Everyone has a plan until they get punched in the mouth.

- Mike Tyson

Summary

The stock has declined 30% since I published my original thesis. Despite this, I believe that it still offers a reasonable upside. I am confident in my overall thesis that Alibaba continues to be a leading e-commerce platform in China that is not going away, and neither does the government aim to ‘destroy’ it.

However, the evolution of the Chinese consumer market, rising competition and stricter regulation put pressure on Alibaba’s profitability. A recent economic slowdown is another temporary factor behind declining growth rates and margins.

Having done additional due diligence and listened to the latest earnings call and Investor Day, I have reduced my estimate of the intrinsic value of Alibaba by 22% to around $205/ADS (using a probability-weighted approach).

I have decided to keep my current position and not add on further weaknesses because 1) I still have a decent position size (c. 5.5%); 2) I see new interesting opportunities emerging which could potentially be more attractive than Alibaba at the moment.

What has changed since I published my original thesis

The stock has declined 33% in just two months since I posted my original post on 24 October 2021. A few developments have taken place during that time:

- Alibaba reported weaker-than-expected 2Q22 financial results and reduced its FY-22 revenue guidance to 20-23% growth from 30% previously. The new guidance implies 14% revenue growth in 2H22 compared to actual growth of 31.6% in 1H21;

- The company hosted its Annual Investor Day;

- Alibaba changed its management structure, giving more power to heads of key business units and announcing the replacement of its long-standing CFO, Maggie Wu, with her deputy, Toby Xu (from 1 April 2022);

- Alibaba reported $85.5bn GMV during its 11-day Singles Day event, an increase of 8.5% YoY compared to 26% YoY growth in 2020. The growth rate looks reasonable considering the high base effect of last year and the less aggressive promotion of the event this year, in line with the new state policy. However, it is pretty worrying that JD.com has delivered much higher growth in GMV this year (+28.6% YoY) with sales of $54.6bn. JD.com also reported more robust GMV growth during 2020 Singles Day (+33%);

- SEC established a framework for implementing the law introduced in 2020. According to that law, foreign companies can be delisted from US exchanges if they fail to provide the information requested by the US regulator, which oversees the audits of public companies. DiDi, the leading ride-hailing company in China, announced plans to delist its shares from the US and list them in Hong Kong;

- I have also made a series of personal observations, which I will share later in this post.

I have two key conclusions.

Firstly, Alibaba remains a solid business and is not going away or being ‘destroyed’ by the government. The company continues to deliver decent growth despite temporary issues. It maintains a long-term focus by increasing investments into the quality of its services, putting its short-term earnings at risk. Besides, the Chinese government has recently introduced stricter measures across different sectors, confirming my original assumptions that the government did not single out Alibaba in its crackdown measures.

My second conclusion is that Alibaba’s earnings will remain under pressure for some time (probably 1-2 years) as the company needs to invest more into the quality of its service in light of competitive pressures as well as due to regulatory changes (particularly new competition law and use of personal data).

Alibaba's earnings power is weaker in the near-term

I think Alibaba's earnings are negatively affected by two key issues: lower 'Take Rate' and higher Marketing expenses (Customer Acquisition Costs or 'CAC').

In the past, platform companies were able ‘to lock in’ merchants by forcing them to work on just one marketplace. Consumers were also not able to communicate across different platforms. Now, when merchants can work at several platforms at once, and consumers are better informed, key e-commerce players will not be able to raise their commissions (‘Take Rate’) as they risk losing merchants to a competing website. They will also have to increase marketing expenses to keep consumers on their platforms (Customer Acquisition Costs, CAC, will be rising).

