times over so many years, but selling it 10 or 5 years was still a mistake judging by the consequent performance.

The last one is probably the easiest to follow but is rarely practised. Quite often we look at each investment on a stand-alone basis, but things look much more obvious if we compare a new idea with the stocks in the current portfolio. The moment I find ‘dreams’ in my portfolio (macro would improve, the company could raise the dividend, the market will start appreciating the defence nature of this business), I know I have to start ‘cleaning the house’.

- We made a mistake in our analysis

- The business fundamentals of the company deteriorate of new developments and analysis invalidate the original investment thesis

- The stock is clearly overvalued

- A new opportunity is significantly more attractive than an existing holding

The first point is the hardest to follow, especially for those who make their views public. The second point requires making an important distuingish between short-term issues and serious problems with long-term consequences.

As for ‘overvaluaiton’, it is the hardest in my view. Costco, for example, looked expensive so many times over so many years, but selling it 10 or 5 years was still a mistake judging by the consequent performance.

The last one is probably the easiest to follow but is rarely practised. Quite often we look at each investment on a stand-alone basis, but things look much more obvious if we compare a new idea with the stocks in the current portfolio. The moment I find ‘dreams’ in my portfolio (macro would improve, the company could raise the dividend, the market will start appreciating the defence nature of this business), I know I have to start ‘cleaning the house’.

The three most important lessons learned over 30 years:

- Never try to predict the stock market and always keep a long-term horizon. Act like an authentic owner!

- The key is to own outstanding companies over many years. Valuation is important but it should not be the first criteria.

- Develop and strive to improve on the right behaviours: Rationality, Humility and Patience.

In many ways, the story of Francois Rochon is similar to Charlie Munger, who put the quality of the business and returns on capital over the long term over valuation.

The books that inspired Francois:

Two stock ideas

Francois Rochon briefly spoke about two of his top ideas.

The first one was Constellation Software. According to Rochon, it is a great business with a stable and recurring revenues and ownership of many ‘niche’ companies. It is a consolidator in a very fragmented industry. It has a strong balance sheet and owner-oriented CEO.

Hard to believe, but the stock was trading at 15x P/E at some point in 2014m, when Giverny Capital first bought it. He admits it is much more expensive now, but he thinks it still worth adding during market corrections when the stocks gets cheaper.