Take Rate

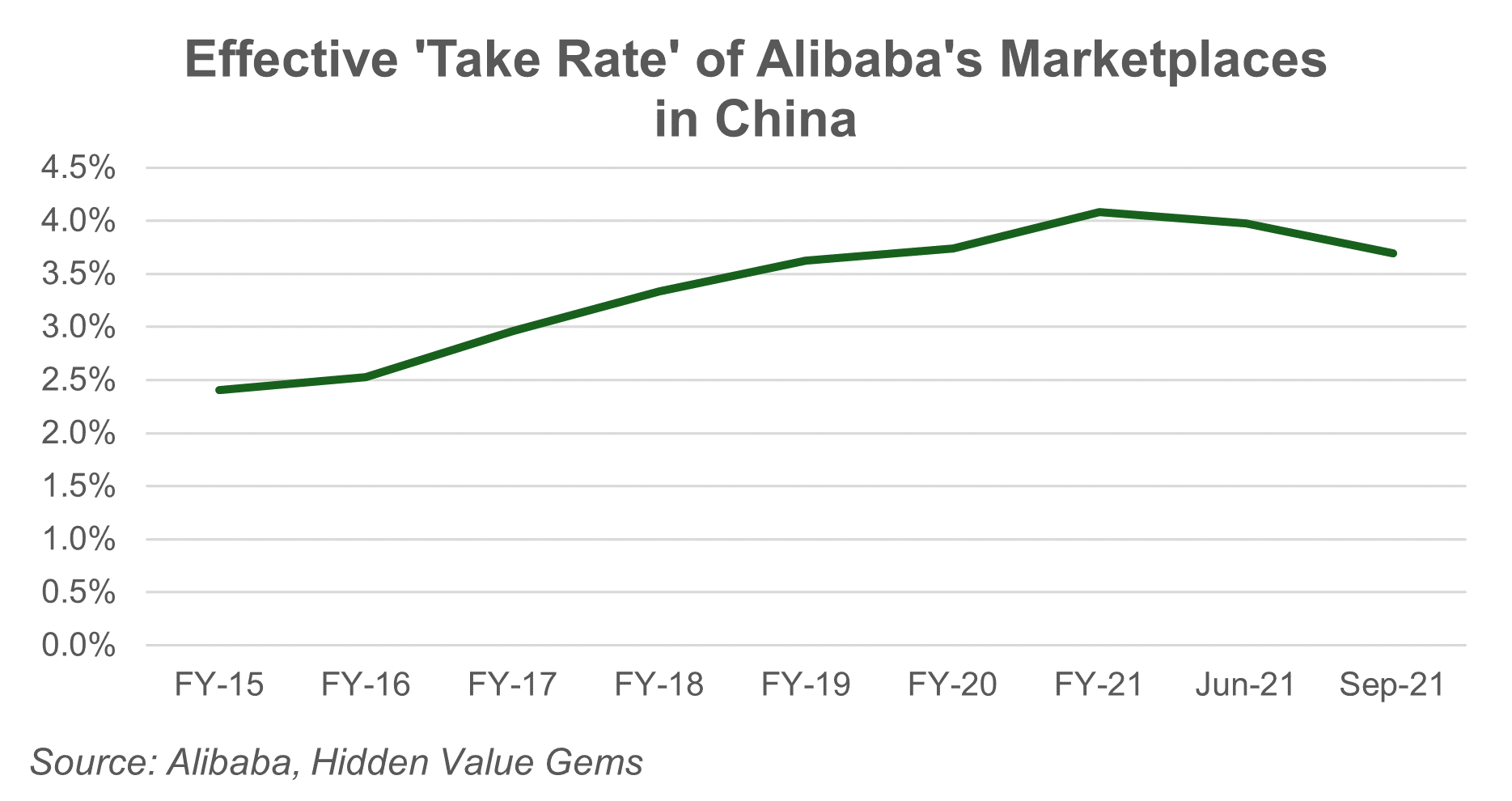

Alibaba’s effective Take Rate (which I estimate as Customer Management & Commission Fees relative to GMV) has gradually increased since FY-15 from 2.4% to 4.1% in FY-21. However, it has started to decline this year to 4.0% in 1Q22 and 3.7% in 2Q22. I think this reflects regulatory pressure, rising competition and economic slowdown. I do not believe this is a new long-term trend of falling Take Rate, but it will take some time to reverse, probably 1-3 years.

Customer Acquisition Costs (CAC)

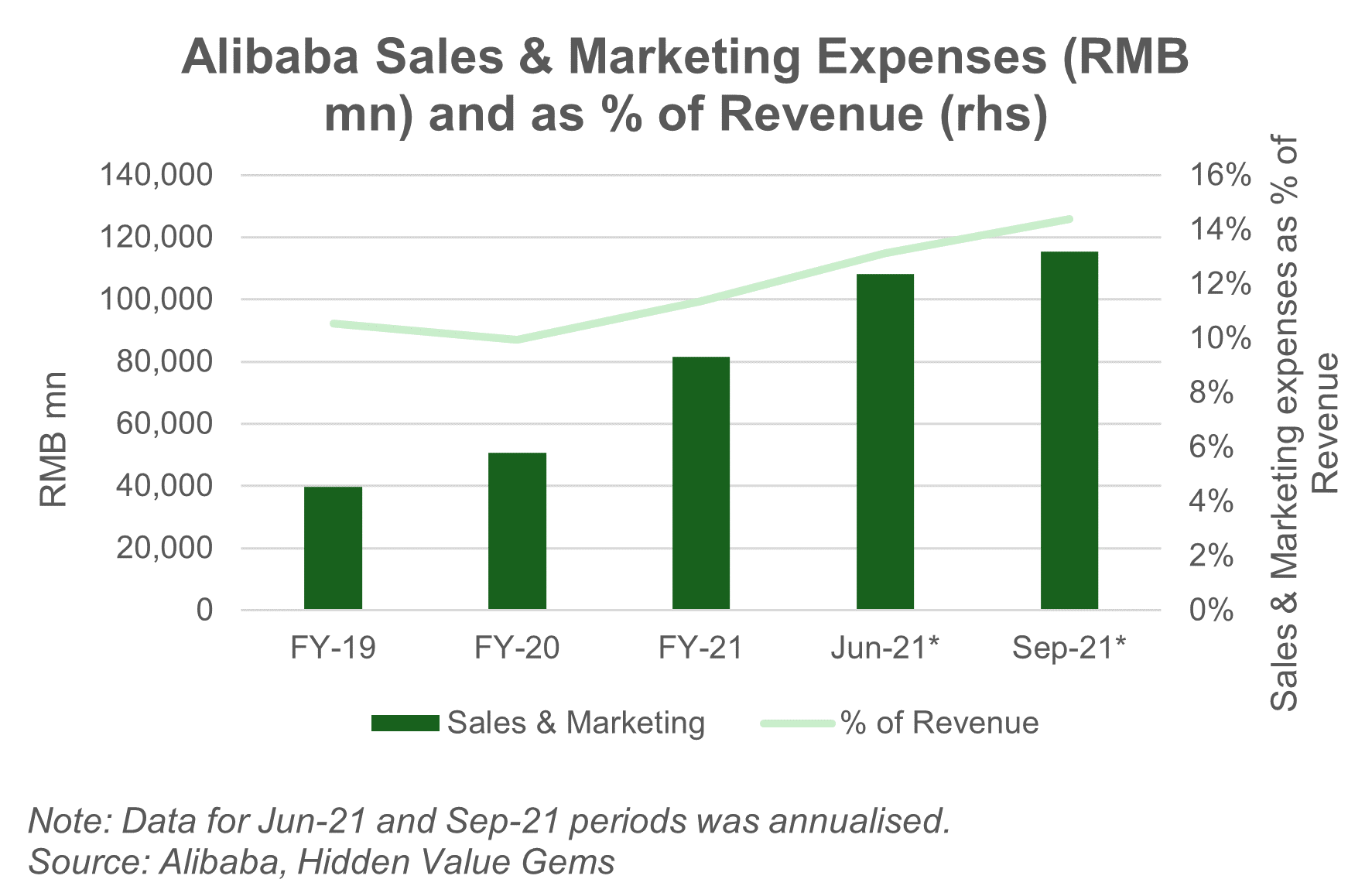

Equally negative is the trend of rising Marketing expenses as Alibaba faces stronger competition from new players. Its Marketing expenses averaged 10-11% of Sales during the FY19-21 period but has started to rise this year to 13% in 1Q22 and 14% in 2Q22.

Like Take Rate, I think Marketing expenses should fall relative to sales due to scale effect and new ventures mature. However, this will likely require some time, at least a year.

Earnings should remain under pressure because Alibaba is also actively expanding into more remote regions targeting low-income populations. Selling goods to that category of consumers (with low Average Order Value (AOV) and potentially higher delivery costs due to less developed logistics infrastructure) would impact returns negatively.

It is also important to note that with the customer base reaching 1bn people in China by March 2022 (per the management target), Alibaba’s future growth potential remains relatively limited. I think it may be a little misleading to look at past growth rates and expect the market to pay a growth multiple for current earnings, given declining growth potential.

Cloud, International commerce, Digital Media and other products will likely contribute to future growth, but the tailwind will not be as strong as previously. Note that China’s GDP was growing at almost twice the rate ten years ago, and the share of e-commerce was increasing from zero to nearly 30% currently.