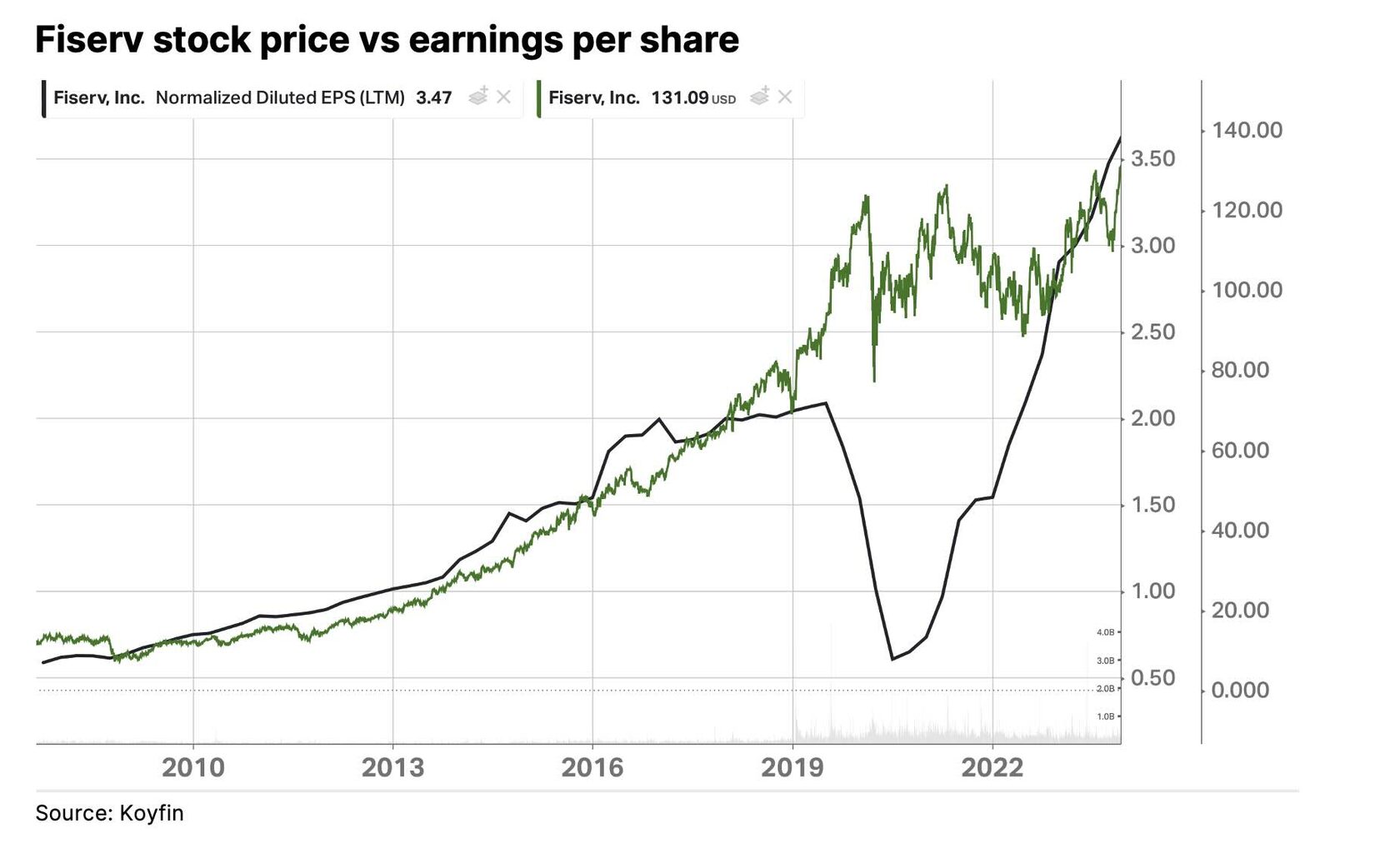

The second idea was the stock they bought in 2023. It is a payment business, Fiserv, which was also trading at 15x last year.

The first one was Constellation Software. According to Rochon, it is a great business with a stable and recurring revenues and ownership of many ‘niche’ companies. It is a consolidator in a very fragmented industry. It has a strong balance sheet and owner-oriented CEO.

Hard to believe, but the stock was trading at 15x P/E at some point in 2014m, when Giverny Capital first bought it. He admits it is much more expensive now, but he thinks it still worth adding during market corrections when the stocks gets cheaper.

The second idea was the stock they bought in 2023. It is a payment business, Fiserv, which was also trading at 15x last year.

Rochon briefly mentioned strong management, a hard-to-displace business with stable and recurring revenues and a strong inflation hedge.

Payments is the sector I know very little about. There are many players and a high pace of innovation. This has always made me feel that I will struggle to get an edge. So, I usually pass on the opportunities in this sector.