This chart on the market shares of key e-commerce players in China is quite telling. Alibaba remains the leader for now (59% market share in 9M21, down from 65% in 2016), but maintaining this position is becoming more expensive now. There is no reason to panic, but important consideration for adjusting mid-term expectations on growth and margins.

The revised estimate of intrinsic value

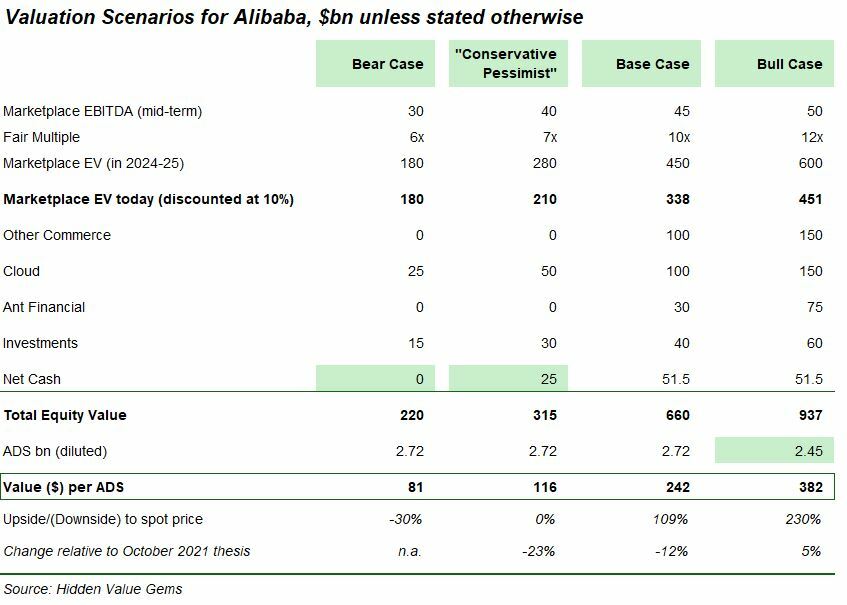

Intrinsic value is never a single number that can be estimated precisely. My range of estimates for Alibaba is quite broad: between $382 in the Bull Case and $81 in the Bear Case, with an average of $205 for four scenarios.

I continue to use a Sum-of-the-Parts (SOTP) valuation method, but this time I add one more scenario to the original three scenarios. I call the previous Bear Case “Conservative Pessimist” and add a new Bear Case with more negative assumptions.

The new Bear Case

I use the latest 12-month EBITDA of Alibaba, which includes earnings from the core Marketplace business and losses from most other segments, including New Retail, International Commerce, Media Entertainment and Innovation Initiatives. Essentially, I assume that these losses will remain indefinitely and are a necessary ‘cost’ of doing business in China.

I apply a very conservative EV/EBITDA multiple of 6x (for comparison, Amazon is trading at 27.5x EV/EBITDA). Such conservative multiple assumes no real growth in the future. I arrive at a $180bn value for the core business ($66/ADS).

Such low multiple reflects my expectations of weaker EBITDA in the next 12-18 months as Alibaba continues to invest more aggressively in new services

Outside of the core retail business of Alibaba, I only include Cloud and Investments, both highly discounted. At the same time, I assume zero value to Ant Financial and Cash position (as if the company loses Ant Financial completely and burns its current $51.5bn net cash on social projects, for example).

Alibaba’s Investments are worth c. $38.3bn based on the latest Balance Sheet data (which is marked to market), and I apply a 60% discount to that. Valuation of Cloud business ($25bn) implies 2x EV/Revenue multiple (based on the annualised revenue of the last quarter), while peer Cloud companies trade at 10-30x EV/Sales multiples.

“Conservative Pessimist”

The second scenario is slightly more optimistic than the new Bear Case. Here, I assume that extra investments in new retail formats (Other Commerce) still do not generate any value, but at least they do not ‘destroy’ the value of the core business. I assume better profitability for the Marketplace in the medium-term ($40bn of EBITDA compared to $30bn in the Bear Case) and apply a marginally higher valuation multiple for the Marketplace (7x).

Importantly, I introduce a time factor in all scenarios except the Bear Case to reflect the time required to achieve these improvements (and the consequent opportunity cost). I assume that it would take about three years to reach a specific EBITDA level ($40bn in this case). As a result, I discount the value by three years using a 10% discount rate.

I arrive at a $210bn valuation for the Marketplace ($77/ADS) and still assume zero value for Other Commerce.

I take a slightly more optimistic view on the value of Cloud ($50bn or $18/ADS) and Investments ($30bn or $11/ADS). My valuation of Cloud assumes a 4x EV/Sale multiple based on the past quarterly revenue. The multiple is considerably lower if applied to future sales estimates since the Cloud segment has grown at a 90% 7-year CAGR.

Finally, I assume that ‘only’ half of the current cash pile will be burnt and include the remainder ($25bn or $9/ADS) in my valuation.

My final estimate of Alibaba’s intrinsic value is $315bn ($116/ADS), close to the spot price and 23% below the value of the previous Bear Case (published in October 2021).

In a way, this scenario may be the closest to what the market is currently thinking about Alibaba: a complete ‘car-crash’ scenario is avoided, but all valuation multiples and critical assets are heavily discounted due to increased political risks. Remember, you do not pay anything for Ant Financial in this scenario. It was valued at about $300bn ahead of IPO ($100bn net to Alibaba or $37/ADS).

Base Case

My Base Case for Alibaba reflects assumptions that look the most realistic to me.

I assume that the Marketplace starts generating $45bn of EBITDA on a sustainable basis and does not require heavy investments in other segments, resulting in losses. To remind, over the past 12 months, Marketplace EBITA (before Depreciation) amounted to RMB232.1bn or about $36bn. If we add back an estimated Depreciation charge of c. $3bn for the segment, we get $39bn of EBITDA earned over the past 12 months.

I also use a higher valuation multiple of 10x, which I find adequate for a high-return business close to saturation. I arrive at a $450bn value for the Marketplace, which I further discount to reflect the time value of money, which gets me to $338bn ($124/ADS).

In other words, if my assumptions in the Base Case are correct, you only pay for the value of the company’s Marketplace and receive all other businesses and net cash for free. On my estimates, this ‘free’ stuff amounts to $321.5bn ($118/ADS).

One can debate how much other businesses are worth, and even I am wrong, the upside is still considerable (easily 50% from the current spot price).

For this upside to materialise, Alibaba should prove that its efforts are paying off. To me, that means that the company transforms its business model from a pure intermediary role by connecting merchants with prospective buyers to a more value-add service with more flexible and faster delivery options, a more comprehensive range of product categories, higher quality of products offered and other auxiliary services.

Of course, the regulator should also be satisfied with the company’s efforts and not issue new penalties constantly or force it to increase costs in other ways (e.g. raising the minimum wage for employees).

This scenario also assumes that Alibaba successfully fends off competition and maintains its c. 20% market share in the Chinese retail sector.

The difference between the market and my views on Alibaba is that I think a few of the recent issues are temporary (e.g. economic slowdown in China, regulatory pressure and consequent adjustments), and the company is in a position to address the other problems (mainly around competition). The latter point is based on its track record, long-term focus, and strong innovative culture.

Bull Case

Given that I get over 100% upside even in the Base Case, there is little point in looking at the Bull Case scenario.

For reference, my Bull Case valuation is $937bn for the whole of Alibaba ($382/ADS), which is 23.5% above the company’s all-time high price ($309.92) reached on 23 October 2020. It is 5% higher than my previous assessment made in October this year. The main reason is that I now use a lower share count as the company has launched a $15bn buyback programme purchasing 26.9mn of ADSs for $5.2bn from July through September 2021. I assume that the company will continue to proactively buy back its discounted shares, reducing the share count by 10% to 2.45bn ADSs.

I am convinced that no assumption is too optimistic in this scenario, as long as the company maintains its leading value proposition for consumers and merchants and continues developing new businesses as it has successfully done.

I plan to discuss critical assumptions in greater detail if and when the share price rallies to above $200, approaching my Base Case valuation, which will force me to consider trimming or holding the stock depending on my views.

Additional thoughts and data points

Personal experience

I have purchased a kids watch for my daughter at AliExpress for the first time. After using Amazon for over ten years, I was quite disappointed by the overall experience. Apart from less attractive design (this could be subjective), choosing a product and ordering / paying for it was quite complicated. Moreover, I got the impression that the price changed if I started to look for the same product again. Partially it could have been due to different currencies. At some point, I saw prices in USD, later in GBP, even though the website knew my location. Many discounts are offered, especially for first-time buyers, but they are not straightforward and clear.