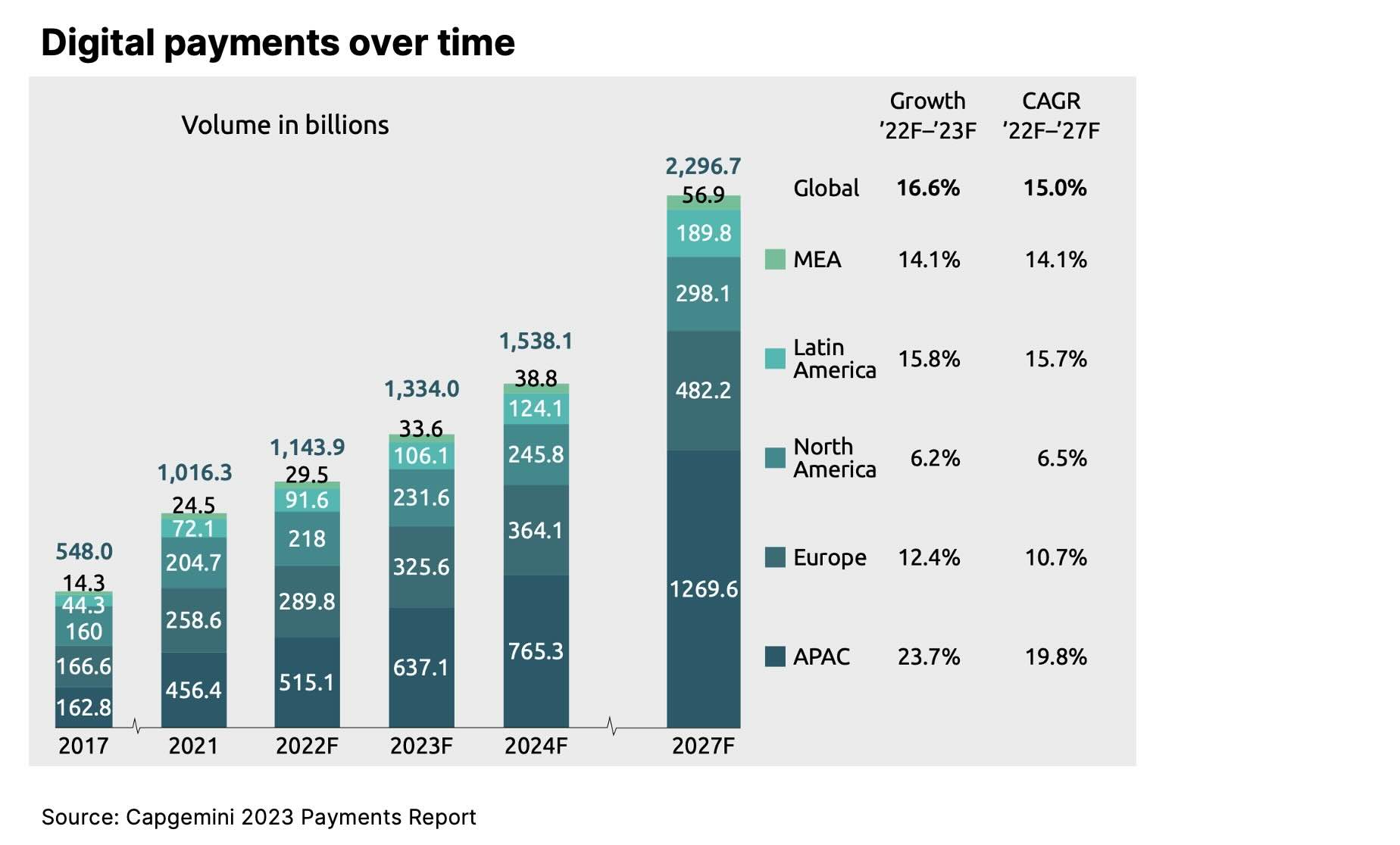

On the other hand, a payment business provides a critical role for the customer at a fairly low price (e.g. 1% of transaction value or less). It naturally grows with inflation and benefits from the rise of online and digital payments, which continue to substitute cash. The payments industry is huge (measured in trillions of dollars) and is still fragmented, with many new verticals available for consolidation.

There are also strong tailwinds for the industry, as it has been growing well ahead of GDP at 10-15% a year and is expected to maintain this growth in the 2020s. The reason is that more transactions are going online or digital, and the nature of the economy is changing with the rise of the gig economy, entertainment, gaming, and many other sectors that require more frequent transactions, often international.

Payments is the sector I know very little about. There are many players and a high pace of innovation. This has always made me feel that I will struggle to get an edge. So, I usually pass on the opportunities in this sector.

On the other hand, a payment business provides a critical role for the customer at a fairly low price (e.g. 1% of transaction value or less). It naturally grows with inflation and benefits from the rise of online and digital payments, which continue to substitute cash. The payments industry is huge (measured in trillions of dollars) and is still fragmented, with many new verticals available for consolidation.

There are also strong tailwinds for the industry, as it has been growing well ahead of GDP at 10-15% a year and is expected to maintain this growth in the 2020s. The reason is that more transactions are going online or digital, and the nature of the economy is changing with the rise of the gig economy, entertainment, gaming, and many other sectors that require more frequent transactions, often international.

The payment providers do not require much capital, benefit from network effects and economies of scale and consequently earn high margins and returns on capital.

So, I decided to look in more detail at Fiserv. You can find my overview of the company, its valuation and conclusion here.

So, I decided to look in more detail at Fiserv. You can find my overview of the company, its valuation and conclusion here.