The good thing was that prices were generally lower than at Amazon but at the expense of longer delivery (about three weeks vs one day for specific models at Amazon and up to a week for almost all types of kids' watches).

To finish with my disappointing customer experience, I should note that I now receive about three emails from AliExpress every week with different promotions. I am aware that they try to offer me products that may be relevant to my profile, including based on my search and other activity over the internet. And because of that, I was even more surprised to receive once an email with the following offers:

In addition to the usual promotion of Menswear, the email had a section on Women’s wigs with ten different options and prices from $46 to $135 (as I have never been interested in wigs, I cannot decide how attractive the offer was, maybe it was a bargain in the end).

Luckily, I have only received this email once, and it could be that there was some bug in the algorithm. Still, you would not expect this from the world’s leading e-commerce platform.

A new book on Alibaba

As part of my due diligence on the company, I have decided to read another book (in addition to ‘The House That Jack Ma Built’, which I reviewed HERE). This time it was ‘Smart Business’ by Ming Zeng. The second part of the title was quite promising (‘What Alibaba’s Success Reveals about the Future of Success’). Moreover, the author was a Chief Strategy Officer at Alibaba and a professor at INSEAD.

I was quite shocked by how simple the content of the book was. The central message that Alibaba is not a traditional company, but an eco-system was repeated in different contexts dozens of times in the book. The author also highlighted two key drivers of the company’s strategy: Network coordination and Data intelligence.

I found the content relatively shallow, something that I would expect to find on a free internet library by a little known blogger.

I do not think this is necessarily bad for Alibaba’s investment case. It could be that the author was just unlucky with the book or was deliberately evasive in the details. But I also think that the company’s success lies in relentless execution and a culture full of energy, enthusiasm and innovation.

It is quite challenging for an academic to express the strategy of a company founded in a small flat with little capital but tremendous vision and determination.

In a way, I am optimistic about Alibaba because if there was a secret formula or algorithm that catapulted it to the top ranks, at some point, competitors could have discovered this code and replicated it. It is much harder to replicate team culture, innovative spirit, collaboration and ambitions.

Aikya: a thesis explaining why they passed on Alibaba

I came across quite an interesting piece by a fund manager (Aikya), written in winter 2020.

I agree that most points are relevant and raise some concerns. However, they can also be applied to many other companies. For example, the VIE ownership structure is the only option for Chinese companies to be listed in the US. A high level of investment is the ultimate source of innovation and creating new businesses like Alibaba Cloud, for example. There is a valid concern about the role of the government, and the jury is out there on how well Alibaba can now address the issue. My counterargument is that Alibaba is so dominant in China today that even if it benefited from the government’s support previously, it does not need it. And I do not think the government’s goal is to ‘destroy’ the company but rather to level up the playing field (which will impact the company’s profitability and has been reflected mainly in the share price, in my view).

I also do not entirely agree on the issue of ‘Quality of Financials’. Firstly, I do not value the company on a PE basis, and secondly and more importantly, the company has been generating positive FCF and building a net cash pile. If the company had generated only ‘paper’ earnings, it would not be able to earn positive FCF and accumulate cash.

The most crucial point is that even with several concerns, Aikya estimates that the company could be generating c. $60bn of FCF in 2030. The fund manager values this FCF at a 5% yield implying a valuation of $1.2tn (in 2030). They make a fair comment that such valuation adjusted for share-based compensation dilution would allow them to earn only a 3% annual return. This return estimate was made on 31 December 2020, when Alibaba’s stock closed at $232.73.

Surely, at $119, the upside has become more attractive.

Aikya also noted that this valuation is relevant only if two of its concerns are addressed: ‘stewardship’ (VIE structure, capital allocation, corporate governance) and financial quality.

Tencent plans to sell its stake in JD.com

I think this decision is partially driven by Tencent’s proactive steps to create value, as the value of its numerous investments is not fully reflected in Tencent’s share price. By distributing the shares in JD.com, management undertakes a step to reduce the discount.

However, I also think that Tencent probably sees less upside in JD.com than in its other investments. You do not start selling your most undervalued position first. It is a slightly negative signal for Alibaba. Worth keeping in mind the next time Alibaba’s shares rally, which may create a temptation to buy more.

Further risks and considerations

What would lead me to change my view

In investing, you deal with uncertainty and probabilities. Monitoring how probabilities change after investing is as important as the original thesis. Below I have summarised the factors that I am watching. Depending on the signals and the share price/valuation, I could either sell my position or increase it.

The negative signals that I am focusing on are as follows:

- Regulatory changes that single out Alibaba alone

- Poor corporate governance, related-party transactions at the expense of minority shareholders

- Competition, material improvement of key players, Alibaba losing market share by 10p.p.

The positive signals include:

- Acceleration of GMV to above double-digit rate

- Stabilisation of Take rate (and gradual recovery)

- Stabilisation of Marketing expenses as % of Sales

- Other business: progress towards breakeven (declining losses relative to sales)

Stating your opinion publicly

In a few books that I have read recently about decision-making, I found that an opinion stated publicly is harder to change, so we are more prone to follow poor judgment if we are very vocal about our original decision. This has to do with a fear of looking wrong and incompetent.

I keep this in mind with my thesis on Alibaba and ask myself if I would act differently had I not written about my initial thesis before? Is there a risk that I try to convince myself why it is an attractive opportunity just because I do not want to admit the previous mistake?

Other potential risks

I think holders of Alibaba (including myself) should be aware of low-probability but high-impact risks, such as military conflict around Taiwan and material escalation in trade and sanctions wars between US and China.

It is essential to keep this in mind as the stock may drop significantly if such events unfold, but they are beyond one’s control and will likely be long-lasting. This is more of a warning (including to myself) not to be tempted to sell if the stock drops another 50% on the back of an open conflict.

I am not an expert on this subject but using a general judgement, I believe that the probability of such a scenario is relatively low to use it as a reason to sell Alibaba’s stock now.

There is also a risk of delisting shares from the US stock exchange. Fundamentally, this should not affect the value of Alibaba, which equals the sum of all future cash flows discounted to today. But such an event can cause additional volatility as some investors would not be able to hold non-US listed shares in Alibaba. The quality of disclosure may also change if Alibaba is not listed in the US. I do not think that chances for delisting are significant (less than 20%) as international listings benefit US as a global financial centre and in a way help the Chinese government promote its 'national champions' abroad.

Possible mistakes and lessons learned (so far)

1. Position size

In hindsight, I should have started with a lower position and added more slowly as I did more research. As part of my due diligence, I should have done more product testing (ordering on AliExpress).

I was open about my little edge in the situation (especially knowledge of the local market) but acted as if I knew more about it.

2. Market competition problem takes longer to be resolved

In Alibaba’s case, it was evident that the company suffered not just from a regulatory clampdown but also faced more vigorous competition in the core market. The latter cannot be fixed quickly and usually takes at least a year, and occasionally can never be resolved. I am convinced that Alibaba’s scale and focus would help it maintain its market position, but it may take time. So better to buy gradually.

3. Range of real-life outcomes usually is wider than we think

This idea has been often discussed in various books on Behavioural finance and judgement, but I still made the mistake of focusing on a pretty narrow range of potential outcomes. My original ‘Bear Case’ was not ‘bearish’ enough. I also was under some influence from past trends, extrapolating them into the future. This is typical for humans to miss inflexion points using linear thinking. I should have put past growth rates into the context of faster Chinese growth and early-stage penetration of e-commerce – both of these factors will not be repeated going forward.

4. Circle of competence

This case serves as a good reminder of the importance of staying within your circle of competence. As Buffett likes to explain, his success did not come from his exceptional IQ but from focusing on simple questions and avoiding the hard ones. His partner, Charlie Munger, says that:

We just look for no-brainer decisions. As Buffett and I say over and over again, we don't leap seven-foot fences. Instead, we look for one-foot fences with big rewards on the other side. So we've succeeded by making the world easy for ourselves, not by solving hard problems”.

5. Great Business vs Method

This leaves me with the last point. I try to practice two investment strategies. One focused on finding great compounders and not overpaying for them. Another is using the right method, which on average generates attractive returns, but certain positions can nevertheless be money-losing.

Alibaba is the latter, and as such, it is vital to start with a lower initial weight and not judge the method by the single outcome.

DISCLAIMER: This publication is not investment advice. The primary purpose of this publication is to keep track of my thought process to assess future information better and improve my decision-making process. Readers should do their own research before making decisions. Information provided here may have become outdated by the time you read it. All content in this document is subject to the copyright of Hidden Value Gems. The author held a position in the stock discussed above at the time of writing. Please read the full version of the Disclaimer here.